Jale, Bihar and Delhi: In 142 constituencies of Bihar, our data analysts detected a staggering 5.56 lakh suspect cases where the Election Commission of India (ECI) has registered the same person with two voter IDs. In each of these cases, the names of the voters and their relatives match completely, we found. They have been registered twice on the state’s draft voter list with an age difference on the IDs of 0-5 years.

In 1.29 lakh of these cases, the ages of voters on their duplicate IDs also matched.

The number was astonishing. We decided to go and meet some of these suspect duplicate voters. We reached the Jale constituency. Bihar’s urban development and housing minister, BJP’s Jibesh Mishra, is a two-time legislator (Member of Legislative Assembly) from Jale.

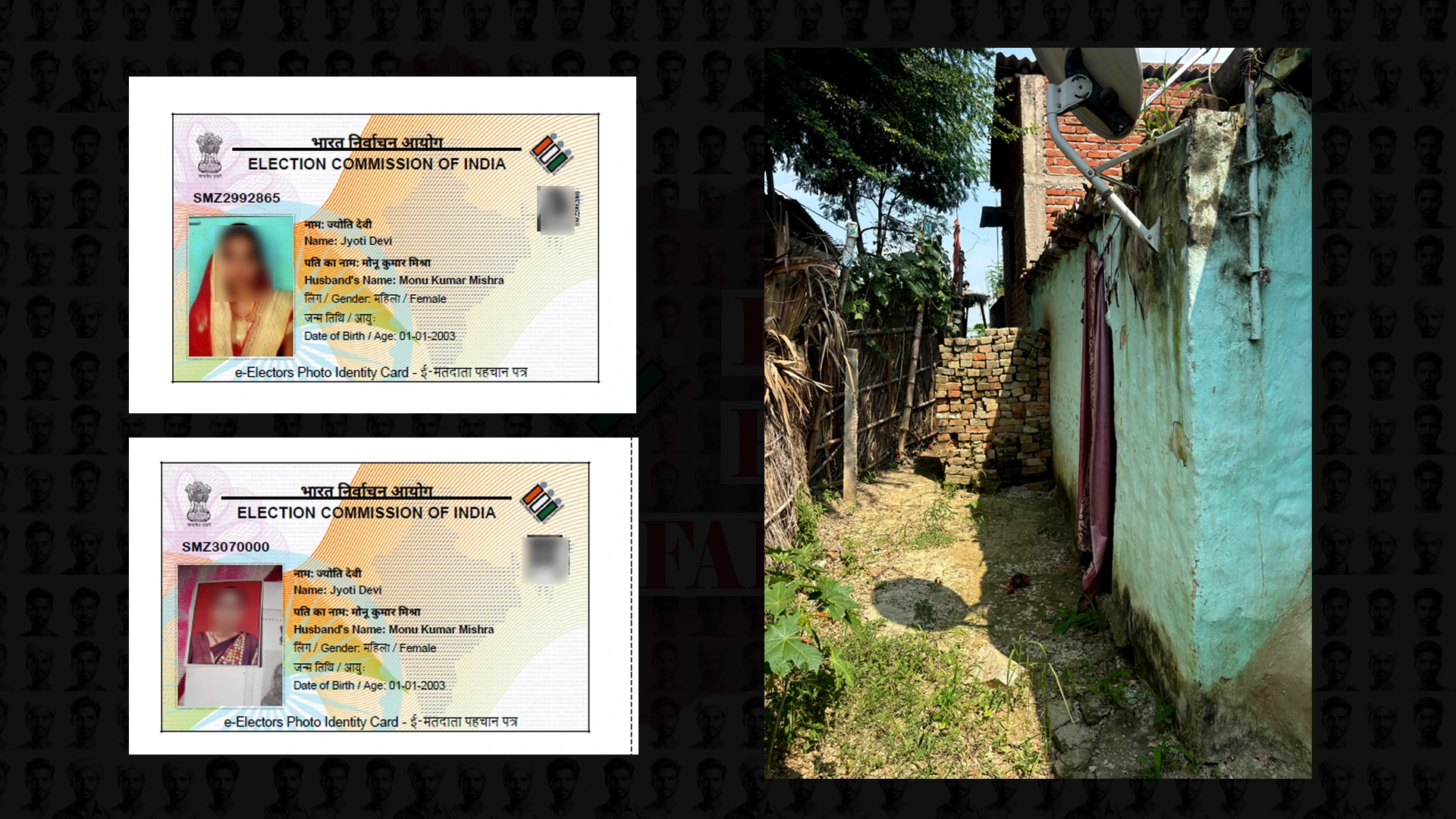

We were looking for 20-year-old Jyoti Devi. She has been registered to vote twice in Bihar’s upcoming assembly elections, our computer-matched data showed.

Jyoti Devi has not lived in Bihar for a while, we found.

The front path of her small, tin-roofed house was overrun with grasses and weeds. Like countless other families from rural Bihar, she and her husband, Monu Kumar Mishra, moved to Delhi six months ago in search of work, her neighbours told us.

She may not live in Bihar, but the ECI, in its self-proclaimed and hasty ‘purification’ drive of the state’s voter roll, has registered Jyoti Devi twice against different IDs with all the same details except for her address and two different passport photographs.

Cases like hers could have been the easiest to detect during the mandatory computerised de-duplication process that the ECI and its officials are required to undertake before publishing the draft list. The ECI has a sophisticated software program that matches details, including photographs of voters, to remove duplicates after a physical verification. Jyoti Devi and more than 5.5 lakh similar cases like hers have escaped detection in Bihar and could now potentially vote twice.

Their relative, Pappu Mishra, provided identity papers for Jyoti when booth-level officers came to re-verify details for inclusion in Bihar’s fresh voter lists during July’s Special Intensive Revision. Pappu does not recall submitting Jyoti’s details on two separate enumeration forms during the 30-day revision exercise.

We checked both of Jyoti’s Voter IDs (called EPIC) on the Commission’s online database. For both EPICs, mysteriously, her identity papers have been uploaded. We spoke to ECI’s booth-level officers who were unable to explain how Jyoti Devi appears twice on the voter rolls.

Hundreds of Photo Match

Jyoti Devi is not an exception. Neither is Jale. Bihar’s new draft voter list is littered with suspect duplicates. We earlier took help of a group of data analysts to match records across different constituencies using computerised detection. They had cracked the ECI’s padlock on the voter data to do it. This time, we went a step ahead.

The Reporters’ Collective collaborated with Citizenry, a tech-driven political consultancy, which has been in the business of analysis, campaign strategy and electoral advisory for several years. In the Madhuban constituency, they accessed hundreds of voter IDs with the photos of the voters. They matched not just the recorded data but the photos as well. And then verified several on the ground.

“We developed an algorithm that cross-checks each voter against the database, identifying potential matches based on names, guardians, and demographic patterns. Our system flagged over 6,400 potential duplicate registrations in Madhuban, out of which our eight-person verification team conducted systematic photographic verification of around 600 cases from every booth across the constituency, providing concrete proof of identical individuals holding multiple EPIC numbers,” said Ahtesham Ul Haque, the Founder of Citizenry.

With their help, The Reporters’ Collective was able to unearth hundreds of cases where voters have been registered twice, sometimes with the same photos, at other times with different photos of the same person. And in some cases, we found that photos of men had been put on duplicate Voter IDs of women. The ECI had missed detecting all of these - an easy catch, if they had done the removal of duplicates thoroughly.

In Madhuban, the most striking evidence of duplication came not from spreadsheets and data downloaded on a computer, but from the draft voter rolls that the booth-level officers possess.

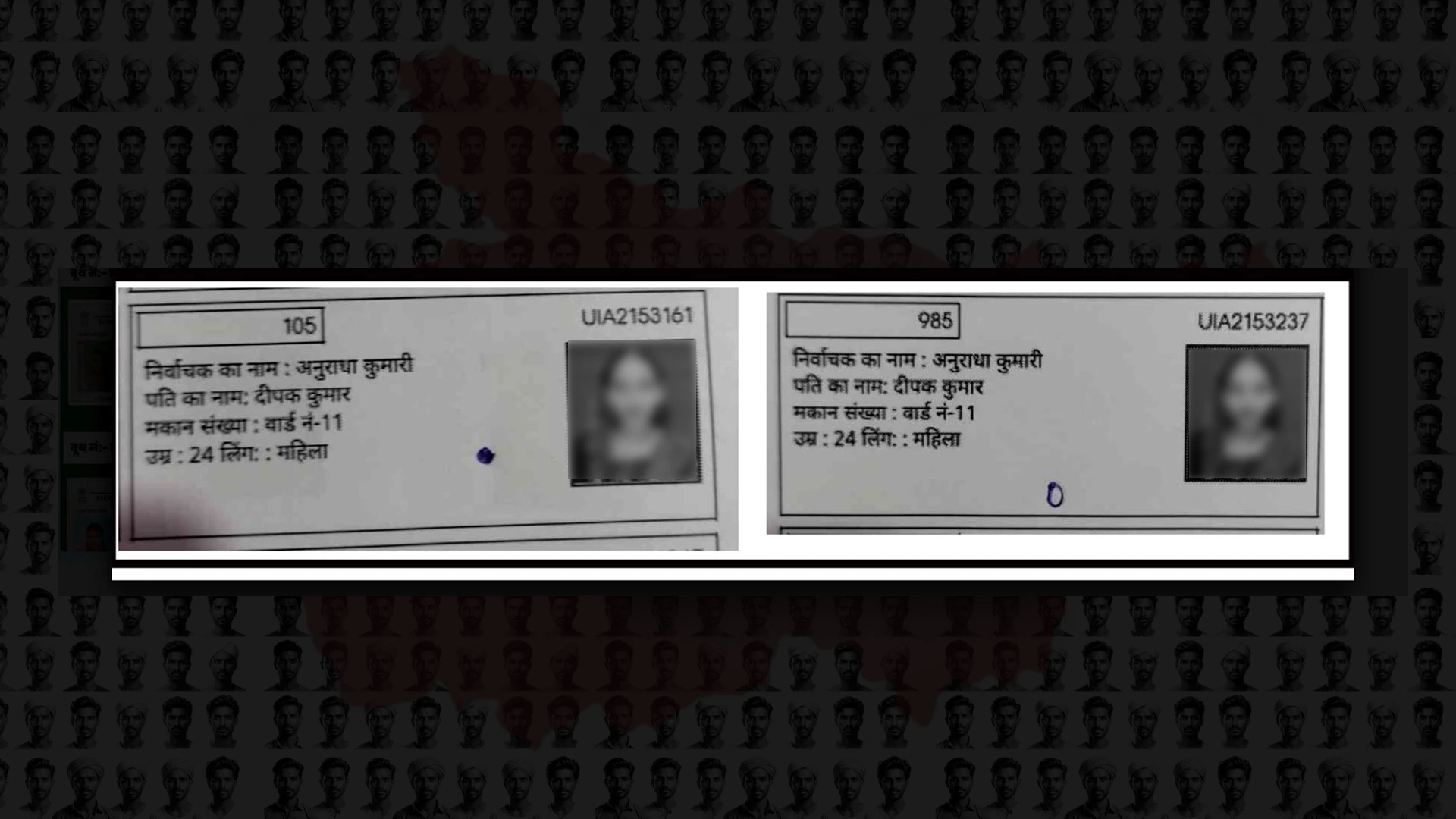

Take the example of Anuradha Kumari. She has been registered to vote twice. In both her Voter IDs, her name is spelt the same each time, and so is her husband’s. Even her age and house address are the same. To the eye, there is no ambiguity: the face is identical, the person is the same. Yet the roll treats them as two distinct electors.

In the curious case of Chuchun Sahni (UIA0302737), all the details, including his registered address and age, are the same as Chunmun Sahni’s (UIA0294116). The photographs differ slightly, but the demographic details are identical.

Barring the possibility that these are twin brothers, Chuchun and Chunmun, these are duplicate voter IDs.

But there are cases we unearthed, such as that of Nirmala Devi. In both her Voter IDs, her husband is Jeetendra Ram. In one Voter ID card, it is a woman’s photograph. For her other ID, the ECI has allowed a male’s photo.

Nirmala Devi’s recorded age difference on two IDs is just a year. Her house number changes from 12 to 129.

.webp)

The discrepancies are rampant and hard to miss at a simple glance. The face of the same person clicked over different times. A man, with and without a beard. A photo of a photo in one case, the exact same photo in others. In a handful of cases that we reviewed, we found men holding three or more EPIC numbers in the same constituency. The pattern repeats across dozens of pages of voter rolls. Each such voter entry has survived the ECI’s supposed thorough physical check and its claimed computerised detection systems.

The Big Picture

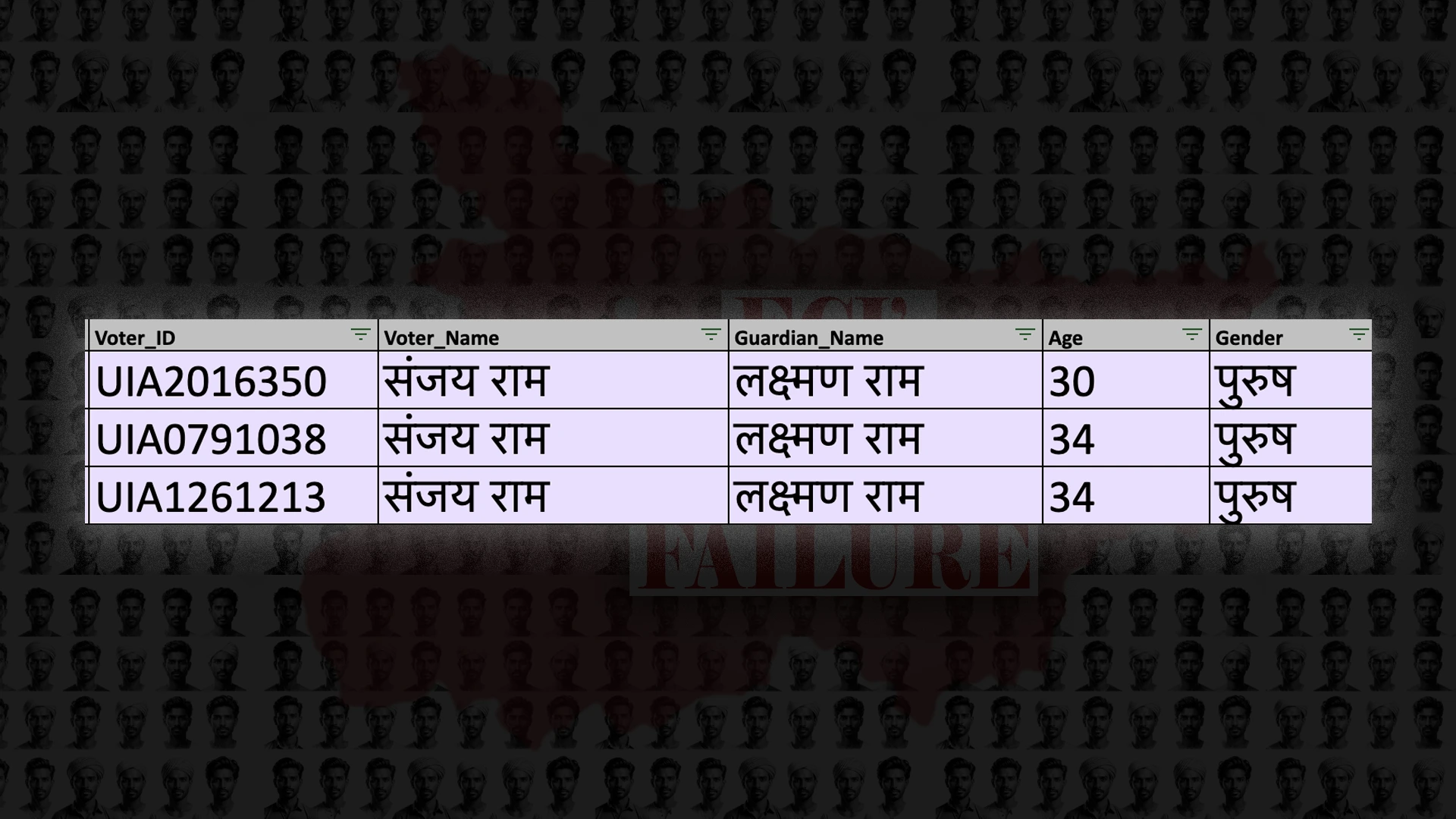

In our earlier investigation, we examined 39 constituencies of Bihar and found tens of thousands of duplicate voters: cases where one individual held two voter IDs within the same constituency. For this report, our data analysts expanded the scope significantly to 142 constituencies.

Using the same methodology, matching names, relatives’ names, and ages across entries, we identified an even larger set of duplicates that have slipped through the ECI’s claimed clean-up.

In just over 5.5 lakh cases, voters have been registered twice under the same names and relatives’ names, with only a minor age difference of up to five years on the two IDs.

In another 1.29 lakh cases, everything matches: names, relatives’ names, and ages. The only difference being the address on the voter IDs.

Of these, 40,649 cases are the most alarming: two voter IDs in each case with identical names, identical relatives’ names, same recorded ages, registered in the same or nearby polling booths. These suspect duplicates should have been the easiest for the ECI to verify.

The ECI’s software would have easily picked up another 2.40 lakh cases that we detected where the age gap between the two entries is between 6-10 years.

In an overall 10.22 lakh cases across the 142 constituencies in Bihar the names of voters and the names of their parents or spouses matched perfectly. The only differences were in recorded age, address.

Madhepura constituency tops the list with 9,411 suspect duplicates, followed by Singheshwar with 8,416, Paroo with 7,355, and Bihariganj with 7,103.

Election Commission’s Failure

The Election Commission had earlier tried to dismiss such detection of suspect duplicates, claiming many people in Bihar share common names, and so do their relatives. Even as it dismissed our previous reportage, it took the specific examples we had provided and removed the duplicates.

It is true that in some cases, the ground check could reveal some similar looking Voter IDs belonging to two distinct people. We found some during our ground verification.

In the Jale constituency, our team found a few such cases. Data analysis had thrown up Santosh Paswan’s name as a suspect duplicate card holder, with both IDs displaying the same name for the father. We found 47-year-old Santosh living in Kamtaul, Ahiyari, and another 46-year-old Santosh had a house in Bandhauli Panchayat in Baghaul. Both in the Jale assembly constituency.

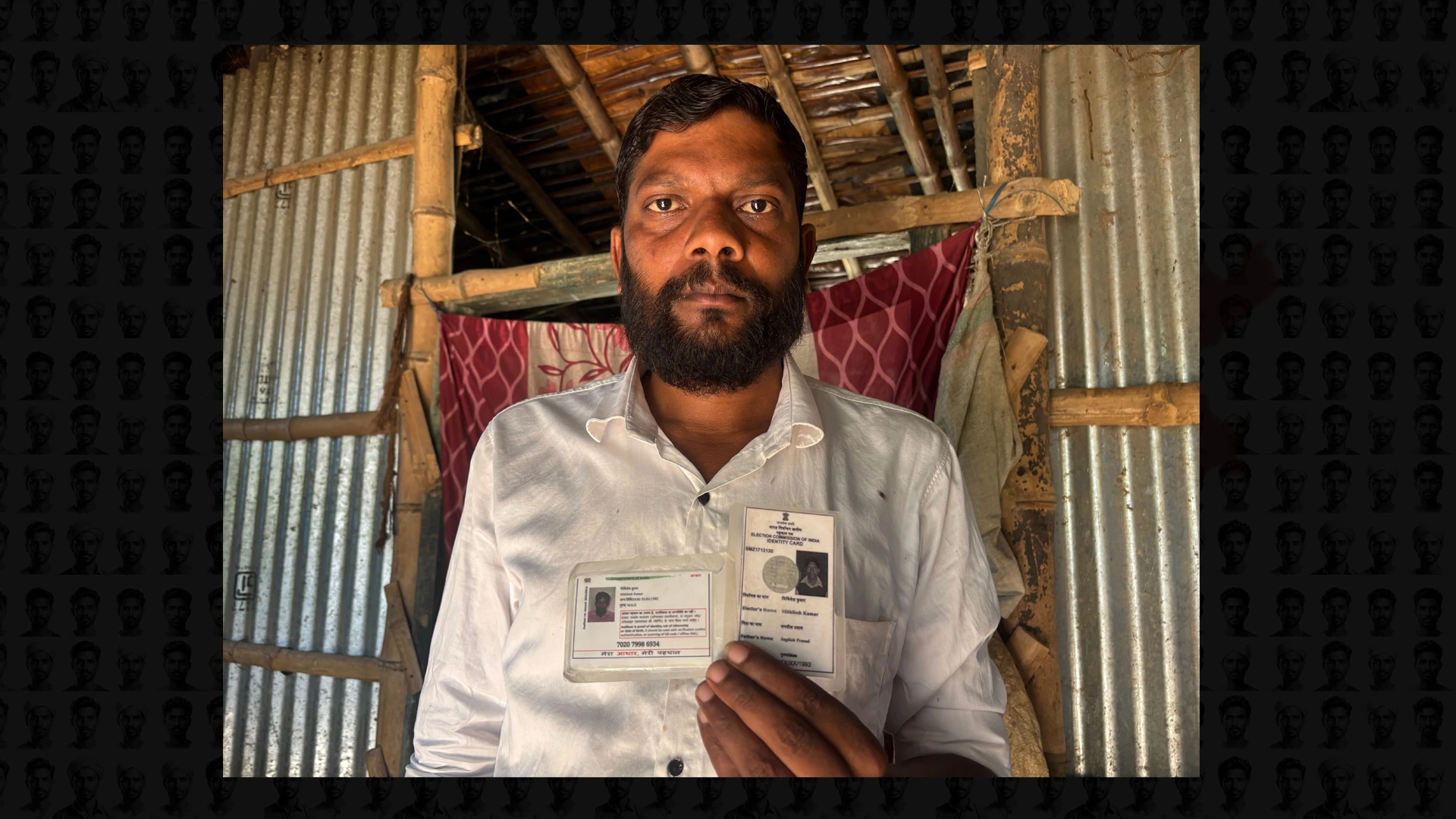

For every Santosh Paswan, there are several more Mithilesh Kumars. In Jale, Mithilesh Kumar has been given two Voter IDs. The thirty-two-year-old ran away from his father's home and moved to his maternal grandfather's house to till the land there. Mithilesh was registered on both of these addresses as a voter, with all identity papers duly submitted during the SIR exercise.

We met Mithilesh at his grandfather’s house near polling booth 300, in Panishala/Mankauli. He accepted that he had submitted his documents when booth-level officers came during the revision exercise, but he insisted that he had his name removed from the polling booth near his father’s house. “My name has already been removed from the ration card on that address. So how can I be registered to vote there?” he said.

Duplicate voters such as Mithilesh have existed for decades on India’s voter rolls. An official who worked at the Bihar office of ECI told us, “In my experience, voter rolls have always had floating dead voters and duplicates. You will find that if the elected representative is powerful or from the ruling dispensation, he holds the ability to get these votes put in his favour. There is a running underground economy of these votes during elections.”

Several people in states like Bihar end up holding two voter IDs as they migrate. Women often do so when they have to move homes after marriage. They often do not get the previous Voter ID deleted. These become available for fraudulent voters to unscrupulous political candidates. At times, for a price, the official said. Then, there are duplicates created specifically for bogus voting, he said. “Such cases are always likely to be higher where the ruling party’s MLAs are elected because you need the support of the local administration to do this fraud,” he added.

This time around, the ECI ordered a complete revision of the voter roll from scratch across India, starting with Bihar, claiming the databases would be cleansed of all faults. But the rules and methods it set for this revision, called SIR, were unprecedented.

Different classes of citizens in Bihar were asked to provide a differentiated set of documents as proof of their citizenship, their identity and their usual place of stay. Initially, the nearly eight crore citizens of Bihar were told they would have to submit the proof in 30 days while the booth-level officers spread out to collect their enumeration forms. Less than a fortnight into the process, the rules were changed. The officials were told to collect the enumeration forms without the documentary evidence. These could be submitted later, ECI said.

Booth-level officials admitted they had too little time to do any real verification.

In haste, the BLOs filled forms in many cases, after taking whatever documents they could get hold of from voters. Chaos ensued, as our previous reportage and that by many other journalists has shown.

The Election Commission maintains that “photographically similar entries” and “demographically similar entries” are flagged by its software and weeded out before the draft roll is published. The ECI claimed it had run the de-duplication process and weeded out seven lakh such cases before finalising the draft voter list. But the de-duplication process, going by its own instructions, requires giving people an opportunity to be heard before the second vote is deleted. This did not happen.

In 2022, the Commission claimed to have removed nearly one crore duplicates nationwide through this method. Yet, the existence of hundreds of photo duplicates in Madhuban’s electoral rolls and lakhs of suspect duplicates in 142 constituencies shows that ECI failed this time around, when it promised to be better than ever before.

Now, the ECI has claimed it will check suspect duplicates on the draft lists only if someone formally complains, though its rules permit the district Electoral Registration Officers to take action on their own if they suspect problems in the voter data.

Shunting part of its responsibility onto political parties, the ECI suggested that the latter should carry out the verification of the draft voter list more diligently and deploy more booth-level agents to do so. Before the Supreme Court, it has tried to prove that the political parties had not reported too many problems with the draft voter list.

But, it is the political party in power, in this case BJP and JD (United), which is quite naturally expected to have the resources to deploy more agents than the parties in opposition.

When the Supreme Court next hears the case against ECI’s voter roll revision soon again, the suspect 5.56 lakh duplicate voters of 142 constituencies remain unchecked.

You can read all our investigations so far into the Special Intensive Revision here under the Electoral Roll Project.

.avif)