Guwahati, Assam: June 4, 2023, was a typical, searing summer’s evening in Bihar’s Bhagalpur. There was the usual hubbub at the Namami Gange Ghat in Sultanganj town of the district. Nearby, the Aguwani-Sultanganj bridge was under construction.

Ajit Kumar, a local activist and first-time candidate in the Assembly polls, was at his house near the ghat, watching as his car was being washed. Suddenly, a deep, echoing bang split the evening. “It felt like there was loud thundering from the sky,” he said. “I looked up, but the sky was clear. I saw the bridge droop a little. I ran up to the terrace and saw it collapse slowly.” As the falling structure hit the Ganga, people close to the ghat began running for safety. Kumar said, “It felt like an earthquake… The mud and debris seemed to cover 5 square kilometres.”

Some 700 kilometres away from the site, the collapsed bridge sent ripples through the political establishment in Assam’s capital city, Guwahati. The ripple effect: The Assam state government set up an inquiry into the under-construction 8.4 km bridge, meant to connect the hectic Pan Bazaar, located at the heart of the city, with the northern end of the town, across the Brahmaputra.

The link between the collapsed bridge in Bihar and the upcoming one in Assam was the company constructing it, SPS Construction India Pvt Ltd.

A team from the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, was asked by the Assam government to review the ongoing construction in Assam, even as the company was issued a notice by the Bihar government.

More than two years later, findings from that review are not to be found in the public domain.

However, The Reporters’ Collective found the company did make a Rs 5 crore donation to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the same financial year.

SPS Construction is not the only company which won government contracts from BJP governments ruling different states in India’s northeast and donated to the party. We found a host of them.

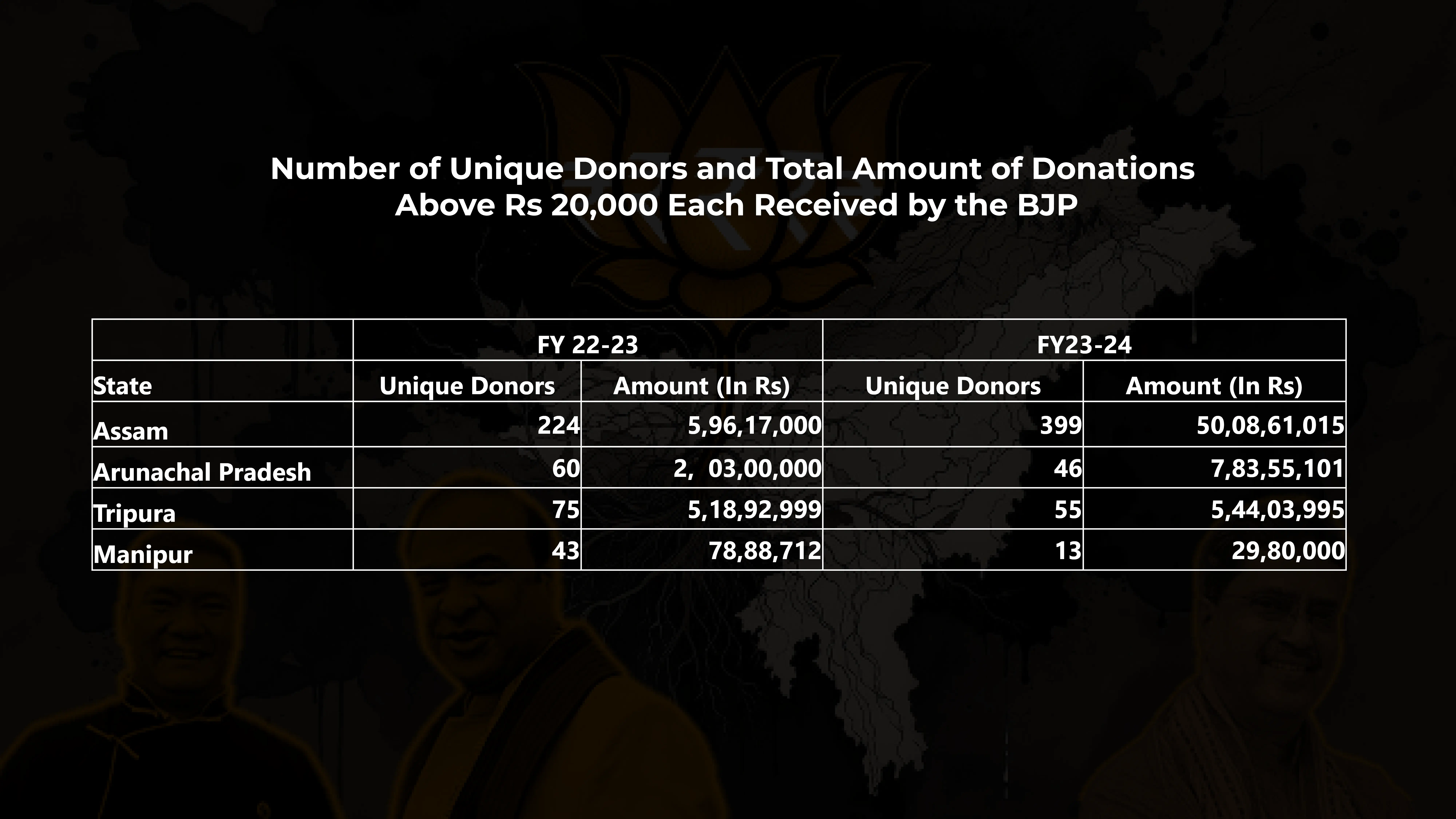

In the two financial years FY 2022-24, the BJP collected Rs 77.63 crore in cheques and electronic transfers from donors in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and Tripura.

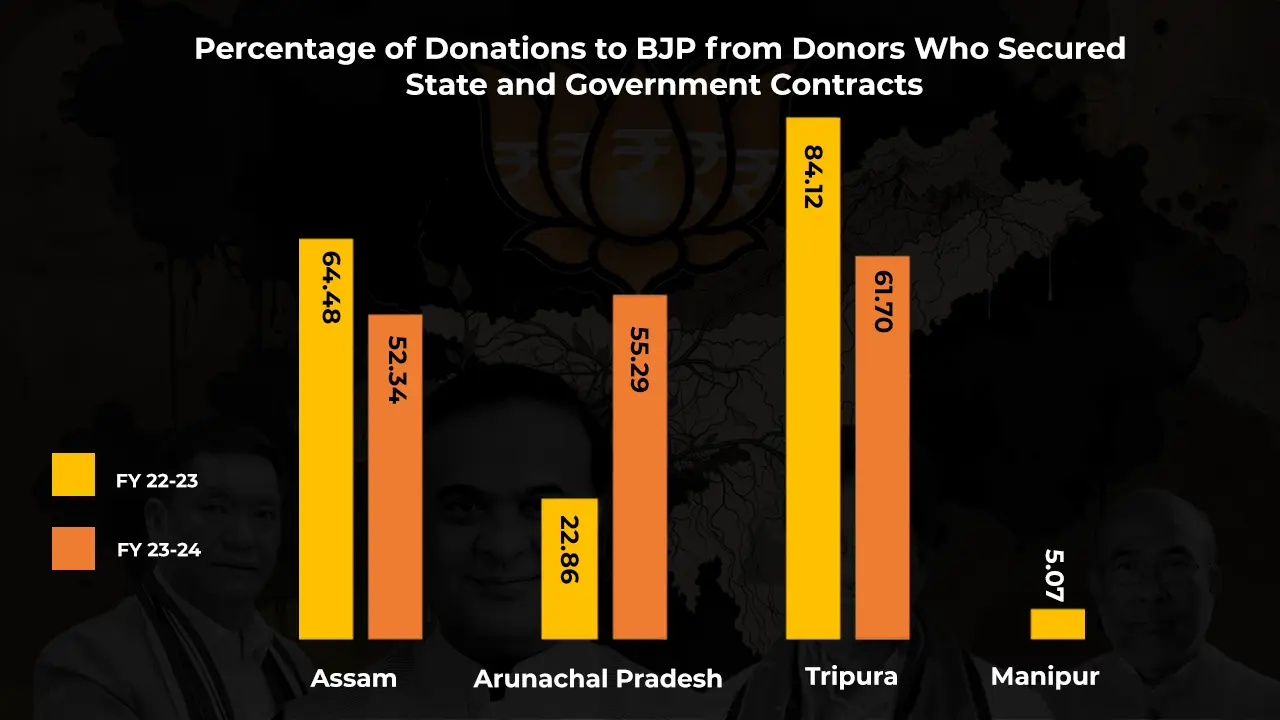

Of this, at least 54.89% came from companies and individuals who had been awarded tenders and secured regulatory clearances by either one of the four state governments or the Union government-controlled agencies.

In Assam, we found that 52.34% of such funds for the BJP in FY 2023-24 were from companies and individuals who had secured government contracts or regulatory clearances. In the previous year, 64.48% of such political donations were made by government contractors.

More than half of the donations above Rs 20,000 that the BJP collected from Arunachal Pradesh in FY 2023-24 also came from those winning state and Union government contracts.

In the same year, over 61.7% of this money that the BJP garnered from Tripura was from government contractors. In the previous year, this number was a whopping 84.12%.

In Manipur, in FY 2022-23, The Reporters’ Collective found that around 5% of the contributions were from companies which had secured government contracts. By May 2023, an armed conflict had broken out in the state. Consequently, the BJP’s formal big-ticket collections fell to Rs. 29.8 lakh in FY 2023-24. We did not find any donations linked to government contractors in that year.

{{cta-block}}

How did we get these details?

Political parties are required to disclose details of donations above Rs 20,000. We analysed the BJP’s donors from the four northeastern states, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and Tripura for the two financial years 2022-23 and 2023-24. ECI is yet to publish details of the BJP’s donors for FY 2024-25.

Through months of investigation, we parsed databases of Union and state governments tenders from past years to draw the linkages between donating individuals and companies, and the contracts they had secured around the time of donation.

This is an exercise to draw the trend of correlation. Not causation.

We were unable to determine the identities of hundreds of BJP donors from the four states because the party did not follow the regulations and hid some of the information in its disclosures to the Election Commission of India. Therefore, this analysis presents conservative figures.

It is not illegal for corporations or individuals doing business with governments to make aboveboard donations to political parties in power. This is a loophole that often raises concerns about how it masks potential crony-capitalism, corruption and quid pro quo arrangements.

The Contractor Economy of India’s Northeast

Concerns about legalised crony-capitalism and secretive funding of political parties peaked when the BJP introduced Electoral Bonds in 2017, which allowed corporates to funnel large sums of unaccounted money through banking channels secretly to political parties. The Supreme Court struck down the bonds scheme in 2024, holding it unconstitutional.

Also, several studies suggest that aboveboard funding of political parties and politicians in India constitutes only a small portion of the total money collected or expended by them.

Niranjan Sahoo, senior fellow with the Observer Research Foundation, who has closely studied electoral funding in India, said: “For all those years till the electoral bonds came about, unknown sources of donation were at 60-70%. It spiked after the electoral bond scheme was brought about; they are now at 62 to 65%, remaining at more than 50%.”

We analysed the disclosure of big-ticket donations from the four states to the BJP through formal and accounted for routes other than Electoral Bonds.

These sums are small compared to political donations that flow from other Indian states to parties. There is a reason to view them as significant when studying political funding from India’s northeastern states.

The region has very low levels of private capital. The state governments and economies depend deeply on funding from the Union government, which gives the party in power at the Centre leverage to a level that it does not hold over other Indian states’ economies. State and Union government contracts for infrastructure, extraction and schemes constitute a dominant part of the region’s economic activity. Businesses from outside the region work closely with regional political elites to corner infrastructure contracts. Call it the contractor-economy of India’s northeast.

Our investigation maps how the contractor-economy of India’s northeast thrives on political patronage. And how the BJP, being the dominant party in power at the Union and regional level, has leveraged this economy to its advantage.

Legal But Bad?

The Representation of the People Act, 1951, requires political parties to declare donations exceeding Rs 20,000 received from any person or company in each financial year. The Election Commission of India enforces this mandate through the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961.

Political parties have to furnish details of the donating person or company, including their names, complete addresses, Permanent Account Numbers, amount of contribution and details of how the donation was made. The ECI makes these details public annually in the form of contribution reports.

From the contribution reports the ECI published in 2022-23 and 2023-24, The Reporters’ Collective culled out details of donors that BJP declared were from Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura and Manipur – the four states in the Northeast region where the party is or has been in power. Manipur has been under President’s rule since February this year.

The names and PAN of the donors were used to look up other information about the donor companies and individuals, including ownership, links to companies (in the case of individual donors) and tenders won by the government. We analysed 1,288 entries containing information about donors for the four states across two years.

Despite the regulations requiring so, complete addresses were not furnished against many of the donors in the contribution reports, which made it challenging to trace and identify hundreds of donors. Their contributions have not been included in our analysis.

We spoke to Bonojit Hussain, a researcher and social activist from Assam on the nature of funding the BJP has been receiving from Assam in particular and other northeastern states in general.

“You will see, in Assam, it’s the business and trading community that is donating to the BJP. These trading communities control the economy. They donated to Congress, too, when it was in power. But it was more discreet and at a lower level,” he said.

By trading communities, he was referring to communities that migrated to Assam from outside the Northeast and hold sway over the markets in many parts of the region. In many states, they also work in partnerships with the regional elite, providing the capital while the latter lends social sanction for a premium.

According to Hussain, however, the disclosed contributions are only part of a larger story in the state. “In Assam, there are syndicates for everything. From the trade of broiler chicken to minerals,” he said. “Politics is [largely] run by syndicate money.”

Our investigation was limited to the ‘official’ donations made aboveboard and does not delve into the assertions Hussain makes. The official donations tell a story in themselves.

In the first part of this series, we revealed how a Ghaziabad-based trust running out of a two-bed room flat had got the BJP government in Tripura to pass a law for it to set up a private university. Around the same time, the trust and its patrons had donated Rs 50 lakhs to BJP.

In the following segment of our report, we delve deeper into some other symptomatic cases of businesses from northeastern states donating to the BJP. We sent questions to all entities named in the story, asking if they accepted that donating to the party in power helped their business. None, except two, replied.

Cosy in Controversy

In 2023-24, companies and individuals linked to the Dhanuka group, based out of Assam, donated Rs 3.35 crore to the BJP. In 2022-23, they had donated Rs 90 lakhs.

In 2022, Ashok Kumar Dhanuka, the scion of the group, found his name embroiled in allegations of funding the BJP’s attempt to buy out MLAs of Congress in Jharkhand and bring down the government in cahoots with the Assam Chief Minister, Himanta Biswas Sarma. There is no public information about what happened in the case.

Dhanuka is a known associate of Sarma. He had succeeded the Chief Minister’s wife, Riniki Bhuyan Sarma, as the Director of Vasistha Realtors, a real estate company.

.webp)

In 2021 and 2022, the Dhanuka family-controlled Ghanshyam Pharmaceuticals company won two tenders from the Union government’s National Health Mission (NHM). An investigation by The Crosscurrent and The Wire had reported that two other group companies had bagged tenders for health-related supplies, bypassing regulations. We emailed queries to Ghanshyam Dhanuka and one involved company. We did not receive a reply from either.

.webp)

Meghalaya-Uttar Pradesh Donor Corridor

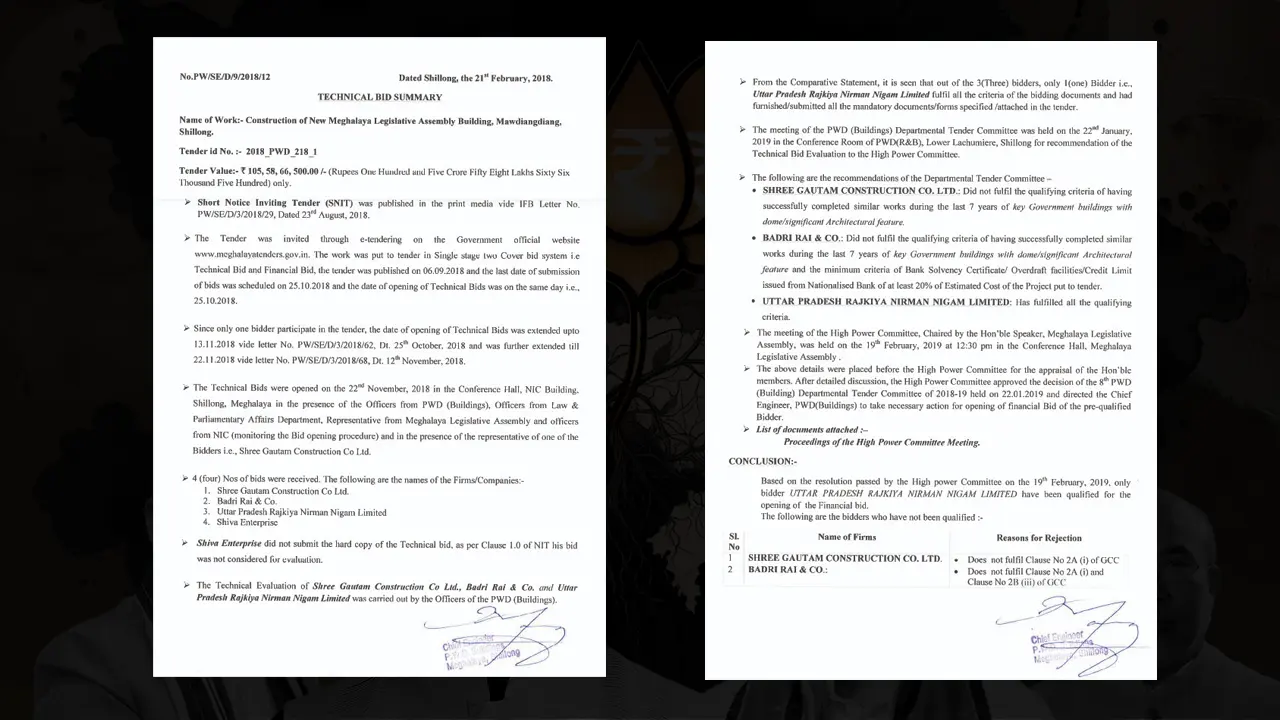

In 2023-24, a construction agency, Badri Rai and Company, donated Rs 1 crore to the BJP.

The company hit controversy when, in 2022, the dome of the under-construction Meghalaya Assembly building in Shillong collapsed, triggering public outrage and political controversy. The National People’s Party is leading the ruling alliance in Meghalaya.

The bid for the assembly building had been won by the Uttar Pradesh government’s Rajkiya Nirman Nigam Ltd by beating Badri Rai and Company. But the UP-government-owned PSU had subcontracted the work to the losing competitor.

.webp)

Badri Rai and Company has undertaken several other infrastructure projects in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya. These include constructing roads, sports stadiums and government buildings. It has won at least 15 contracts for projects in Assam, including the Rs 140 crore contract for the new Assam Police battalion at Birsima in Hailakandi district.

The company did not respond to our queries.

The Arunachal Ally

Samson Borang, a businessman based in East Siang district of Arunachal Pradesh, donated Rs 4.3 cr in 2023-24 to the BJP.

Borang owns Sedi Allied Agency, a contract firm registered with the state’s Public Works Department. Sedi Allied Agency has been awarded three contracts by the state PWD and the National Hydroelectric Power Corporation Limited.

Around 2022, Takar Goi, a lawyer and social activist, asked the state for records and details of contracts being signed by the Arunachal Pradesh government. The case landed before the Guwahati High Court. The judge hearing the matter noted that Goi had sought this information, fearing that the contracts were being awarded in a corrupt manner. Borang’s firm was one of the respondents in the case, suggesting Goi had demanded information on contracts Sedi Allied Agency had won, besides others. We were not able to establish how the case was resolved.

When we reached out to Borang, he said he did not wish to comment on his motivation for donating to the BJP or if he views any link between the donation and the contracts won by his proprietorship.

He, however, claimed the allegations against his firm were motivated by “personal—and not public—interest.”

A Neutral Star?

Star Cement, a cement company headquartered in Meghalaya, donated Rs 5 crore to the BJP in 2023-2024. Previously across three years, it had donated a total of Rs 6.68 crores to the party.

During the Advantage Assam 2.0 business summit held in February this year, the Assam state government and Star Cement signed a memorandum of understanding, inking prospects of a Rs 3,200-crore cement clinker project.

Since 2019, Star Cement has secured at least 18 tenders from the Border Roads Organisation, Indian Oil Corporation Limited, National Hydroelectric Power Corporation Limited, and state government departments for projects located in Assam, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, and Tripura.

We reviewed the company’s annual report for FY 2023-24 to find it had donated Rs 1 crore the same year to All India Trinamool Congress and Rs 1 lakh to Beltola Block Congress Committee.

The Reporters Collective asked the company if it considered a connection between the donation and the contract awards.

In response, the company said, “All contributions made by our Company to political parties are undertaken strictly in accordance with statutory provisions, after obtaining requisite approvals. These contributions are fully disclosed in our Annual Reports, which are publicly available for inspection. Our Company does not discriminate among political parties and has made contributions to major national political parties, as is clearly reflected in our disclosures.”

The company took on a threatening tone, to add, “Refrain from publishing, circulating or disseminating any information relating to our Company without first verifying the same with us in writing and obtaining our prior written consent. Please note that any non-compliance with this letter will leave us with no alternative but to initiate appropriate legal proceedings, both civil and criminal, against you and any other responsible parties.”

It's true. The donations Star Cement and others made to the BJP are legally permitted. When it comes to locating quid pro quo in corporate donations to political parties in power, India’s anti-corruption laws are quite muted.