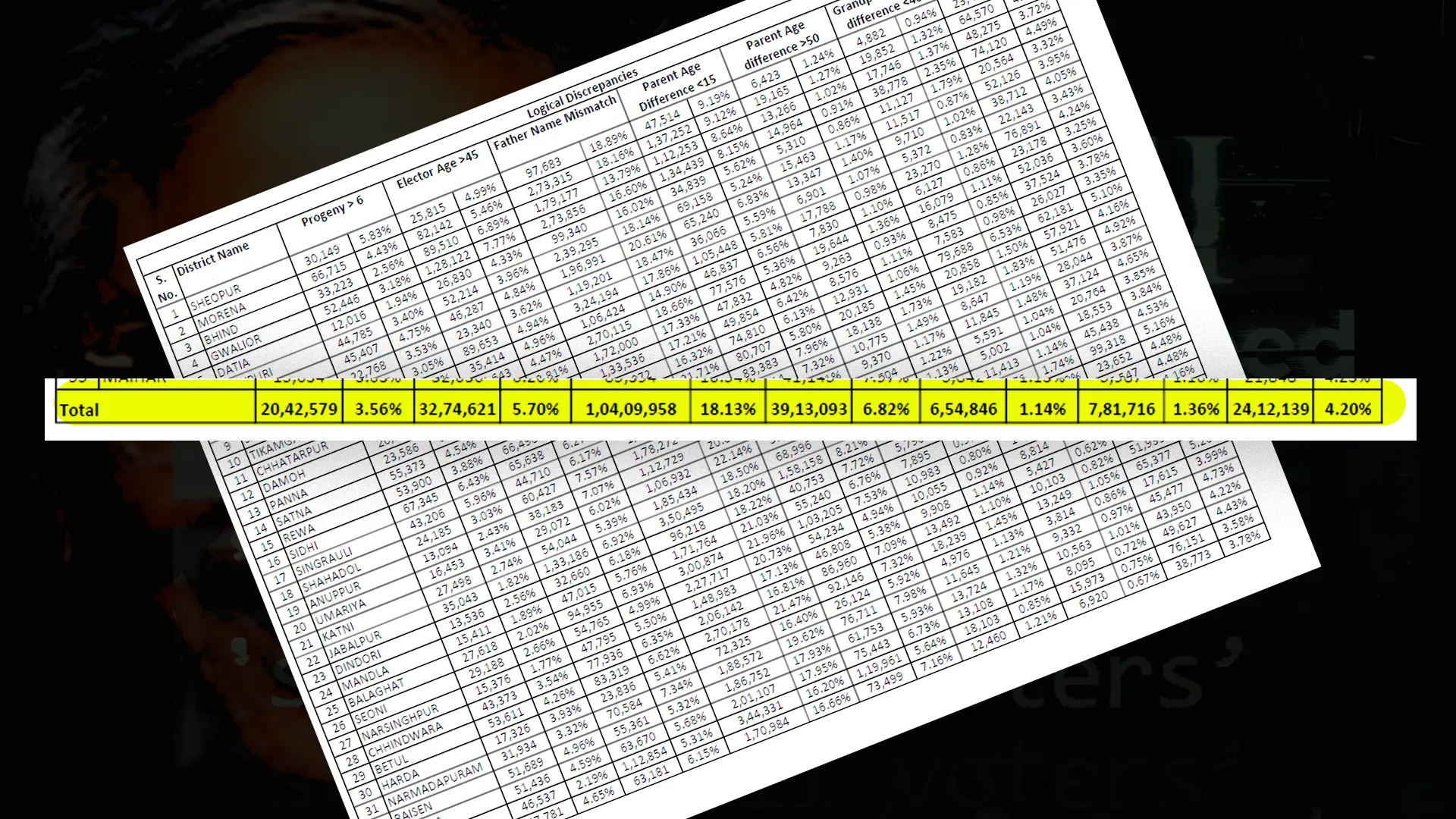

New Delhi: The untested software deployed by the Election Commission of India (ECI) without written instructions, protocols and manuals, red-flagged 1.31 crore voters in West Bengal and 2.35 crore voters in Madhya Pradesh as suspicious, putting their voting rights in jeopardy.

These voters earmarked as suspicious comprised a whopping 17.11% of the voting population in West Bengal and 41.22% of the voting population in Madhya Pradesh.

Crores of other voters were earmarked as suspicious across 10 other states that are undergoing voter reregistration as part of ECI’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR), independent sources confirmed.

The ECI euphemistically termed these as cases with “logical discrepancies”.

The Reporters’ Collective accessed the suspect list summary of two states, which were drawn up in the first half of December. Data from these records are being made public for the first time. The ECI has kept such details for all 12 states undergoing the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of voter rolls locked away from public scrutiny.

This software, used to identify voters as suspects, relied on the digitisation of physical voter lists from more than 20 years ago. The digitisation had been carried out across the 12 states in haste.

Detailed tests were not carried out in each state to verify the quality of this digitisation – whether computers could read these records and match them with voters’ inputs properly or not. This likely led to software misidentifying voters as suspicious, a senior ECI official in the state confirmed to The Reporters’ Collective.

ECI’s regulations require that whenever doubts are raised about a voter’s rights, these are resolved by a ground verification and a formal hearing by election officials at the constituency level. The ECI had not laid down in writing what evidence by voters would suffice to counter the computer-generated doubt about their rights. Taken aback at the unprecedented scale of suspicious voters flagged by its software, the exercise to check the crores initially marked suspicious was abandoned across states, even as the SIR rolled on.

At least in one state, The Reporters’ Collective can confirm that the Commission kept repeatedly tweaking the software while the exercise was ongoing. This got the number of suspicious cases down with the passage of time. Meanwhile, it was left to the last-mile Booth-Level Officials (BLOs) and constituency-level election officials to work with discretion rather than any established protocol.

In West Bengal’s case, 1.31 crore voters were marked as doubtful on a list generated in mid-December. By January 2, this number had dropped to 95 lakh, The Hindu reported, citing sources in the state chief electoral officer’s office. However, no reports were released to explain how the 34 lakh cases marked suspect by the ECI’s software had been resolved.

This is the first recorded time that the ECI ended up raising doubts about the rights of crores of existing voters based on opaque algorithms, without the safety layer of ground verification and established protocols for resolving the doubts by officials.

The ECI has not made public any records, protocols, data or orders about this failed attempt to use an undocumented and untested software to test the voting rights of crores of voters at risk.

In an earlier investigation, we had uncovered the ECI’s activation of two softwares in the middle of the second phase of SIR. This investigation shows the chaos and opaqueness that followed the use of one of these two softwares.

{{cta-block}}

The Mapping Business

Since announcing the SIR in June 2025, the ECI has made and bent the rules for the reregistration of voters on the go. It changed protocols once again during Phase 2 of the revision in 12 states.

After the Bihar SIR and into the next phase, the commission introduced ‘mapping’—a process that allowed voters to rejoin the rolls without showing their documents.

To do this, they had to prove that either they or their relatives were listed on a 20-year-old voter list. Those unable to prove this link were labelled ‘unmapped.’ The unmapped had to submit documentary evidence of their voting rights.

Weeks before states were scheduled to release their draft lists, the ECI introduced the mapping software, which flagged what ECI called ‘logical discrepancies’ in the mapping of voters against the two-decade-old lists.

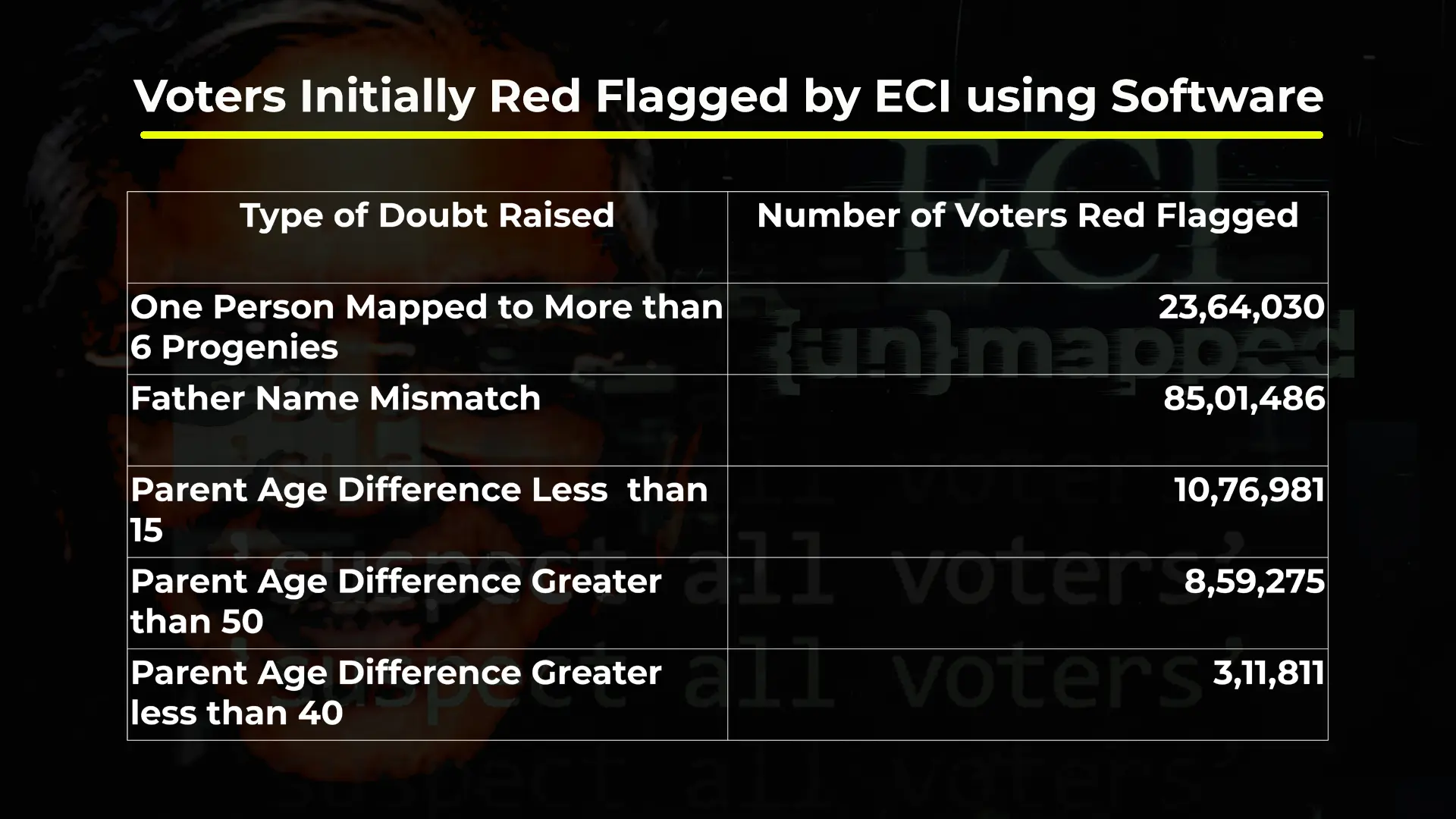

The software red-flagged all cases where:

- More than six voters had linked themselves to a single ancestor from the 2003 list;

- The age gap between a voter and their parent fell outside the 15-to-45-year range;

- A cited grandparent was less than 40 years older than the voter;

- There was a name mismatch between the relative cited and their entry on the 2003 roll; or

- The gender of the voter did not align with the name provided.

Until mid-December, the directive from ECI had been clear: only ‘unmapped’ voters would receive summons from Electoral Registration Officers to submit proof justifying their inclusion in the voter rolls. But as the year turned, ECI’s goalposts shifted.

In West Bengal, the ECI expanded its dragnet to include electors flagged for ‘logical discrepancies’ by its suddenly activated software.

Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar had bragged about this mapping back in October 2025, pitching it as a way to ease their bureaucratic burden.

Kumar had said, this ‘digital pre-mapping’ would handle almost all of the process, leaving only a small fraction of voters to undergo manual verification. He claimed, “the burden of proof was shifting from the citizens to the database.”

The idea was good on paper. It fell apart on the ground.

The mapping relied on two steps, where ECI’s new and undocumented process unravelled. First, the two-decade-old voter lists had to be digitised for voters to find themselves or their relatives on it. A senior officer at the state level in the ECI office told The Collective that the digitisation of the old voter roll was uneven and not tested for its quality.

“We don’t know if the digitisation was 95% accurate or 60% accurate in different states,” he said.

Independent researcher and privacy activist, Srinivas Kodali, explained, “The true accuracy of this digitisation exercise will only be understood when the ECI discloses its character recognition algorithms. Accuracy levels in digitisation can range anywhere from 60% to 90%.”

If the computer could not read the characters on the old list accurately, it potentially would generate wrong warnings. We asked ECI if it had tested its digitisation of the voter lists, and if it could share any report prepared for such an audit. It did not reply.

To top it, the BLOs too had been asked to type out data from the new enumeration forms into the digital database of ECI, which provided another opportunity for errors.

But the ECI’s voter registration juggernaut rolled on.

The Collective acquired a few of the ECI’s internal records, tracking the number of voters flagged, initially by this new software. In Madhya Pradesh, nearly 40% of the voters on the draft roll (2.35 crore voters) were deemed ‘suspect’ as their mapping contained logical discrepancies less than a fortnight before their draft list was published. In West Bengal, 17.11% (1.31 crore voters) of the voters were initially flagged for ‘logical’ discrepancies.

There is an irony in ECI’s sudden fondness for computer-generated lists of suspicious voters. The ECI had previously derided the use of such algorithms during the Bihar SIR, citing their high variability and the frequency of 'false flags' in the results. It told the Supreme Court, “The strength and accuracy of the results were variable and large numbers of suspected DSE (demographically similar) entries were not found to be duplicates.” Deduplication was therefore junked in Bihar.

But the ECI performed a policy U-turn immediately after, in the second phase of SIR, beginning with West Bengal. First, the mapping software was activated, and then the goalposts were shifted regarding the issuance of summons to voters to validate their rights.

The ECI had already armed itself and its foot soldiers in the district with wide powers for the SIR. In its directive to officials dated October 27, 2025, it had empowered the Electoral Registration Officers to conduct a suo motu enquiry in any case that they had any doubt about an existing voter ‘due to non-submission of requisite documents or otherwise.’

.webp)

This practically meant, an officer of ECI, at discretion, could raise doubt about any existing person holding a voter ID and turn them into a suspect. The ECI did not leave it to the officials. It began raising these doubts on its own, using the software it had activated.

Not all those red-flagged by the software are receiving summons from ECI. In the case of West Bengal, 24 lakh of the 95 lakh flagged will receive notices of summons, the Commission leaked to the press. No public disclosures on the criteria used to summon voters or resolve discrepancies have been made. We asked ECI about the criterion used, but they did not reply at the time of filing the report.

We previously reported how officials on the ground were now left to conduct the inquiry into crores of suspect cases of wrongful mapping. Except, they had not been told in writing how to conduct the inquiry, what evidence was adequate and what proof was needed to call a voter a voter. We sent official questions asking for this SOP to ECI and CEO offices of three Indian states, but none of whom replied so far.

The lack of written instructions continues to shroud the process, along with the opaque software algorithm and the bad scans of old voter rolls. In a meeting with officials from the ECI and the Chief Electoral Officer of West Bengal last week, district-level election officers explicitly requested written guidance on how to resolve "logical discrepancies." No such instructions had been provided by the time this report was published.

.avif)