New Delhi: Election Commission of India’s (ECI) top officer in West Bengal, the Chief Electoral Officer, sent instructions informally to state officials through WhatsApp, altering the rules by which the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the voter roll was being conducted in the state. Some of these instructions were in contravention of the written orders passed by the Commission, The Reporters’ Collective has independently confirmed.

All India Trinamool Congress (TMC), governing West Bengal, had first alleged this in a plea by its Parliamentary Party Leader, Derek O’Brien, before the Supreme Court. The Collective was able to verify the content of the WhatsApp messages independently through multiple state officials and a source in the ECI. The Supreme Court has issued notice to the ECI on O’Brien’s plea.

We also learnt that during virtual meetings, some state officers had asked the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) of West Bengal to provide specific orders setting and altering the voter revision process. We confirmed this from three officials in attendance.

Two of the messages that all officials pointed to and claimed to be in contravention of the laid-down rules of SIR was to advance the voters’ deadline for initial registration under SIR, called enumeration. The formal rules gave local election officers time till a formal deadline to include voters in the draft list. However, instructions issued solely on WhatsApp, advanced this date and asked officials to mark voters absent even before this deadline elapsed. The WhatsApp instructions also said that the election officers would complete the three home visits in this shortened time, also mandated in the written rules, before marking the voter absent before this new date. We verified the informal instructions. Two officials showed the messages, and a third independently confirmed receiving them as well.

Multiple officials stated that they were initially informed that the ECI would provide a ‘roll back’ option on the database. This was intended for cases where voters were prematurely removed from the draft roll but reappeared before the formal deadline; however, this roll back option never materialised.

Government regulations bar officers from operating on the basis of informal communications. Regulations strictly require all orders and communications between officials, including those in the ECI, to be put down on formal records and filing systems to ensure accountability and transparency.

The Reporters’ Collective has previously reported that ECI discarded its existing voter registration manual, claiming the SIR is an unprecedented ‘purification’. ECI then set new protocols and rules as they deemed best. While the initial orders instituting SIR were made public, dozens of operational orders and instructions that were subsequently sent to state officials were not made public by the ECI. Many of these orders impacted how voters would be required to re-register on the voter list, as well as dictating how the ECI’s ground teams would verify their rights to put them on the draft voter list or not.

This, to begin with, departed from the previous norm. Where ECI for past revisions has publicly detailed each and every process of voter registration to keep citizens informed. Now, the use of oral and informal orders on private messaging groups to state officials goes a step further. This report is the first such documented and reported instance of senior ECI officials operating out of a black box.

There are times when, due to urgency, instructions are given orally or through informal routes. Regulations require even these to be subsequently noted down on formal records. We asked the ECI and its West Bengal CEO if the WhatsApp orders had been subsequently put on formal records. They did not reply.

These messages were shared through a WhatsApp group comprising the CEO of West Bengal and the state’s District Magistrates, who were designated as District Electoral Officers (DEOs). These WhatsApp messages were sent during the enumeration phase of the SIR. The WhatsApp group has been in existence for a while. Multiple officials said that it was during the SIR that, for the first time, they received instructions on the group that went beyond the manuals and written orders.

The use of WhatsApp and other messaging systems in governments has become ubiquitous. But its use in contravention of laws and regulations by the Union government has been reported by the media only once in the past.

The ECI and the CEO of West Bengal did not reply to our detailed queries pertaining to the use of WhatsApp to pass instructions for the SIR in West Bengal and other states. Besides other clarifications, we had asked for copies of all such orders. The story will be updated if they respond.

The use of informal orders on WhatsApp overlapped with the ECI deploying undocumented software in the middle of the enumeration phase of SIR, which The Reporters’ Collective has investigated and reported earlier. These investigations can be read here and here.

The software malfunctioned, initially branding more than 3.66 crore voters as suspicious in just two states. Once flagged under the software as ‘logical discrepancies’, the voters would have to prove their identities, voting rights and citizenship with documents, even though the written regulations for the second phase of SIR did not require them to.

{{cta-block}}

Initial written orders in the public domain from the ECI headquarters or the CEO West Bengal for SIR did not mention the usage of the software. Less than two weeks before activating the software, the ECI had informed the Supreme Court that it was averse to the use of computerised programs to detect fraudulent voters as it had found its software defective.

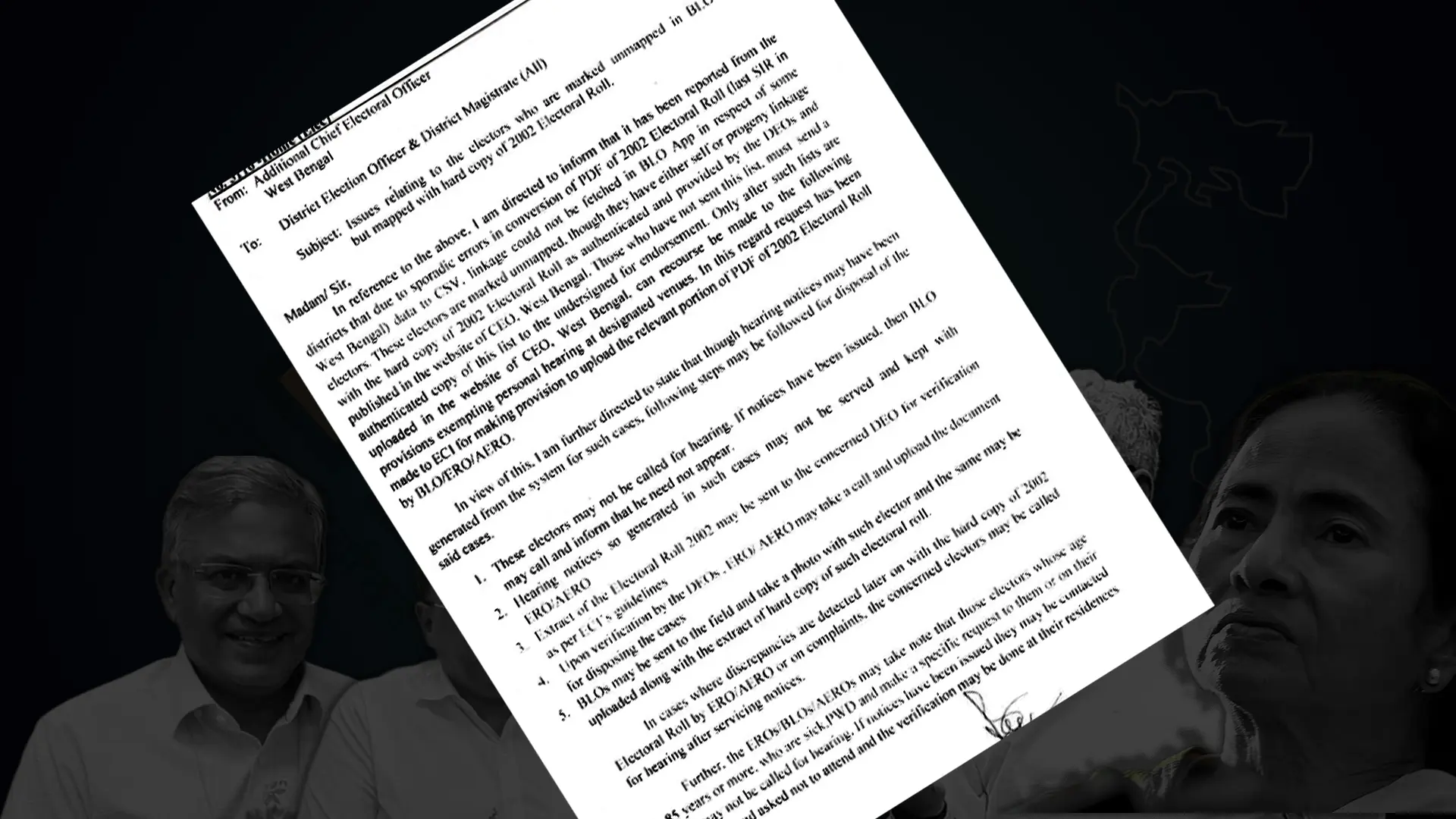

On December 29, after the enumeration phase was complete, the CEO West Bengal’s office admitted on record to state officials that the software finding ‘logical discrepancies’ was malfunctioning. This was because the base data, the 2002 voter list, had not been digitised accurately, the CEO admitted. Rules, this time in writing, were changed yet again to deal with the huge suspicious voter list thrown up by the software. District election officers were informed that some electors may not be called for a hearing, even if notices had been issued on the basis of this software.

The software was also tweaked to bring down the number of voters that were branded suspicious.

“Two sets of voters now have to prove their citizenship and voter rights instead of one. The ones who said they or their relatives were not on the 2002 voter list and those who said they were, but the software, with all its problems, still flagged as suspicious,” one state official said.

“Both sets of voters now have to prove their voting rights afresh with documents, though the SIR was carried out by ECI, claiming only those who were not ‘mapped’ to the 2002 list would be,” he added.

Another district election official told The Collective that by now it's not clear which orders are emanating from the West Bengal CEO’s office and which are from the ECI headquarters.

“In case any of these instructions wrongfully extinguish voters’ rights, who will be held accountable?” he asked, rhetorically.

A third official claimed that the level of scrutiny being imposed on voters in West Bengal is a notch higher than that in other states. He pointed to how the verification of suspicious voters is to be carried out. The state officials need to upload photographic evidence of the hearings being held in the presence of micro observers. The hearings for voters to present their papers have been restricted to 160 centers, mostly at the block level. “You can imagine how lakhs of voters will get a fair hearing at so few centralised centers, when the process has become increasingly onerous," he said.

We could not independently verify if the voters’ evidence verification process differs on these counts in 11 other states undergoing the SIR alongside West Bengal. The formal and detailed instructions to those states by the ECI and the state CEOs have also not been made public.

.avif)

.webp)