New Delhi and Patna: Breaching its own guidelines and previous practices, the Election Commission of India (ECI) did not deploy the specialised software programs at its disposal to identify potential fraud, duplicates, and incorrect entries in the finalised Bihar voter list.

This was confirmed to The Reporters’ Collective by a top official of the Election Commission of India (ECI) in Delhi and four Electoral Registration Officers (EROs) in Bihar.

They confirmed that ECI had neither given state officials access to the software to detect frauds and duplicates on their own, nor had ECI carried out this exercise at the central database level and shared lists with them for manual verification during the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the voter roll in Bihar.

The ECI had used this software—at its discretion on occasions—to remove duplicates over the years, including for the 2024 Parliamentary elections.

The result of ECI not deploying it in Bihar SIR? Our previous report revealed that the final Bihar voter roll for all 243 assembly constituencies now holds 14.35 lakh suspect duplicate entries. Of these, 3.4 lakh entries are exact matches on all three demographic parameters: name, relative’s name, and age.

More than 1.32 crore voters of different families, castes, and communities were bundled and registered in groups of 20 or more at dubious and fictitious addresses in the final Bihar list. There are at least 20 households where more than 650 people have been clubbed and registered wrongly.

These large-scale errors and possible frauds would have been easy to detect had the ECI run its de-duplication software on the draft voter roll before finalising it.

We emailed questions to the ECI and its top official in Bihar, the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO). Neither of them replied to us. When one of us met the CEO in person in Patna, he refused to speak on record and asked the reporter to leave. His parting words were laced with intimidation. He said, “The Model Code of Conduct is being implemented in the state. Consider this before reporting.”

The Model Code of Conduct does not bar journalists from reporting facts or asking questions of ECI.

The Missing Module

In 2016, the then Chief Election Commissioner, Dr Nasim Zaidi, announced the National Electoral Roll Purification scheme—NERP 2016. It was launched by the Commission to improve the fidelity of the rolls by “effective use of information and technologies.” As part of this exercise, the national electoral roll data were processed using an automated method or machine learning to find demographically similar entries for local election officials to vet. ECI had thus begun development and deployment of this automated method to find duplicate entries on voter rolls.

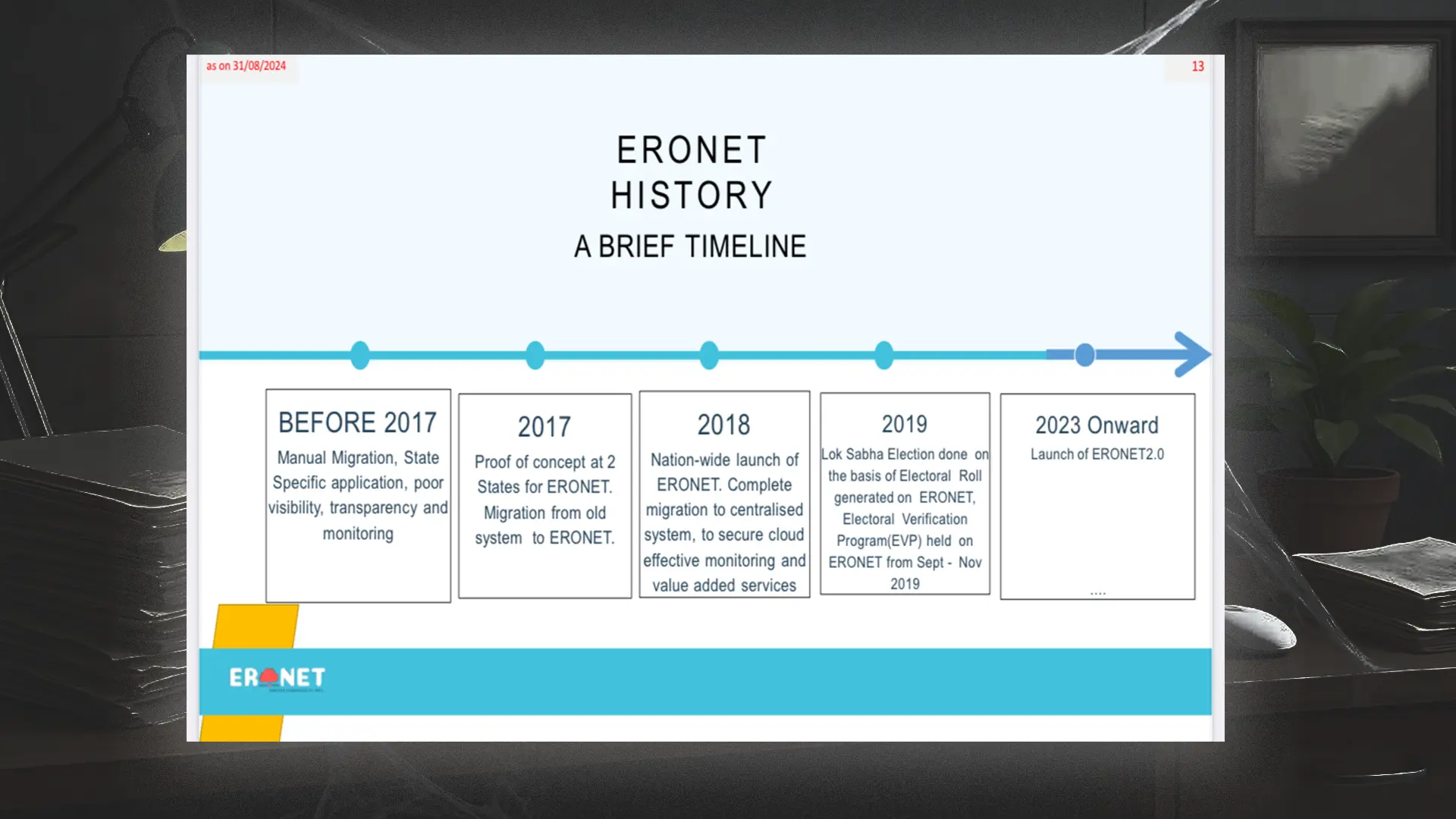

By 2018, this ability to find suspect duplicate entries via machine learning was in the hands of state election officials as well, incorporated into ECI’s IT interface for Electoral Officers, called ERONET.

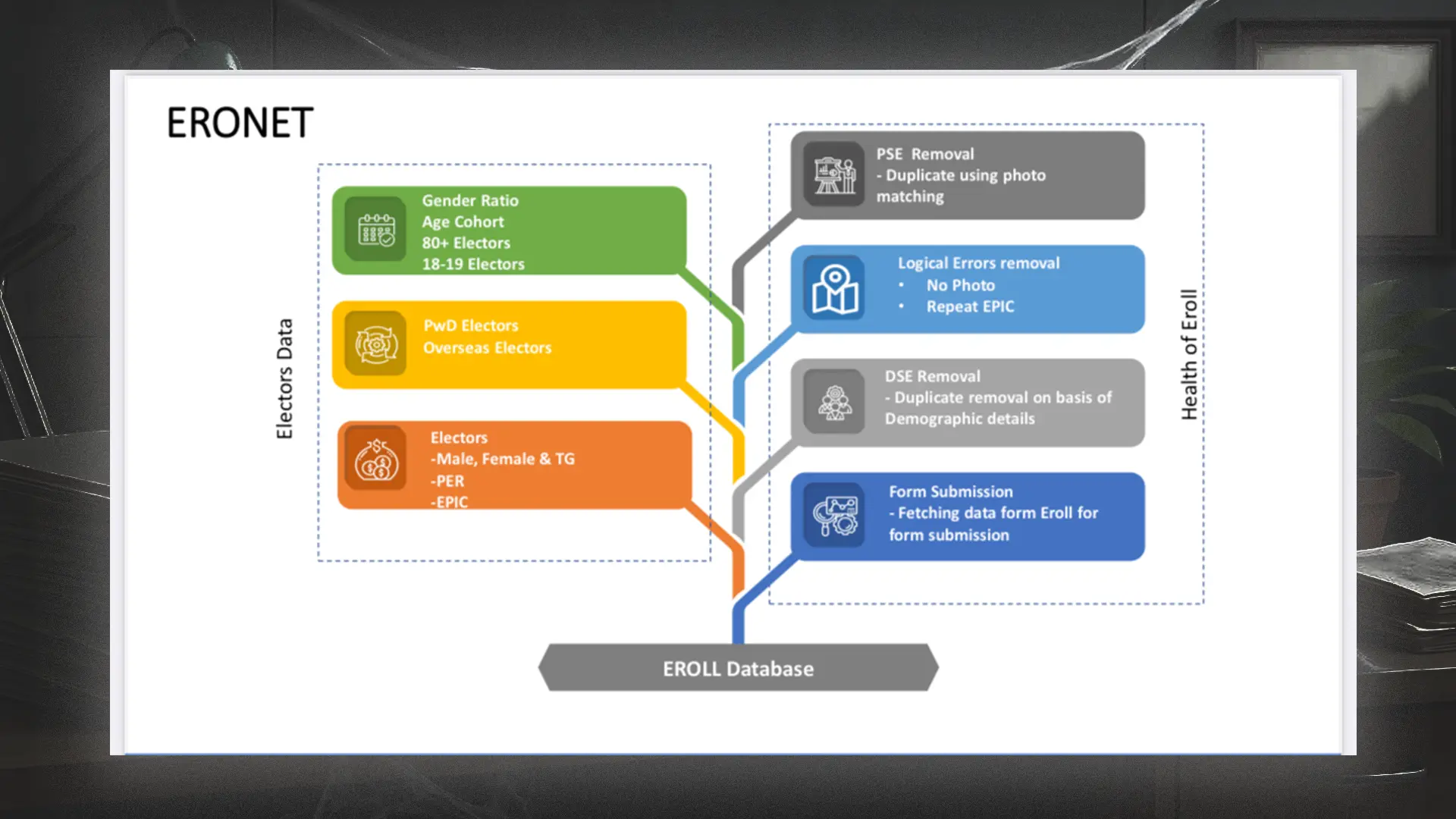

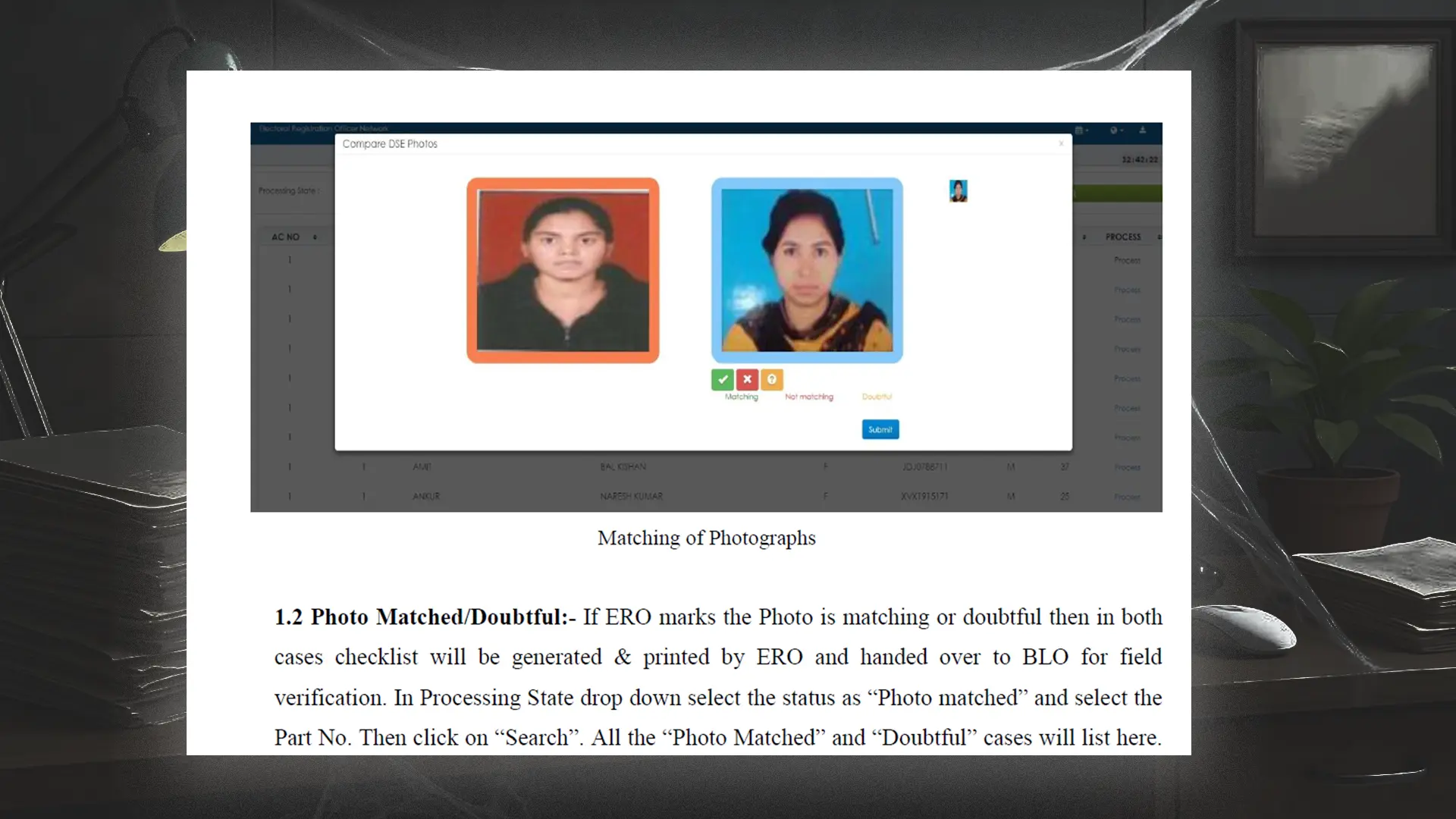

The Election Commission’s presentations on ERONET reveal that this application can identify suspect entries that are demographically similar. In other words, it detects similarities in names, names of relatives, addresses, and ages to identify suspect duplicates and fraud. It can also match photographs on Voter IDs (called EPIC) to detect potential fraud and duplicates.

Media reports from the time cite ECI claiming the software was then used to vet duplicate entries in several state voter rolls, including Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, and Mizoram.

The Process of Removing Duplicates and Suspects

The software detects possible duplicates. Such duplicates can be found within a constituency, of which a single ERO is in charge. Or the duplicates can be registered across multiple constituencies within a state. The third type—often in the case of migrants—involves multiple cards held by a person or fraudulent cards made of the same person in different states.

The detection of duplicates within a constituency can be done by providing the ERO with access to the de-duplication software for limited deployment on the constituency database.

The detection of cross-constituency duplicates can be carried out by handing over rights to run the software to the state Chief Electoral Officer’s team, which has access to state-wide lists.

For inter-state migrants, duplicates, and possible frauds, the ECI has to run the software on the countrywide database to detect those holding multiple voter IDs across state boundaries.

Once the list of possible duplicates and frauds is detected, the EROs are required to send notice to the suspect voters in their domain. After a hearing, they are to determine if the person has voting rights or not in that constituency.

The process requires time, particularly for suspects across constituencies and states. It has not been done methodically and widely across the country for this reason.

As recently as March 2025, media reports, citing unnamed sources in the ECI, claimed that duplicates would be removed in mission mode.

But something else happened. We could not ascertain when exactly this transpired, but the access to the software for state ECI officials was made unavailable.

During past years, on different occasions, officials in the states said that ECI would share lists of potential duplicates at its discretion and ask state officials to verify and delete duplicates. It was done at the ECI Headquarters’ discretion and request.

“ERONET’s deduplication module is currently only accessed by ECI in Delhi. Only they have access to voter rolls for all states and can thus authoritatively identify voters with duplicate entries. In the current protocol, ECI shares lists of suspect duplicates with state CEOs when it wishes to check and verify, per their discretion,” a deputy Chief Electoral Officer in one of the northern states told The Reporters’ Collective.

No Software For Bihar

The Bihar SIR was announced with much chest-thumping by the ECI, claiming the use of technology and its vast army of constituency-level workers and volunteers would detect duplicates, working migrants, illegal migrants, and others to clean the voter roll.

In a sprint of over 30 days, all voters were asked to provide documentary evidence of their rights afresh. Faced with chaos, anger, and confusion, halfway through, the ECI ordered the BLOs to merely collect the signed enumeration forms and let people file their documentary proofs later.

The draft list was generated by the ECI on the basis of these signed enumeration forms.

At this point, the de-duplication software should have been deployed by ECI to identify potential duplicates, fraud, and errors.

The ECI did not.

In the draft list, we found 5.56 lakh suspect duplicates in 142 assembly constituencies. When we analysed a single assembly constituency, Valmikinagar, for duplicates from neighbouring Uttar Pradesh, we found 5,000 cases of suspect duplication here as well.

At the time, the CEO of Bihar responded to our reportage on social media to claim that we had found these errors through computer programmes. This is correct. We had done what the ECI could have with its software. The CEO of Bihar said that it was only a draft voter list and any errors would be removed before finalising it.

We called more than 15 constituency-level EROs of Bihar to understand what actually transpired during the two months between the publication of the draft list and the final one.

They were mostly busy just collecting the documents for the enumeration forms that had been filled and then trying to respond to the amendments people had proposed to the voter list. During the Special Intensive Revision in Bihar, ECI made no attempts to check for duplicates on voter rolls at all, as we confirmed at several levels.

A top official at ECI who spoke with us said, “We did not touch deduplication during SIR. Mostly our focus was on document collection.”

Four EROs in Bihar spoke to us on the condition of anonymity. EROs are top officials of an assembly constituency who preside over the electoral process at that level. They too confirmed that for this revision exercise, they had not received any list of voters from the top that were identified as suspected duplicate voters, warranting a quasi-judicial check.

“Our booth-level officers made manual checks for the thousand or so voters in their booths. Once they identified duplicates, those cases would be formally vetted before Form 7s are filled for the deletion of confirmed cases,” one of them told us.

“I convened block meetings so that BLOs from nearby booths could meet and exchange notes—to catch voters who might have inadvertently enrolled on nearby booths as well,” another said.

They did not get any lists from the CEO Bihar’s office or the ECI headquarters to verify for duplicates and other errors, they all said. “We did not receive any list of suspect duplicates from the top. That was not the purpose of this SIR; the purpose of this exercise was to establish citizenship,” one of them specifically mentioned.

They had got such lists during the preparation of the voter list for the 2024 General Elections, one ERO said.

“In 2024, the Bihar CEO had shared a list of 5,000 to 7,000 entries with every constituency in Bihar. These were physically or demographically similar entries. Those suspect duplicates were checked at the time,” he added.

“Even if the state officials had been sent lists of lakhs of potential duplicate voters, it would be unfair to expect them to hold formal inquiries in all the cases in the short span of 30 days. It is just not possible,” said a deputy CEO from another northern state, explaining why the three-month period was just not adequate for a necessary cleanup of the voter roll, whether in Bihar or in any other part of the country.

Which is why it is no surprise that 32-year-old Mithilesh Kumar from Jale Assembly constituency finds himself on the voter rolls twice. This is even though The Collective went on the ground to profile his case of duplication and informed both BLOs of the error occurring well within the verification period.

Voters with the same credentials and even the same photographs have now been detected at large scales in this hastily generated final list. Many are holding more than two voter IDs.

A Rough Encounter with CEO Bihar

After we had corroborated evidence from multiple sources, one of us (Vishnu Narayan) approached the CEO Bihar, Vinod Singh Gunjiyal, in person to pose questions on the lack of de-duplication.

We made several attempts over two days to meet him at his office and waited for hours to do so. We were asked to meet junior officials who are not permitted to speak to the media. Quite naturally, they refused to answer our questions.

Then, we sent a formal questionnaire to the CEO and the ECI Headquarters. Within minutes, Vishnu was called to meet the CEO at his office in Patna.

Upon eventually meeting him, our first question was whether the ERONET software for marking duplicates in the voter list was accessible to the CEO or ERO in Bihar. To which he replied, “We cannot share this information with you.”

In return, he asked us whether we intended to quote him on record. We said, “Yes.” Gunjiyal asked us not to record the exchange. We asked him another question: “The Election Commission of India often shares a list of duplicates to the State Election Commission to be verified. During SIR, has ECI sent such a list?”

He replied, “There is a legal procedure in place for any such process—the Supreme Court is hearing the entire matter, and we are presenting everything there, and you can leave.”

These were Gunjiyal’s parting words as we left his office: “The Model Code of Conduct is being implemented in the state. Consider this before reporting.”

The Model Code of Conduct is a set of protocols issued by the election authorities to political parties and candidates to allow ECI to police their behaviour. The rules do not prevent journalists from carrying out legitimate journalistic reporting.

No formal responses have been shared by the CEO Bihar or the ECI so far. Our story will be updated if they are received.

.avif)