New Delhi: After informing the Supreme Court that its de-duplication software was far too defective to be deployed, the Election Commission of India (ECI) has reactivated it midway through the revision of voter rolls in 12 states. However, it has done so after scrapping the rigorous ground verification process outlined in its manual for de-duplication. The quasi-judicial process was meant to reliably separate suspected fraudulent voters from genuine ones.

The ECI has also activated a second algorithm-based software midway into the revision of voter lists in 12 states, The Reporters’ Collective found. This too has been done without any written instructions, manual, standard operating procedures on record, or with information to citizens.

The Reporters’ Collective spoke to more than a dozen election officials in two states, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. We discreetly attended training sessions held by top officials for district-level ECI officers. We spoke to top district-level officials through detailed interviews. We videographed the workings of the de-duplication software, which has been switched on. We also witnessed the working of the second software that the ECI has turned on.

Many officials across the states preferred to speak off the record. In such cases, only claims that were triangulated and corroborated by at least three officials independent of each other have been reported.

We learnt that as the algorithms were introduced at the eleventh hour, no clear protocols or checklists were established for reverification, leaving booth-level officers and electoral registration officers scrambling to resolve flagged errors.

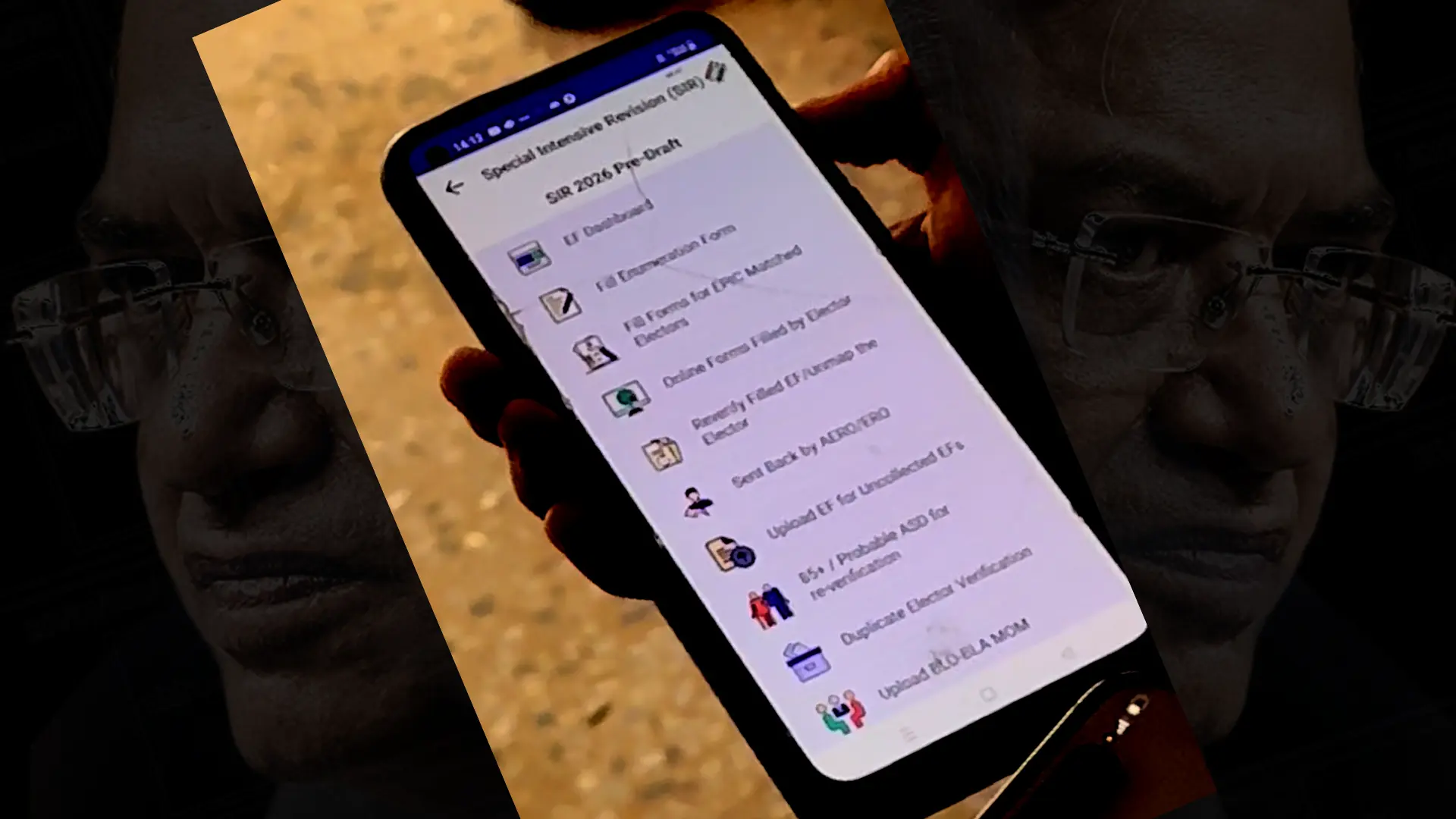

As one district election official put it, “Each day (of the SIR), our BLO app was populated with new tech protocols and lists. It showed ECI had no clear plan while running these algorithmic checks.”

The voter roll registration from scratch, called Special Intensive Revision (SIR), has already led to 86.46 lakh people being marked ‘unmapped’ and 3.7 crore people removed from the draft voter list in 11 states. The draft voter list for Uttar Pradesh is pending. It will be published on 31 December.

The use of uncodified algorithms without protocols in place to use has led to yet another layer of opaqueness and chaos, our investigation found.

We wrote to the ECI seeking copies of all written instructions and protocols for the use of these softwares. It did not reply.

{{cta-block}}

Switched Off

On October 7, The Reporters’ Collective revealed that ECI had failed to use its deduplication software during the Bihar voter roll revision.

This de-duplication software, in use since 2018, matches demographic details and photographs to throw up a list of voters potentially holding two or more voter IDs. The ECI manual required officials to carry out an elaborate exercise on the ground to verify if one or more people carried multiple voter cards, provide a quasi-judicial hearing to the voter and then delete any duplicate IDs.

But, in trying to register more than 7.8 crore voters of Bihar from scratch in mere three months, the ECI quietly did away with this critical anti-fraud measure. As a result, the finalised list of electors in the state was riddled with more than 14.35 lakh suspicious entries or duplicates, we found.

While announcing the SIR in 12 Indian states and Union Territories in October, the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) Gyanesh Kumar underlined, in a press conference, that no deduplication software will be deployed during SIR here as well.

Responding to irregularities pointed out in Bihar’s voter list, Gyanesh Kumar turned ECI’s manual for de-duplication, which he had not implemented, into an excuse. On August 17, explaining why duplicates remained on the rolls, he said, “There is a very extensive due process which must be carried out to remove duplicate voters from the list. We cannot simply strike a name off based on a claim; it requires field verification by the BLO and a legal window for the voter to respond.”

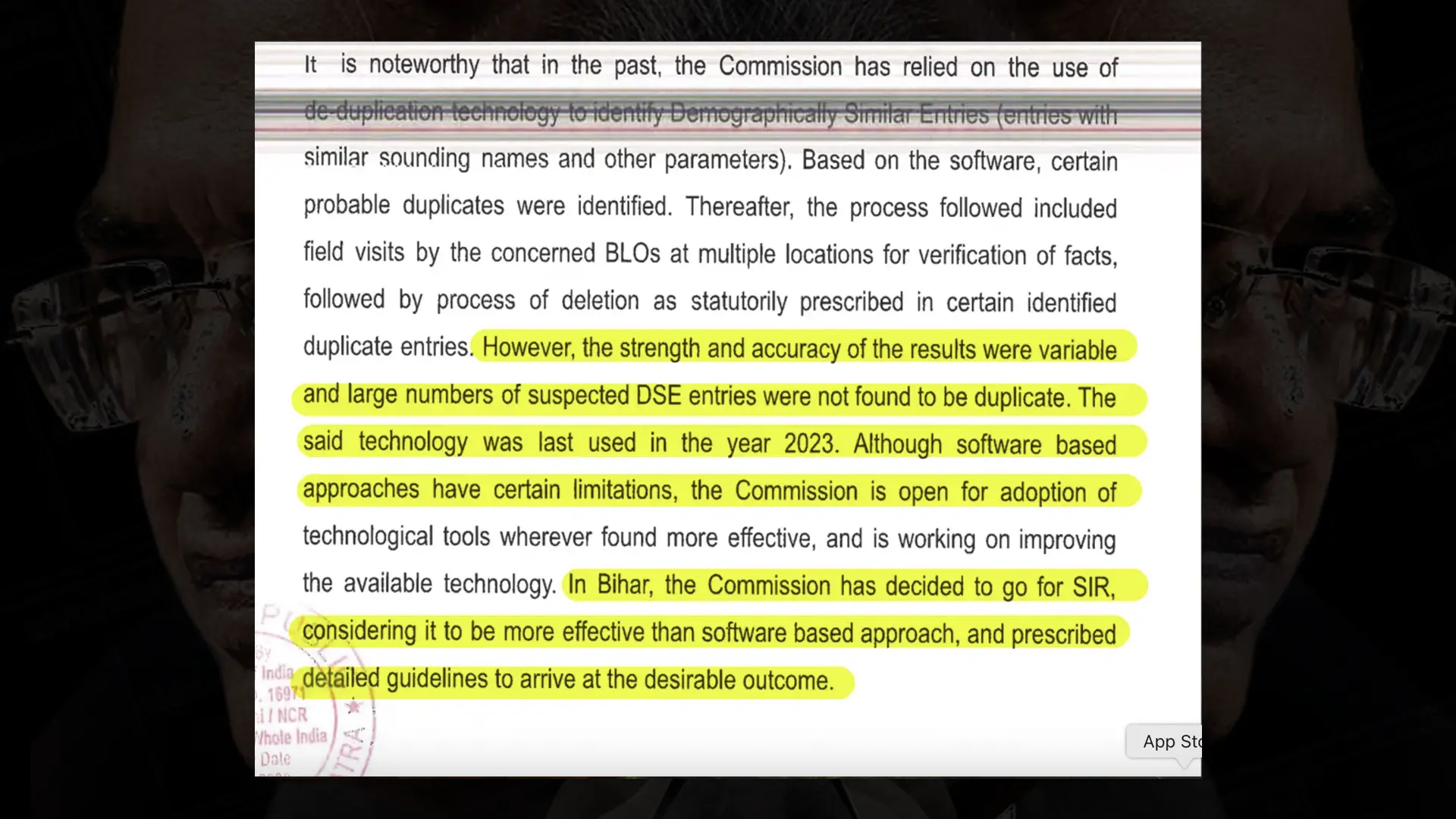

Findings of The Reporters’ Collective report were also cited in an ongoing case before the Supreme Court, forcing ECI to respond. On November 24, the commission disparaged its own software before the apex court.

It told the court, “The strength and accuracy of the results were variable and large numbers of suspected DSE (demographically similar) entries were not found to be duplicates. The said technology was last used in 2023.”

The Commission described its algorithmic system of detection as a software which made ‘random searches’. It said it had found a superior method for the SIR. It would depend on booth-level and other officials to manually detect duplicates across the country. It concluded that while “software based tools have certain limitations,” it was open to adopting technological tools wherever found to be more effective.

Switched Back On In 8 Days

The Reporters’ Collective has found that the ECI switched back on the software to identify suspect duplicate card holders merely 8 days after it told the Supreme Court the software was defective. It was switched on in the fourth week of the ongoing registration of voters in 12 states.

But, this time around, the ECI has junked its own manual and instructions, which require elaborate ground verification of the suspect duplicate cases.

No written protocols or standard operating procedure have been issued to district election officials or BLOs by ECI to resolve the suspect cases, we confirmed by speaking to eight district, constituency and state-level election officials across two states undergoing voter roll revision.

“We are applying common sense and logic to resolve these errors,” a District Election Officer (DEO) told us. He did not want to be named.

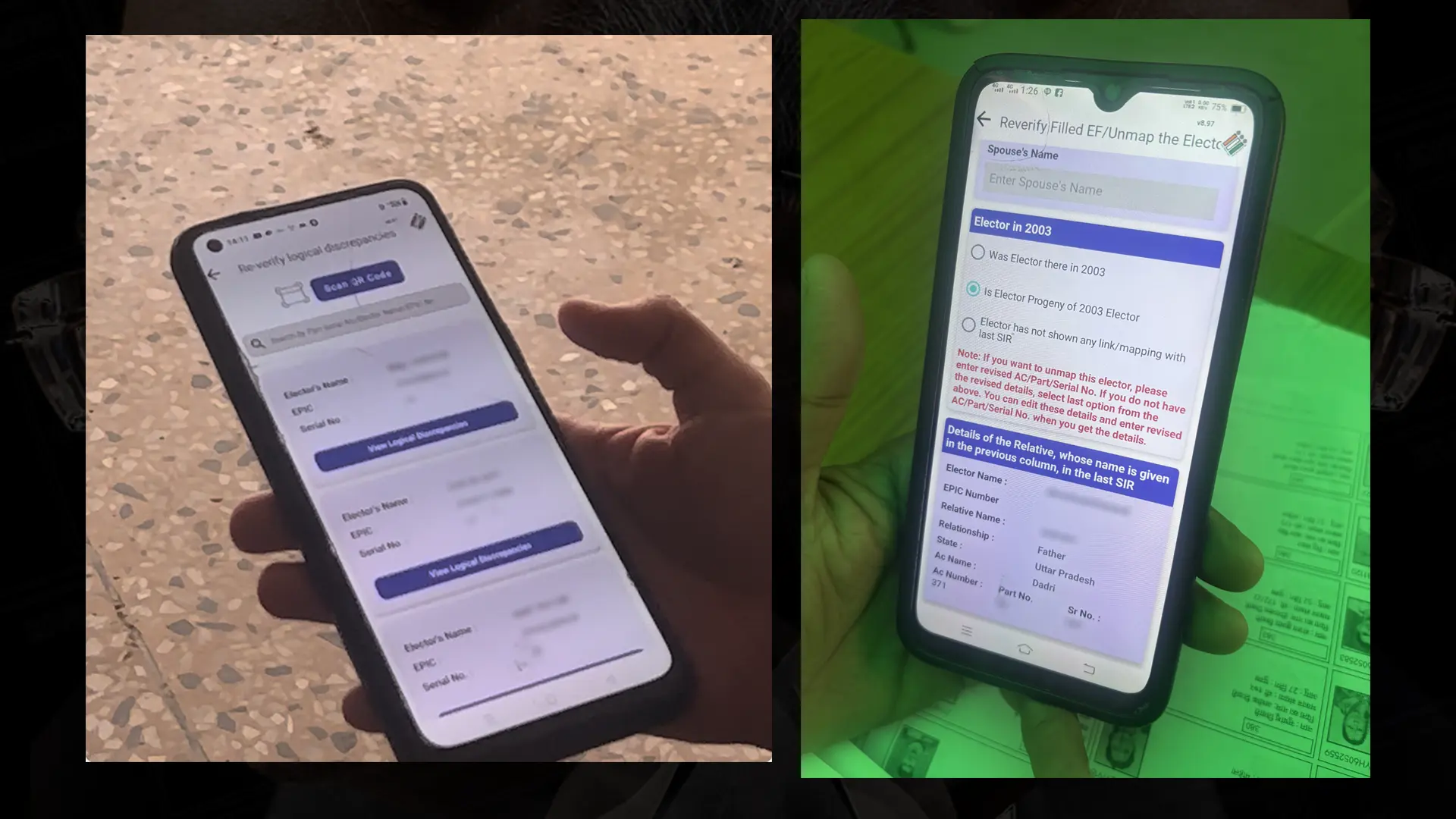

We saw the deduplication software working on the phones of booth-level officers (BLOs).

Lists of suspect duplicates (ECI calls them Demographically Similar Entries) began appearing on the BLO App, identifying voters with similar details either within the state or across the country.

On the app, the BLO is required to mark each entry as either ‘verified’ or ‘uncollectable’. According to multiple officials that we interviewed, operating without any written orders from the ECI, the BLO is allowed to use his own judgement to take such an action.

“A booth-level officer will have knowledge of voters in his own booth, and in case there are dual entries in his booth, he can automatically resolve that by removing one. In case one of the EPICs flagged is in the adjoining booth, he can coordinate with the booth-level officer there to see which EPIC must be included,” a district magistrate explained.

When asked if field verification and notifying voters of their duplicate entries were mandated in writing, the District Magistrate responded that BLOs would take these steps "as they see fit." These procedures were not specifically outlined in the written instructions; consequently, the legal window for voters to respond to their potential deletion was also not codified.

These are the rules for suo-motu deletions, according Rule 21-A of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960. A notice is shared on the address of the duplicate voter IDs, the elector is given a 15-day window to respond after which the ERO can proceed with their deletion.

While the ongoing field verification and visits by booth-level officers during the enumeration phase of the SIR mean that these rules are at least provisionally followed. Their abrupt and hasty execution on the ground shows that several steps are being short-circuited.

“The ECI continues to add new features to the BLO App as the SIR enumeration phase progresses. It shows that it is inventing processes and protocols on the fly with no clear plan,” a DEO based in Uttar Pradesh told us.

Quietly Deployed: Yet Another Software

In investigating how technology was being used by the ECI during the second phase of SIR without guardrails in place, we found the ECI deployed yet another software mid-way into the second phase of SIR without documenting its use for citizens or putting out detailed instructions for even its own officials.

This is to ‘map’ the voters, as the ECI calls it.

To understand what it does and how it is working (or not) on the ground, it’s necessary to understand how the ECI has twisted the SIR process itself over the past months.

Remember, for the SIR, the commission treats 2002-2004 voter lists as a baseline.

For Bihar, the commission ordained that all those not on the state’s two-decade-old list would have to submit their citizenship documents. Additionally, depending on the year they were born, they would have to submit one or both of their parents’ documents as well. If voters could trace either of their parents to the 2003 list, then they were not required to produce their parents’ IDs, just their own. This, as expected, was messy. It set different standards for different classes of citizens to prove their identities and voting rights.

ECI changed the rules for the revision of voter rolls in the next 12 states.

Voters who could trace themselves or their ‘relatives’ back to the two-decade-old list were exempted from producing any documents. Others would be termed ‘unmapped’, and these would be issued notices to produce one of the 12 documentary proofs of their voting rights.

Who could this relative be (besides parents), and how would one have to prove they are relatives? The ECI again failed to put down written instructions for either the citizens or their officials to answer this question.

The only definition of who could be a ‘relative’ came from the Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar speaking to the media on October 27, saying this definition included “father, uncle or anyone of that generation.”

His oral statements hold no legal value.

We found that on the ground, the working definition of ‘relative’ has been interpreted by the BLOS to imply either parents or grandparents. Those who cannot prove such relations are called ‘unmapped’ by ECI, which essentially means that they have no links to the voting lists of the previous SIR.

The second software, now in use, without a written codified procedure for citizens to know, is to verify this ‘mapping’ by what election officials call, ‘logical discrepancies’.

A Map Without A Direction

In an effort to decode the ECI’s algorithms, we observed the final stages of the enumeration process in Uttar Pradesh. Our investigation involved interviews with more than 20 BLOs and six senior officials, ranging from District Election Officers to Electoral Registration Officers.

We sat in on an online training session led by the CEO of Uttar Pradesh and gained access to the BLO App used for digital coordination. Through this app, we observed how algorithmic checks flagged 'suspect voters,' producing lists that were then handed to BLOs for door-to-door reverification.

Here is how the ECI has deployed the mapping software amidst a chaotic phase 2 of SIR.

Across 12 states, BLOs got the voter list from the vintage 2002-2004 roll for their booths. They were told, from their experience, to manually link the voter in each house to their ‘relatives’ on this 2002-2004 list.

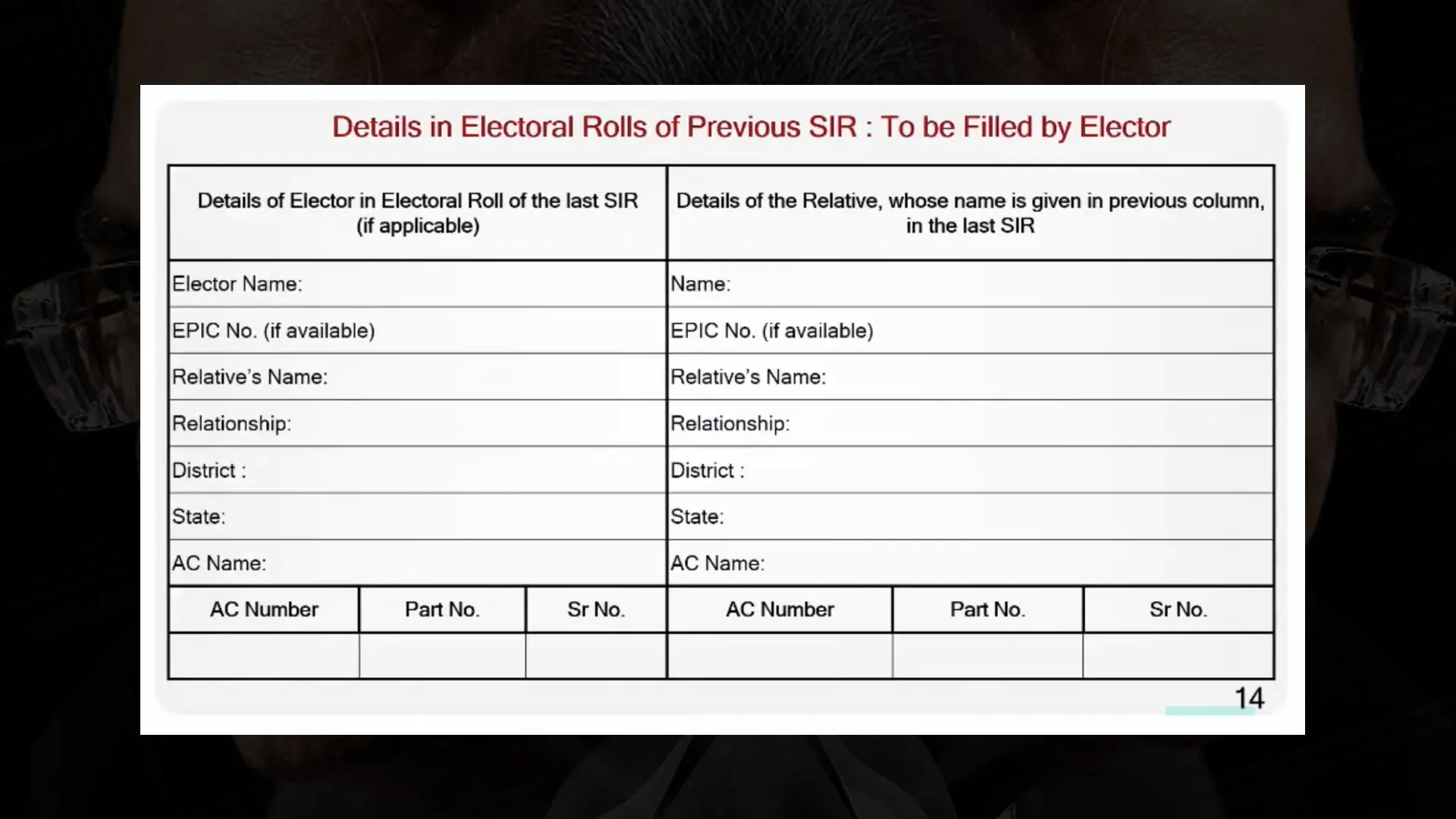

They took the physical enumeration forms along to each voter. The enumeration form this time included a section for the voter or the BLO to provide details of the ‘relation’, if one was found, for providing data linking to previous SIR voter lists. If neither the BLO believed a relation existed in the old list nor the voter insisted, the voter was declared ‘unmapped’, to be sent a notice to provide documentary evidence of his or her voting rights later.

Once the physical enumeration form gets filled, the BLOs are to take information from the physical forms and type it all into the ECI’s digital database through their BLO app.

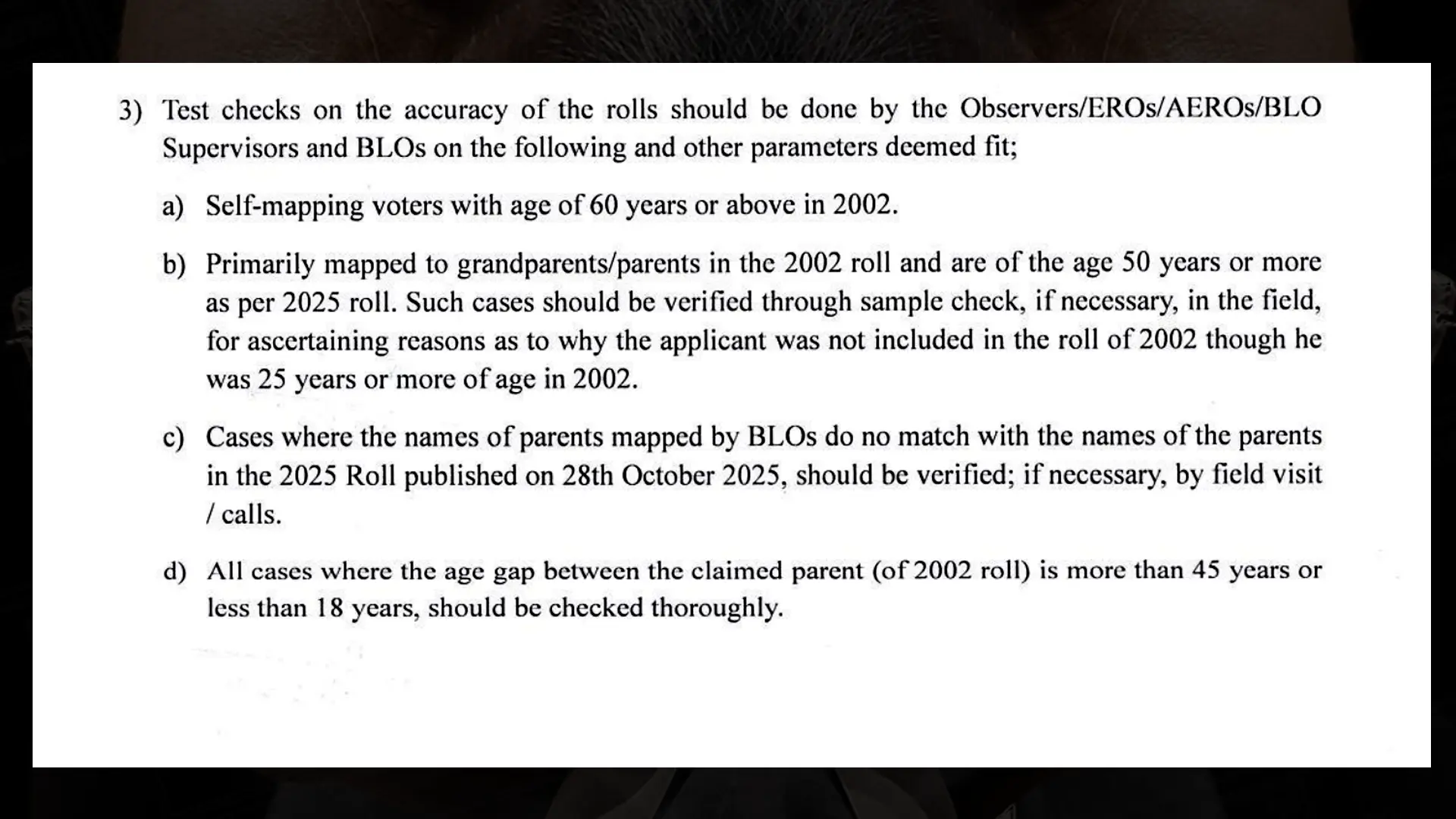

This is where ECI’s latest algorithmic check kicks in to track all possible errors. The first was a basic sum check of names as they are in the 2003 list versus those filled during the enumeration process. For instance, a voter could claim that his father, B.N. Rao was on the 2003 list, but if the name listed on the decades-old list was Bhanu Nath Rao, it would be flagged by ECI’s software.

ECI also introduced certain conditional checks. The difference in age between the voter and his claimed parent must be between 18-45 years. For grandparents, the age difference must be over 50 years.

There were a few additional categories of errors that the officials we interviewed claimed the software could flag; however, we were unable to validate these capabilities across all interviews. As far as we can ascertain, no written manual regarding the software’s functionality exists in the public domain, nor have the officials we interviewed pointed towards its existence.

What is clear, however, is that once the software flags a suspicious voter, which ECI internally calls a ‘logical discrepancy’, it mandates local election officials or the BLO to do an additional verification of these entries. Those who do not clear this verification will also be marked as unmapped when draft lists are produced.

All unmapped voters on the draft list will be issued notices during the ongoing verification phase. They must produce documentation for their inclusion within the 30-day period.

According to more than 20 BLOs and district and assembly level officials that we spoke to, ECI’s software to point suspicious voters for reverification was introduced in the eleventh hour, mere days before states were set to conclude their enumeration phase. We confirmed this in at least three states, Gujarat, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh. We extensively interviewed officials in Uttar Pradesh, in particular, to track this process more comprehensively.

In Uttar Pradesh, officials began receiving lists of voters with ‘logical discrepancies’ around 18–20 December, just days before the initial 26 December deadline for publishing the draft voter lists.

The lists appeared abruptly on the BLO App; ground officials and supervisors had received no prior notification regarding this additional step.

“I found out about this (logical discrepancies) yesterday (21st December). We’d completed the whole process, now we have to start over. We haven’t gotten any proper training but we were told in a meeting how this shall be dealt with,” a booth-level officer working in Ghaziabad told The Collective on conditions of anonymity.

On December 20, the Chief Election Officer of Uttar Pradesh held a statewide virtual meeting of district and assembly-level election officials. Our reporters were able to attend parts of the meeting. Election officials were seeking clear protocols and clarifying doubts on how to resolve these errors flagged by ECI.

According to the election officials interviewed, the first few days following the software's introduction were spent determining how to verify the new lists of 'suspect voters' provided by the ECI. As of Christmas Day, the prevailing instructions for BLOs include field verification, a signed undertaking by the BLO confirming the mapping, and the collection of one of the twelve ECI-mandated documents to prove citizenship. These are oral instructions given by the UP CEO’s office, with no clear written SOP circulated. ECI was also forced to extend the date for publishing the draft rolls to December 31 to allow BLOs to conduct the secondary verification.

The two software applications are now being used by the ECI without any written record in place for citizens or its own officials to follow. The SIR juggernaut rolls on.

.avif)