Morena & Bhopal: Just as the western wind begins to blow towards Lohgarh Panchayat in Madhya Pradesh's Morena district, a miasma of foul smell emerges. The bad odour slowly spreads everywhere, depriving the villagers of their sleep after the day’s hard work, and those who hit their hay in the courtyards of their houses are covered with black dust. The situation is similar for the residents of Lohargarh and 13 other nearby villages.

A noxious cocktail of carcinogenic gases, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs), dioxins, furans, and oxides of nitrogen travels with the western wind from the Jaderua Industrial Area, located nine kilometres south of Morena city, abutting the Agra-Mumbai national highway.

Thirteen tyre pyrolysis oil (TPO) recycling plants sit inside the industrial area. Set up a decade ago, they incinerate scrapped rubber to extract pyrolysis oil, steel and carbon black.

The carbon black soot does not accept boundaries separating industrial areas from homes. Roofs and verandas of homes get coated in black soot. Trees and crops wear a dark shroud. It’s not just the air. Toxic water runs out into fields. Rivers have turned into toxic drains. These plants are only allowed to combust Indian tyres.

On paper, India banned the import of scrap tyres for extracting the pyrolysis oil in 2022. But it did not put a mechanism in place to monitor the ban. In fact, the import of waste tyres has consistently increased over the years, and pyrolysis plants in cities like Morena work overtime, burning imported waste tyres.

“The residents have been breathing cancer for the last decade,” says Yogendra Mawai, a professor of Pharmacy at Shri Ram College of Pharmacy, Morena, who has been researching the health impacts of the emissions on the environment and people for years. “These factories cook domestic and imported tyres many times higher than their permissible limits.”

“The carcinogenic gases increase risks of cancer in the lung, skin, and bladder,” says Sagar Dhara, Energy and Environmental expert from Delhi. “Release of heavy metals (zinc, lead, cadmium) from tyre residues can also accumulate in the body, potentially causing neurotoxicity, kidney damage, and developmental issues in children. These factories kill two kinds of people. First, those who are working inside the factory and those who live in its vicinity.”

Madhya Pradesh has 69 such pyrolysis plants, and, of those, Morena houses 20 plants. Thirteen of them are in Lohgarh alone.

At the cost of the health of the poor across the country, an illegal trade in imported rubber tyres flourishes, The Reporters’ Collective found. India, the fourth-largest economy in the world, with aspirations to become a ‘developed country’, has become the world’s waste tyre dumping ground.

{{cta-block}}

How India is Importing Cancer

In July 2022, India banned the import of waste tyres for pyrolysis plants.

It did not put the cogs in place to track the illegal flow of imported waste tyres. Loopholes existed to let the trade continue unabated. In fact, it grew multifold.

Waste rubber tyres are imported under a broader tag of rubber scrap. The tag, in international trade jargon, is an HS Code (Harmonised System Code). Customs officials worldwide identify goods by their HS code to know what is being shipped around.

There is no specific HS Code for scrapped tyres. They are traded under the broader tag of scrap rubber. A plain scrutiny of the HS code on shipping documents evades detection. Custom officials have to inspect and detect. If they want to.

If they want to, there is another loophole to breach the ban. Importing waste tyres was banned only for processing in Advanced Batch Automated Process (ABAP) plants, also called TPO plants (like plants in Lohgarh), which convert whole tyres into tyre pyrolysis oil, carbon black, and steel wire.

There are four other ways to process imported waste tyres. Those were not banned.

There was no mechanism put in place to detect if the waste tyres, once imported, were going to the banned TPO plants or elsewhere from the ports.

A paper trail could be faked to suggest they were going for other processes, but eventually could end up at the TPO plants, such as those in Morena.

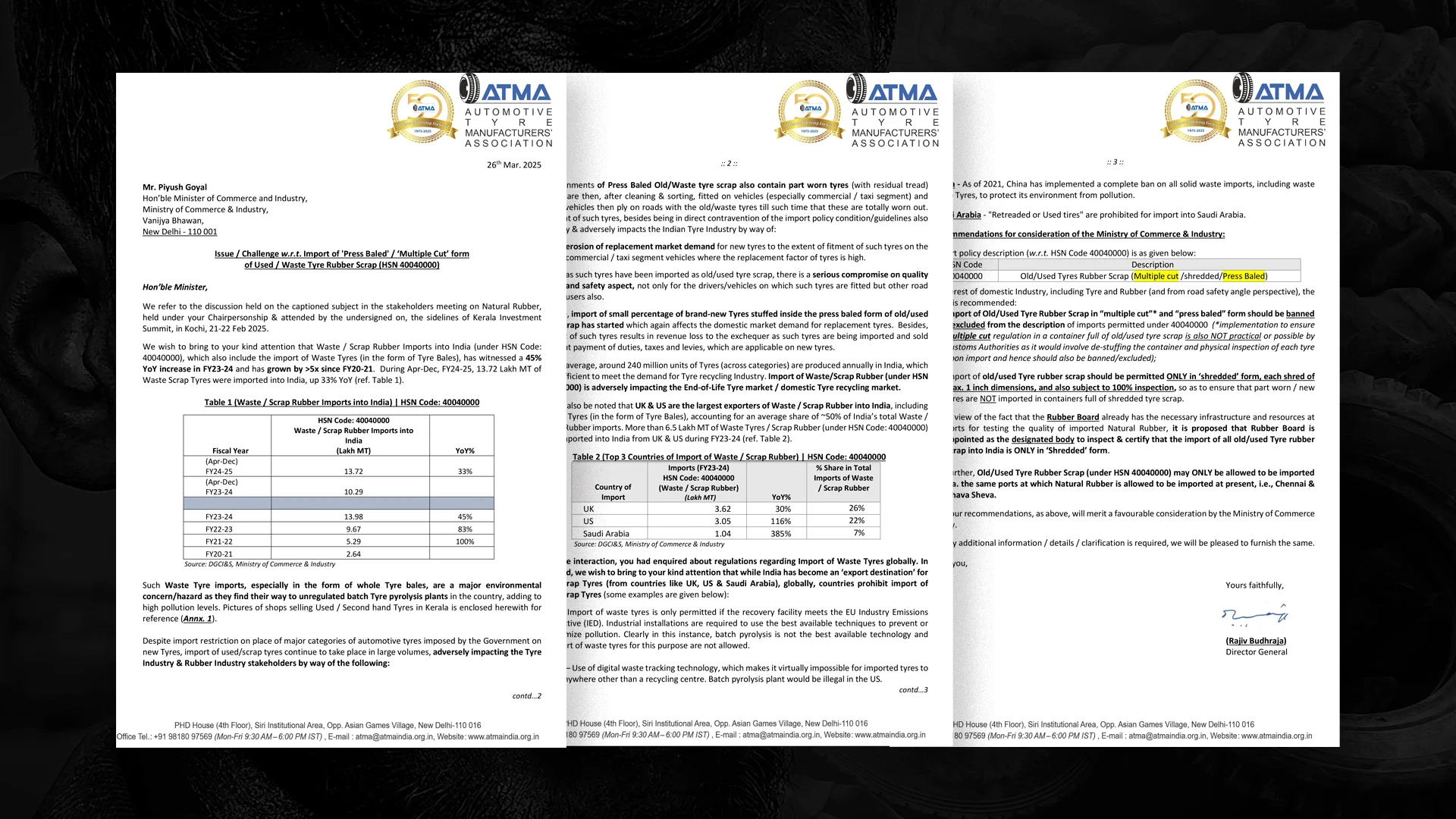

Between FY2020-21 and FY2024-25, the import of waste rubber increased fivefold, from 2.64 lakh metric tonne (LMT) to 13.72 LMT.

“The imports to India surged following India’s move to legitimise the waste tyre recycling industry through the introduction of the EPR policy in 2022,” said Satish Goyal, President of the Tyre & Rubber Recyclers Association of India (TRRAI), speaking to The Reporters’ Collective. “Demand for waste tyres rose sharply, while financial inflows from producers enabled upgrades in industry capacity and technology.”

Goyal implied, the policy to encourage recycling ended up bringing more waste tyres into India for burning.

Developed countries, such as the United Kingdom, Australia, the United States of America, and Gulf countries such as Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and others, which were struggling with the waste tyre problem, became some of the biggest exporters of waste scrap rubber to India.

Two reports of a UK-based NGO that collaborated with the BBC to track down the flow of waste tyres in India from the UK, in 2023 and 2024, showed that the scrap tyres ended up in TPO plants like Lohgarh and Wada, Mumbai, which houses dozens of TPO plants illegally.

Import of waste tyres can only be done for recycling under Indian law after obtaining a license from the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and the Ministry of Trade and Commerce to traders. Yet, we have confirmed on several occasions that foreign tyres are being burnt on Indian soil, not just recycled.

“We are paying to import pollution,” says activist Shubhash C Pandey, who tracks environmental violations in Madhya Pradesh. “We’ve paid crores to over 50 countries to bring their trash to our doorstep. Meanwhile, our people choke, our lands die, and our water turns black.”

The Reporters’ Collective traced the trade. Through documents and sources. We redrew the trail from the ports to the pyrolysis plants.

The Journey From Port to Plants

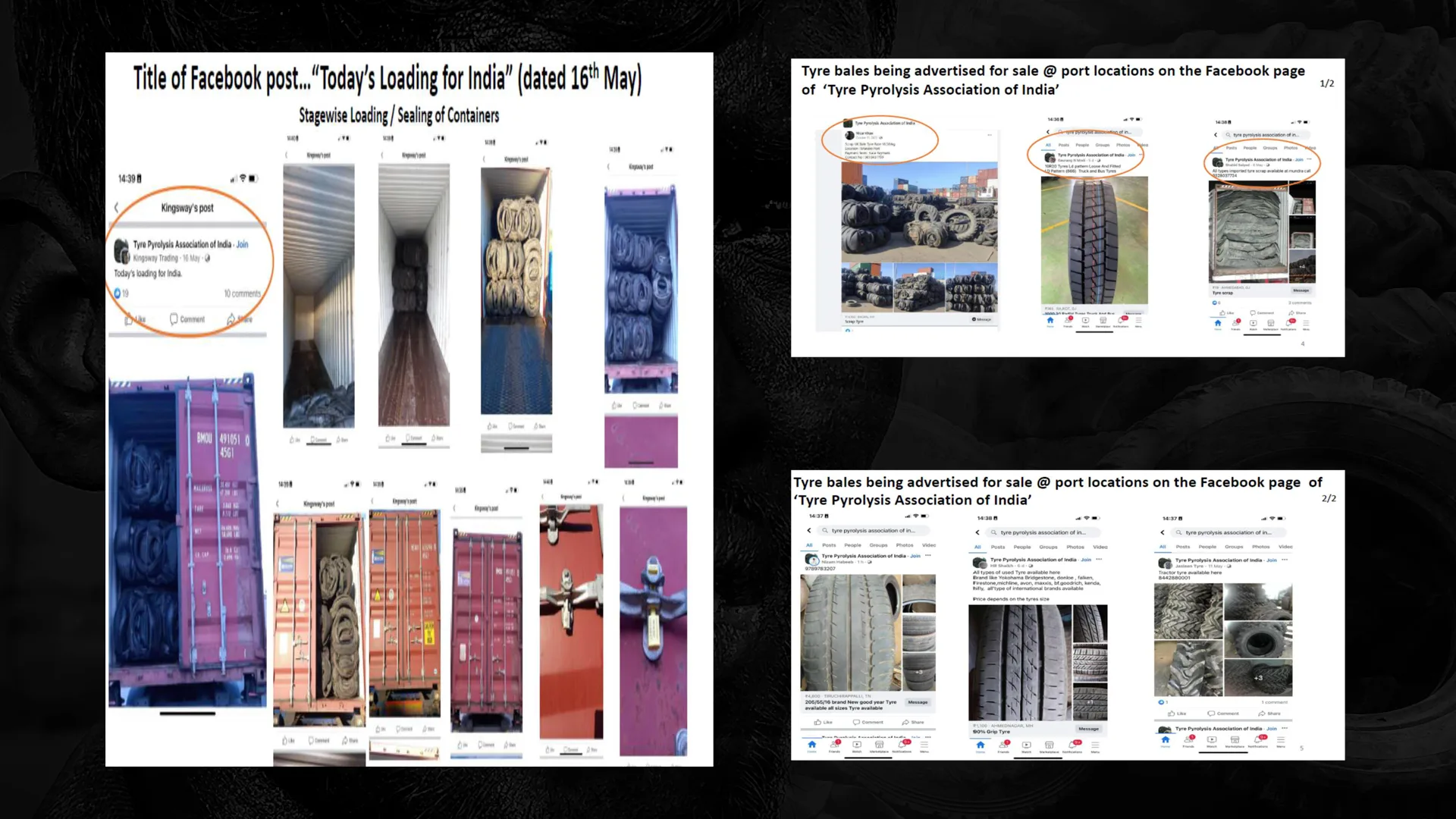

From across the oceans, scrap tyres arrive in enormous, tightly bound cubes known as ‘bales.’ These rubber blocks are shipped into India through three major sea routes; Gujarat, Mumbai and Chennai.

According to the Indian government’s data, over 70% of India’s imported waste tyres (in the name of waste rubber) enter through the major ports.

At the docks, they arrive daily—stacked in towering, soot-black mounds. On paper, they are meant for recycling but, in reality, they follow a darker trail. Once unloaded, the tyres are sorted into two categories. The first batch—those in relatively good condition—is quietly sold to second-hand tyre traders for refitting. These tyres will soon find their way back onto Indian roads.

The second batch, the damaged and unusable ones, is meant for recycling. But instead they’re often sold off to illegal or loosely regulated pyrolysis plants across states like Madhya Pradesh.

The Reporters’ Collective visited various factories, spoke to those entrenched in the business—second-hand tyre dealers, recyclers, plant owners, transporters, truck drivers, and experts.

A tyre trader from Madhya Pradesh’s Indore explained the operation. “When the bales arrive at the port, we get inputs with photos. We buy the tyres based on our requirements. The importer even holds an auction to sell them at higher prices. Around 30% are good enough to be refitted into vehicles. These fetch a good profit,” he said. “From the remaining 70%, we sort out tyres for remoulding that can be fixed in workshops and can be sold as second-hand tyres. The remaining goes straight to pyrolysis plants.”

Deals are struck in hushed tones. Transactions happen through WhatsApp groups, Telegram channels, and shady networks that operate after dark. “We mostly handle transactions in cash,” said a buyer from Morena.

Under the cover of night, and with help from local enablers, the tyres are quietly loaded onto trucks and disappear. Their destination: pyrolysis units and roadside workshops like those operating in Lohgarh, Madhya Pradesh. These plants, however, are only allowed to combust Indian tyres.

The Collective found that traders from Indore and Bhopal have set up discreet warehouses along national highways. Large trucks carrying the imported tyres are unloaded unnoticed. Later, the tyre stocks are transported in smaller loading vehicles, either for remoulding, shredding, or direct dispatch to hidden facilities doing pyrolysis, sometimes even back to Gujarat.

From there, the trail becomes harder to follow. Meanwhile, the official paperwork tells a completely different story.

According to a UK-based NGO's investigation, and documents filed by importers, the tyres are being sent to certified recycling facilities. Everything looks legal. But in practice, the tyres rarely, if ever, reach these authorised plants.

“Under the Hazardous Waste Rules 2016, pyrolysis units are no longer permitted to import scrap tyres,” said a senior official of the State Pollution Control Board. “Still, during recent field visits, we found imported waste tyres at some plants which were either served compliance notices or ordered closure."

The signs to spot the imported tyres are easy. He explained, “Imported tyres are tied differently, cut in specific ways, and carry identifiable foreign brand names like Goodyear, Apollo, Bridgestone, Dunlop, etc.”

While Vijay Ahirwar, former director of Madhya Pradesh Pollution Control Board, reiterates that the state pollution control board reserves rights to issue closure of the factory under Water Act 1974 and Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981 in case of negligence or non-compliance with the Standard Operating Procedure (SoP) upon inspection. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) issues the SoP to regulate the tyre recycling plants including TPOs.

According to him, it's nearly impossible to run pyrolysis plants without strong financial and political backing. “But many of such factories faced closure for violating the norms despite muscle power and political patronage.”

The Collective reached out to Ashok Barnwal, Additional Chief Secretary, Environment Department and Director General, Environmental Planning & Co-ordination Organisation (EPCO), Madhya Pradesh, questioning the functioning of unregulated TPO plants operating across the state.

“The Department and the Pollution Control Board acts upon every complaint and ensures compliance,” he said, adding that lately half a dozen factories were shut owing to non-compliance including three in Morena. They were only allowed to operate after compliance."

Behind the scenes, it’s a business worth crores. On the surface, it's all clean—paperwork aligned, forms filled, rules seemingly followed. But just beneath lies a black economy of burning rubber, corrupted systems, and a choking truth.

India’s Waste Tyre Conundrum

In 2024-25, India’s total domestic tyre production stands at 42 lakh metric tonnes. Of this, 25 LMT is absorbed for the domestic market along with 2 lakh LMT of inner tubes and flaps, while 15 LMT was exported.

India itself generates close to 25 lakh metric tonne units of end of life tyres annually, says Rahul Vachaspati, executive director, Automotive Tyre Manufacturers Association (ATMA), emphasizing that the current recycling infrastructure, largely comprising batch pyrolysis units, needs to be upgraded.

“While India struggles with its own tyre waste, the country imported over 18 lakh metric tonnes of waste tyres last year - mainly from the UK, the USA, Germany, Italy, the UAE, and Australia. They’re not recycled in proper facilities—they end up in these TPO recycling plants, fueling a crisis like Lohgarh.” said Rahul Vachaspati, executive director, ATMA.

ATMA is the apex industry body for tyre manufacturing. It also warned that the number of waste tyres in the Indian market far exceeded the country’s annual recycling capacity. In a letter to the Ministry of Commerce in March 2025, it wrote that these imports were “overburdening India’s fragile recycling infrastructure” and increasing pollution levels. It urged the government to ban the import of waste tyres.

In 2024, India recycled a total 30 lakh metric tonne waste tyres. Out of this, 16 LMT were generated domestically, while 14 LMT were imported. Although India’s current capacity to recycle waste tyres is 28.76 lakh metric tonnes. Vachaspati pointed out that “combining the number of domestic and imported tyres for recycling in 2024–25, India had a stock of 43 lakh metric tonnes of waste tyres - much higher than its capacity.”

According to NITI Aayog's ‘Waste Tyre Economy in India’ report 2026, the country has an estimated 851 recyclers and only 552 were authorized. The remaining 299 unauthorised recyclers are incinerating over 9 lakh metric tonnes of waste tyre.

The report admits, “...approximately 300 unauthorised recyclers, and the total unauthorized capacity rises to about 9 LMT, revealing a significant portion of the recycling landscape that operates outside regulatory oversight. Informal players often rely on low-cost, non-compliant batch pyrolysis units that lack proper environmental safeguards.”

The rise in import was already predicted by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in September 2019 order when it called for a curb on the import of waste tyres, “... to ensure that India does not become a dump yard for highly polluting hazardous waste material from other countries and also to ensure that health of the workers involved in the process is duly safeguarded.”

What the NGT Court anticipated in 2019 turned true. In 2022, India banned the import of Waste Pneumatic Tyres for pyrolysis. The factories such as those in Lohgarh are only allowed to process Indian tyres.

But, in March 2025, a UK-based investigation busted this glaring violation. The report outlined that a GPS-tracked shipment of waste tyres left the UK, supposedly for recycling by Nine Corporation, India’s second-largest tyre importer. The tyres landed at Mundra Port, Gujarat, after eight weeks. But they never went to the company’s Gujarat plant. The agency tracked that the waste tyres are ending up in Lohgarh and other such plants across India.

The UK investigation held that UK tyres are ending up in these Indian pyrolysis plants, despite legitimate official paperwork stating they are headed for legal Indian recycling centres. They found that some 70% of tyres imported from the UK and the rest of the world end up in makeshift industrial plants, where they are incinerated.

The UK report also revealed that two tyre bales, sent in an earlier consignment in 2023 arrived in Haryana – a small state which has 112 TPO plants.

There are 736 pyrolysis factories across 22 states. Among those, Uttar Pradesh has the highest 161 TPO plants, followed by 112 plants in Haryana, and 103 in Maharashtra, according to the Central Pollution Control Board report submitted to the National Green Tribunal in January 2024.

“There are at least 1,500 pyrolysis plants operating in India,” said Sanjay Upadhyay, a Delhi-based environmental lawyer whose petition at the NGT Court forced the CPCB to buckle up these factory owners in 2019. “The monitoring authorities often hide the actual number of plants as most of these function in the shadows, protected by local officials and politicians for financial gains.”

Why Surge in Import—The EPR credits?

The Industry expert believes that India’s waste tyre crisis is accelerated by the policy that was introduced to regulate and manage waste tyre recycling in a manner which shall protect health and environment.

At a time when India banned the import of waste tyres for pyrolysis, it also brought waste tyres under the Extended Producers Responsibility (EPR) framework in 2022 obligating the tyre producers to dispose of their end-of-life tyres 100% by 2024-25 scientifically. It means the producers have to dispose of the same amount of tyres they manufacture every year. The EPR shifts responsibility of the waste tyres management from government to the producers.

“Since the producers didn’t have their own recycling infrastructure when the EPR was enacted, many roped in government-authorised recyclers to meet their obligations,” said Satish Goyal, president of the Tyre & Rubber Recyclers Association of India (TRRAI).

The policy allows recyclers to dispose of waste tyres and upload them on the Central Pollution Control Board’s website that will review and issue EPR credit certificates. These credits can be purchased by the producers. “Recyclers generate EPR credits on the behalf of producers and sell it to the producers to meet the EPR compliance of end-of-life-cycle tyres.”

But like many regulations in India, the lack of monitoring and compliance by the pollution watchdog agencies became a loophole.

“Before the EPR regime, recyclers earned revenue only from end products such as oil, char, and steel. After EPR was introduced, however, many authorised recyclers began importing waste tyres in bulk and diverting them to TPO plants, exploiting weak monitoring from ports to processing facilities,” said Saumitra Jaiswal, a Delhi-based lawyer pursuing petitions to regulate TPO plants in the NGT.

He pointed out, “Because EPR credits are awarded based on the volume of tyres processed rather than environmental performance, burning imported tyres in substandard facilities became highly profitable. This has driven a fivefold rise in scrap rubber imports since EPR credits were introduced.

Industry experts and a UK NGO’s report suggest that importers or traders are exploiting the loopholes and the absence of a monitoring mechanism in the policy diverting imported tyres to TPO plants to generate EPR credits.

The Environment Ministry reports that only 296 of 736 TPO recycling plants are currently registered on its portal.

A Bhopal-based tyre trader Guddu Khan noted that imported waste tyres cost ₹2–5 per kg, far cheaper than domestic tyres priced at ₹20–25 per kg in the Gwalior–Chambal region. Imported tyres are more easily available than domestic ones as India doesn’t have waste tyre collection centres. Besides, imported tyres generate more profit than the domestic tyres.

“They generate EPR credits burning imported tyres but masked it as domestic, then sell those credits to tyre producers,” explained Imtiaz Ali, an environmentalist and waste management expert from Madhya Pradesh. “The more they burn, the more they earn.”

Inside the Plant: Toxic Truths

Behind the locked gates of tyre pyrolysis factories in Lohgarh (Morena) and Kalapipal (Shahpur district), The Reporters’ Collective uncovered a grim reality—one where environmental norms are flouted, and human lives are quietly traded for profit.

Labourers, earning Rs 500-800 a day, fed tyres into blazing furnaces, their skin slick with soot and sweat. Without gloves, masks, or helmets, they work under dangerously unsafe conditions. “All we get is Surf or Rin soap to wash up,” said Rajesh Kumar, 42, a labourer from Agra, who was lured here for slightly higher wages to support his family of four.

“We feel suffocated. Many vomit when the boiler gates open,” Rajesh shared his experience. He lives in a makeshift shelter within the factory grounds. “No one can survive this for more than a few months. Workers rotate every 30 days.”

Inside these units, nearly every condition mandated by the 2025 SOP is being violated, says Professor Mawai, who has been fighting for the closure of the plants for over a decade.

“We have documented over a dozen cancer deaths here in the last two years. Many more people are showing similar symptoms. Respiratory illness is as common as fever,” he says, waving the latest air and water quality reports. “Yet, the factory owners enjoy the patronage of a heavyweight politician and immunity from the watchdog agencies.”

According to environmentalist Rashid Noor Khan, this violates Rule 4(6)(b) of the Hazardous Waste Rules, which mandates protective gear and training for workers. But instead of masks or goggles, labourers are handed pieces of jaggery. “They say it helps push carbon dust stuck in your windpipe into your stomach,” one worker said grimly.

They speak of black carbon clogging their pores, making it impossible to sweat, and of coughing up soot from their lungs. “Prolonged exposure without protection can lead to acute lung damage,” warned environmental expert Sagar Dhara.

Despite growing complaints, the state and local administration remain largely indifferent. “It’s as if the factories are invisible to the authorities,” Mawai said.

Between 2019 and 2025, the Madhya Pradesh Pollution Control Board received complaints against 18 such plants. Some of them were issued closure notices but after renewed complaints in June 2025, an SIT (Special Investigation Team) was formed that gave clean chit to all the factories.

“Based on their findings, three plants—Pitambra Industries, Anjali Biofuels, and RV Green—were issued closure notices. All were reopened after the factories complied with the existing laws,” said Rishi Singh Sengar, regional PCB officer in Gwalior. “Nine more were warned to comply with the SOP.”

He maintained that air quality levels were within limits and claimed the use of wood was only for ignition but declined to address the allegations of imported tyres being illegally processed.

Locals, however, remain unconvinced. “The water is contaminated 300 feet deep,” claimed Sanju Pahalwan, a national wrestler. “You can see black carbon particles with the naked eye.”

Winning many medals for Madhya Pradesh, Sanju has been fighting for the closure of the factories—filing complaints, blocking highways and highlighting the violation of SOP inside the factories through social media. “Every time we protest, inspections are staged,” he said. “The owners get tipped off, they shut operations, clean up, and prepare fake records. It’s all eyewash.”

Still, not all view the plants as villains. It is because for many there is just no other way to earn their livelihood. Dheeraj Gujjar, 22, lives just meters from one of the factories and proudly displays his ID badge. “I earn Rs 15,000-20,000 a month. It helps feed my family,” he said. “Most of us are illiterate. What options do we have to make a living?”

Even Dheeraj concedes that the water is worsening. “Every year, it gets darker,” he admitted, gesturing to the pond behind his village. Under the moonlight, its surface shimmers—not with purity, but with oil-slick waste. A poisoned mirror, reflecting a community’s quiet compromise.

.avif)