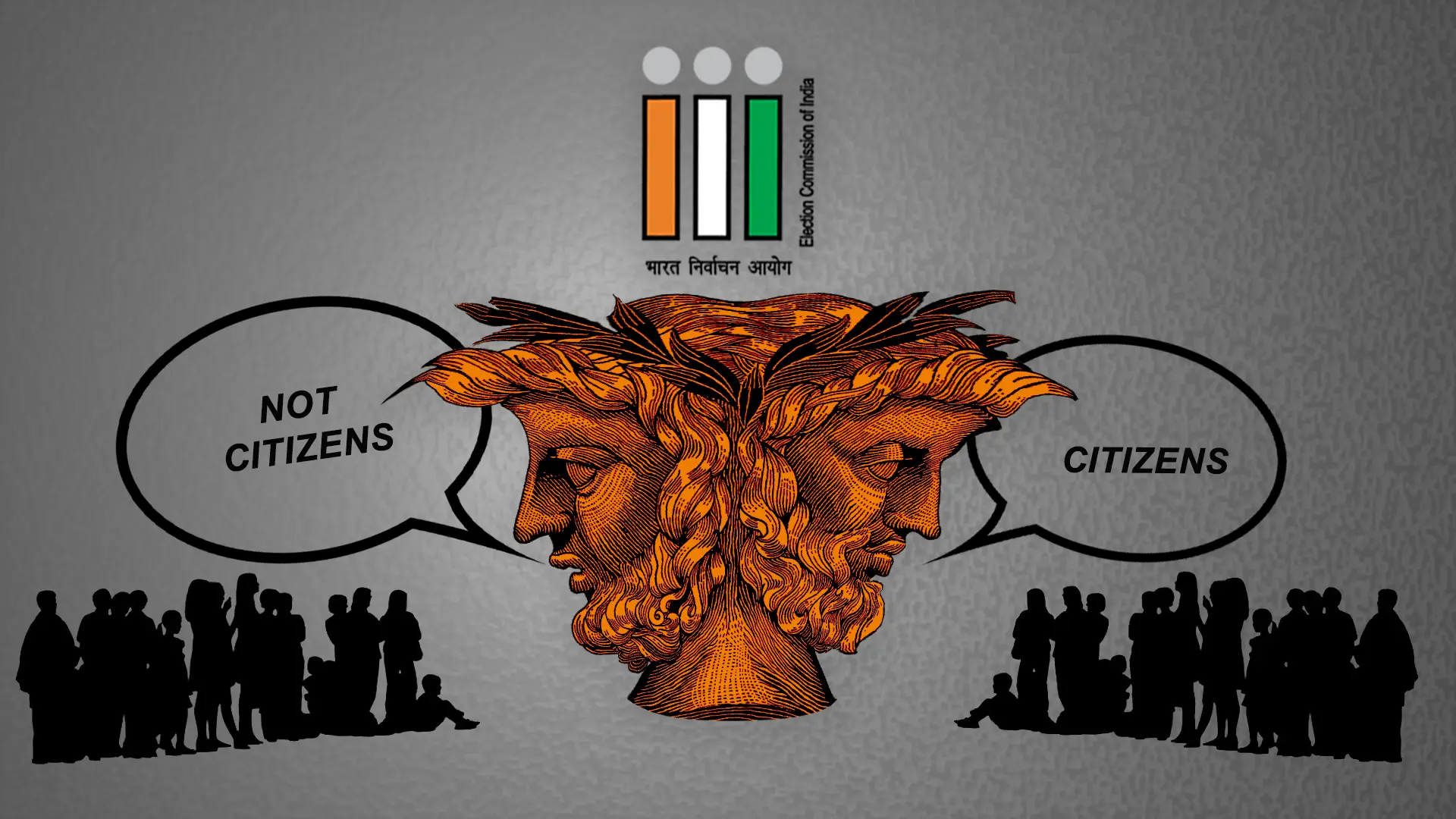

New Delhi: The Election Commission of India (ECI) has reasserted its power to verify if a person is a citizen or not while undertaking a country-wide, unprecedented voter registration exercise, which it has termed “Special Intensive Revision” of the electoral roll.

In a counter-affidavit filed before the Supreme Court, it has said, “The ECl is fully competent to require a person claiming citizenship by birth to produce relevant documents for inclusion in the electoral roll.”

The burden on proving their citizenship with documentary proof during the unprecedented voter registration, now in Bihar and next in the rest of India, lies on the people it has said and added that the Electoral Registration Officer and the Chief Electoral Officer - local officers appointed for election purposes – will have the power to verify peoples’ citizenship documents during the drive.

The ECI’s affidavit comes in response to a challenge by several opposition parties and others to hold a country-wide voter registration from scratch in an unprecedented manner, starting with Bihar, which it ordered on June 24, 2025, calling it an SIR, a term not found in either the regulations or the manuals governing voter registration.

The petitioners have questioned the hurried nature and the process by which ECI has ordered the revision of voter lists in Bihar just before the due assembly elections. They have also questioned the curtailed and differentiated list of documents that the ECI has mandated as proof from different sets of people in Bihar to prove their right to vote and citizenship. ECI has stood its ground on all counts against the petitioners.

The Commission said, “ECI is vested with the powers to scrutinize the eligibility of a person with respect to his/her entitlement to be registered as a voter. Section 16 of the Representation of People Act, 1950 expressly alludes to citizenship as a qualification.”

It has stuck to its guns that existing Electors Photo Identity Card (EPIC) cards issued up to January 2025, Aadhaar and ration cards would not be used for voter registration, and the listed 11 documents would be. Except, for voters registered up to 2003, and their children would need to provide proof of 2003 enrolment.

The Commission has claimed that the Union government’s exclusive powers over the determination of citizenship are limited to the occasion when an Indian citizen has voluntarily acquired citizenship of another country. In all other cases, authorities, such as the ECI, can also verify citizenship, the commission has said.

“It is only for this limited purpose that the exclusive jurisdiction has been vested in the Central Government, to the exclusion of all other authorities. Other aspects related to citizenship can be inquired into by other relevant authorities for their purposes, including those who are constitutionally obligated to do so, i.e., the ECI.”

Going a step further to assert its authority, the ECI has said a law passed by the Parliament too cannot take away its power to verify citizenship, as that is provided in the constitution.

ECI has argued that it is not in violation of the Constitution to require, through the enumeration form that for some voters (born between July 1987 and December 2004) it has asked “the elector to provide not just his/her documents to prove his/her citizenship, but also documentary evidence of citizenships of his/her mother or/ and father, failing which his/her name would not be added to the draft electoral roll and can be deleted from the same.”

It claims the law does not lay down what documents are sufficient to prove their citizenship, so in the case of voter registration, it has the power to prescribe what proof will be required from citizens.

Under the law, one is considered an Indian citizen if she is born in India and fall in one of the three categories below:

- Born between 26th January 1950 and 1st July 1987: Are citizen irrespective of the nationality of parents.

- Born between 1st July 1987 and 3rd December 2004: One parent should have been an Indian citizen when the person was born.

- Born on or after 3rd December 2004: Both parents must be Indian citizens; or if only one parent is a citizen, then the other is not an illegal immigrant.

Although the ECI has emphasised that district level officials have to verify the citizenship of the people, their identity and their ordinary place of stay to be eligible to vote, it has passed the buck for the situation that the officials in their quasi-judicial review decide that a person could not prove their citizenship. ECI has said, “It is reiterated that determination of non-eligibility of anyone under Article 326 will not lead to cancellation of citizenship.”

In the law, ECI admits, cancellation of Indian citizenship is a process overseen by the Union government for someone voluntarily taking up another country’s citizenship.

Burden of Citizenship Lies on Citizens

The ECI states that it is the people’s responsibility to prove their citizenship with documentary evidence, as asked for during the revision of the electoral roll across the country.

It has said that the Electoral Registration Officer and the Chief Electoral Officer at the district level hold the powers to ascertain the citizenship of people while registering them afresh into the voter list.

“That in so far as the burden to prove citizenship is concerned, it is submitted that the necessary documents required to establish citizenship are within the special knowledge of the individual claiming to be a citizen of India. Given the nature of this evidence and the fact that such evidence should/ought to be within the personal knowledge of the individual concerned and not of the authorities of the State, it is incumbent on the said individual to provide such proof.”

The ECI cites, besides others, Supreme Court judgements in the controversial Assam case about identification, detection and deportation of migrants held to be ‘illegal’. Triggered from the ad-hocism in the citizenship drive in the state, the incumbent BJP government in Assam has turned a historical issue of mass migration from neighbouring Bangladesh into a communal issue by specifically targeting the Muslim population in its campaigns.

Confusion on Ground and in ECI Stance

ECI had initially given citizens of Bihar 30 days to submit enumeration forms and required different classes of citizens to provide different kinds of proofs in support of their citizenship and right to vote. Based on this, a draft list of voters was to be prepared. People would get another 30 days to contest if they found their names missing or wrongly put in the draft list.

Early days into the exercise, with booth-level officers facing immense difficulty in obtaining the documents from citizens during the door-to-door drive, the ECI changed tack. It said voters could do with just providing the enumeration forms in the first 30 days of the door-to-door exercise. They would subsequently have to go and plead before the ERO and the CEO with documentary proof to confirm their rights.

This led to a large number of enumeration forms being submitted without documentary proof, ground reports have shown.

In its affidavit to the Supreme Court, the ECI has claimed that 94.68% of forms had been collected. Neither did ECI disclose that it had changed its procedure midway, nor did it inform the court of how many of these enumeration forms had been submitted without documentary evidence, which citizens would now have to approach the authorities over a short span of 30 days.

The ECI has said that parties have previously complained of mismanagement by booth-level officials as well as district officials during voter list revisions that have been undertaken over longer durations than the SIR. But, ironically, it has used this argument to say that the SIR it has now undertaken in a much shorter period will be more exhaustive because it has deputed volunteers and staff at scale.

At the same time, in its affidavit, the ECI says it has asked the political parties, besides officials, to help it carry out the exercise. Its affidavit reads, “The list of electors who have not filled their Enumeration Forms has been shared with all the recognised political parties to seek their assistance in reaching out to all.”

ECI’s numbers in Bihar show that the BJP leads the pack for volunteers or booth-level agents who will help it carry out the revision. BJP has 52,698 booth-level agents in Bihar, followed by Rashtriya Janata Dal with 47,506 agents, and Janata Dal with 35,799 agents. Congress trails the pack with 16,676 booth-level agents.

The Supreme Court is set to hear the case next on July 28.

Link to our investigations on SIR can be found here and here.

.avif)