New Delhi: On June 11 2024, Tabrej Alam from Meghua village in East Champaran district of Bihar, submitted a form to the designated booth-level officer to delete Hussain Sheikh’s name from the electoral roll. Hussain had passed away. By November, election officials verified Tabrej’s identity and his claim. By January 2025, Hussain’s name was deleted on Tabrej’s request from the voter list of Bihar.

Five months later, the same 37-year-old Tabrej was forced by the Election Commission of India to prove with documentary evidence that he exists, is a citizen of India and resides regularly enough in his village to have the right to vote in the upcoming Bihar assembly elections.

There are millions of citizens in Bihar like Tabrej who may have voted in one or all of the last five general elections and five assembly elections, but now have to present documentary evidence rather quickly to validate their right to vote. And, if they are unable to, they could stand as people of doubtful citizenship in the eyes of the law.

This is the consequence of a sudden decision of the Election Commission of India on June 24 to completely revamp the electoral rolls in Bihar, ordering what it defines as a Special Intensive Revision.

The decision invalidates millions of voters registered since 2003 unless they can prove their citizenship, identity and normal place of residence afresh, and do so very soon. All of them now have to provide evidence afresh of their right to vote. Many who enrolled before 2003 will also have to show proof of their enrolment.

The Reporters’ Collective reviewed records to find that the ECI’s decision was a sudden U-turn that hit the state election machinery by shock. We found evidence that, till days before the ECI’s order on June 24, officials in the state had been regularly updating the electoral rolls using legally mandated and practised methods.

In fact, between June 2024 and January 2025, the state election machinery had completed a revision of the electoral rolls, called the Special Summary Revision 2025, shows electronic records maintained by the Bihar Chief Electoral Officer.

This runs contrary to the ECI’s allusions that Bihar’s existing electoral database was in such a bad shape that it needed a full revamp.

The evidence we reviewed shows that contrary to ECI’s claims, even in the month of June 2025, days before the decision, ECI and its officials in Bihar had accepted the existing electoral roll finalised for the Parliamentary elections in 2024 to be valid. It was using this electoral roll to undertake the regular updation, deletion and addition of voters to it, we found.

We spoke to officials in the Bihar Election Commission office and to two people who have served in the Election Commission of India officially at the highest levels in recent years. Alongside, we spoke to more than a dozen Booth Level Officers in Bihar who are the last-mile government officials in charge of elections and electoral rolls. They all wished to remain anonymous. We are citing portions of their testimonies that we could independently corroborate.

One of the two ex-ECI officers we spoke to said it was the first time that the ECI had undertaken such a “disruptive” exercise, which, without reason, discriminates between voters who were enrolled before 2003 and those after.

“If the ECI is asking all voters registered after 2003 to validate their voting rights with a restrictive list of documentary evidence, ECI is suggesting that a disturbing number of people who voted in the past five Parliamentary elections and the past five state elections (since 2003) were either fraudulent or wrongful. Is that so?” he said.

“If it is, then the entire government apparatus and officials from the highest to the lowest rank involved in the preparation of electoral rolls for years are liable for having either missed or abetted large-scale fraud and gross mistakes over decades. I find it unbelievable,” he added.

“For all practical purposes, entire Bihar’s electoral roll is being prepared de novo at such short notice. The ECI has the power to do what is needed to maintain a clean electoral roll. But in this case, I believe, the discretionary power at its disposal has been used to wrongful ends. This exercise could end up taking away the rights of people to vote and unfairly raise doubts over their citizenship,” the other ex-ECI official added.

We sent questions to the ECI. They are yet to respond. The story will be updated if they do.

What evidence was gathered by the ECI within a few days of June to negate the ongoing updation, the legitimate and just completed Special Summary Revision and updations of the electoral roll of Bihar? The evidence gathered for this report suggests no statewide large anomalies were recorded to trigger a wholesale revision from scratch.

The 30-day exercise of revising the electoral rolls is on in Bihar, as we report. ECI continues to claim it is being done smoothly, and it has not stepped back from its order to undertake this throughout the country.

ECI versus Rules

Lists must be updated to account for deaths, migration, and urbanisation. There are statutory rules defining this exercise. The Registration of Electors Rules of 1960 defines three ways in which electoral rolls can be revised. These are

- An intensive revision - the creation of a voter list from scratch, without any reference to a pre-existing roll with 100 per cent door-to-door verification.

- A summary revision - an annual exercise where booth-level officers invite claims and objections from the public regarding discrepancies in the electoral roll, verify these to publish the final roll.

- A ‘partly summary and partly intensive revision’ - a mix of above two techniques.

- The rules do not define it, but the ECI manual details a fourth type of revision, called the Special Summary Revision, triggered when ECI finds pockets of failure in the routine routes of revision. The ECI records these shortcomings and then notifies the special summary revision.

What the Election Commission has ordered now for Bihar and later for all of India, it has been named as a ‘Special Intensive Revision (SIR)’. The term does not exist and is not defined in the rules governing revision of electoral rolls.

Under the SIR, the ECI has ordered the following:

- Voters registered up to 2003 would have to provide evidence that they were in the rolls of that year.

- Voters above 40, who are missing from the 2003 electoral list, will have to provide documentary proof of their citizenship, identity and residence.

- Voters between the ages of 21 and 40 need to show either their parents’ proof of being enrolled as voters in the 2003 electoral roll, or prove their identity, citizenship, along with either of their parents’ identity and citizenship. They would have been too young to be part of the 2003 electoral roll being used as a base for revision.

- Voters who were born after 2004, less than 21 years of age, would have to either show their parent’s proof of being enrolled as voters in the 2003 voter roll, or prove their identity and citizenship, along with providing documentary proof for the citizenship and identity of both their parents.

Voters have 30 days to provide evidence and another 30 days to contest if their names are deleted or wrongly entered in the database.

There is no precedent of such a revision in Indian electoral history. The last time the ECI commissioned something called an SIR in 2002-2003, it was done over a year-long elaborate process and not a short, hasty three-month process just before elections. As importantly, the 2003 SIR did not discriminate between voters who got enlisted in one period versus those who were recorded at another time, shows ECI’s manuals reviewed by The Collective.

By merely calling it ‘special’, the ECI took the discretionary route to evolve an entirely new enrolment process that treats different citizens differently and demands differing levels of proof from people to get into the new voter list.

In its notification, ECI claims this special drive was necessary because, “The Commission has noted that during the last 20 years significant change in electoral roll has taken place due to additions and deletions on a large scale over this long period. Rapid urbanization and frequent migration of population…have become a regular trend.'

Evidence from the Bihar Election Officer’s records suggests otherwise.

The Just Concluded Special Revision is Now Defunct

Under instructions from ECI, Bihar’s election apparatus had just completed a special summary revision of the electoral rolls, records show. The work began in June 2024 and was underway till November 2024. After the entire elaborate exercise, the finalised list was uploaded as recently as January 2025, again, the ECI records show.

The addition, deletion and changes to this list based on objections and submissions were on-going well into June as the rules require, till days before the ECI suddenly changed track on June 24 and ordered the unprecedented voter list from scratch, records show.

A senior official involved in the Bihar election process said, “After the revision, we are required to assess it for its health on specific parameters, such as projected population to voter ratio, gender ratio, age cohort analysis, polling station-wise abnormal additions or deletions in the past three years. If the check shows anomalies, those are reported to the ECI. I cannot say that we found any at the entire state level in the exercise concluded in January 2025.”

He shared the standard reports generated on the health of the electoral roll after January 2025. We reviewed these in comparison with the reports generated on previous years’ rolls. At the aggregated state level, the January 2025 electoral roll report showed ratios in the same range as the final electoral rolls of 2024, 2023, 2022 and 2021. This suggests that the update this year had not thrown up any anomalous trend.

“The just-concluded special summary revision did not throw up anomalies at the scale across the state to report to the ECI,” the official added.

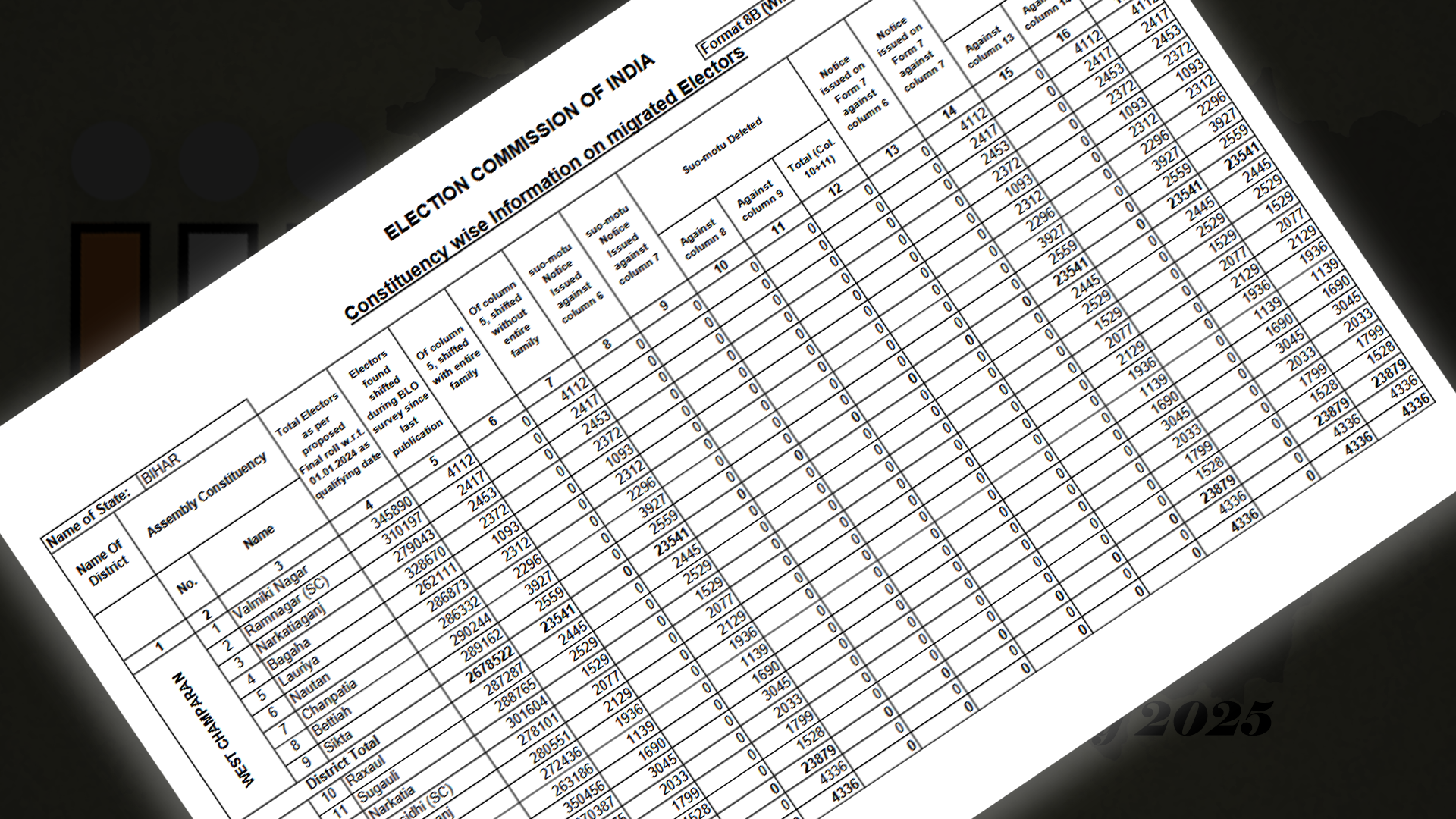

One section of these reports also brings out the constituency-wise information on migrated electors. We reviewed the report. The January 2025 revision report shows that 1,91,222 voters were recognised in the process as having shifted their locations. Unlike the ECI’s claim, going by the records, the Bihar electoral revision process has been steadily capturing migration as well each year.

ECI has not offered any data or proof to back up its claims of big holes in the electoral rolls that it was relying upon till days before its order. Neither have the state officials claimed to identify such holes in the special summary revision of the roll of January 2025.

“The 2003 special intensive revision in several states was undertaken because of the computerisation of records. It treated all citizens as equals and gave everyone adequate time to share their records to claim their right to vote. Without providing hard evidence to either political parties and citizens, this time ECI has ordered different methods for different citizens to prove their identities at extremely short notice,” the retired ECI official said.

There are other fears that the ECI’s hasty orders have unleashed. That of creating doubts about the citizenship of people who get left out of the rolls in this sprinted exercise.

Doubtful Citizens

The law says only citizens can vote. But official records that ascertain the citizenship of an individual remain an unsolvable maze. Therefore, in practice, the Election Commission has avoided becoming the final arbiter of who is and who is not a citizen. It accepted a vast variety of documents as proof of identity to provide the voter cards.

This time, it has expressly mentioned in its orders that the citizenship of voters should be verified. The emphasis has had a rippling effect on the ground in Bihar.

The Reporters’ Collective viewed a video of district officials in Araria district of Bihar, specifically informing the people that the purpose of the exercise was to confirm the citizenship of all those voters who do not figure in the decades-old 2003 voter roll.

“We have previous experience from Assam of such an exercise where voters were put on a ‘doubtful’ list and not allowed to vote. After nearly two decades, we still don't know what happened to them and their rights. No one followed up. I am wary of such a hasty exercise which could end up creating a list of doubtful citizens across the country,” the retired ECI official said.

“Then ECI’s muddled instructions on what documents citizens can provide as evidence of their voting rights will make it terribly confusing and difficult for people. They should have had one exhaustive explicit list,” he added.

How To Prove That You Are

The retired official was referring to the ECI orders, which say citizens have to provide one of 11 documents listed in their order to prove their right to vote. Aadhar and Ration cards have been kept out of the list. There have been fears that the number of fake Aadhaar cards is increasing the inability of the government machinery to validate them biometrically.

After specifying the documents, the ECI order says it's not an exhaustive list. This has led to confusion.

“For officials in the field, you cannot leave it open-ended. These are just badly worded orders. The ECI should have provided an exhaustive list of what all documents are allowed to be submitted,” one Bihar official we spoke to said.

The exclusion of Aadhaar from the list of 11 permissible documents for enumeration validation has not gone unnoticed. While the ECI has attempted to circumvent this issue by headlining its document list as 'indicative (not exhaustive),' Bihar's official information channels are, contradictorily, communicating these as the sole acceptable documents.

The Bihar government’s official regional news unit account on Twitter listed the 11 documents as ones that must be submitted in a graphic tweet to raise awareness on the Special Intensive Revision. The operative word “not exhaustive” was missing.

The marching orders to booth-level officers (BLOs) tasked with conducting this revision exercise were more specific. 'During our training, we were instructed not to use Aadhaar or ration cards as proof of birth or residence,' explained Ganesh Lal Rajak, a BLO from Araria district.

The 2023 Manual of Electoral Rolls, published by the ECI, lists Aadhaar as a permissible document to establish proof of age and residence. In case of non availability of documents, an oath or affirmation from one of the parents, or Sarpanch and even a visible examination by the booth level officer can work as proof of age. The Electoral Registration Officer can do local enquiries to establish proof of residence in the absence of documentary evidence.

The Last Mile Chaos

But now the exercise is going on in Bihar, as we report. We spoke to several booth-level officers, who are to distribute forms for the voters list across the country, and get them filled with evidence.

Facing the ire of citizens, one week into the 30-day exercise, the instructions to the booth-level officers have changed. They have now been told not to demand documentary proof while accepting enumeration forms.

According to several booth-level officers that The Collective spoke with, training days for booth-level officers only started five days after ECI announced the special intensive revision on June 30. By the first week of July, they had been provided the enumeration forms to be delivered door to door.

“Even though from June 25th it was in the papers(news on special intensive revision), the government delayed the training by five days. After that, they delayed another five days to give us the enumeration form," booth level officer Bharat Bhushan from Sitamarhi district told The Collective. Bharat received enumeration forms on July 5th, which he has to distribute and collect within the next three weeks from over 900 individuals for inclusion in the new electoral roll. Bharat also said that he was finding it difficult to upload the enumeration forms online, considerably stalling the process.

One week into the exercise, orders to the booth-level officers have changed as well. Several officers told The Collective that they are now only collecting filled-up enumeration forms with updated photographs, without attaching any of the necessary documentation. This is per oral instructions from the authorities to get the enumeration forms filled at least.

“I was having trouble uploading identity documents along with the enumeration form online, so I was instructed to just get the enumeration form filled and uploaded without the attached documents.” Rina Kumari of Araria district told The Collective.

On July 6, the office of the Bihar Chief Electoral Officer published an advertisement stating more lax rules for the revision exercise, “As soon as you receive the enumeration form … fill it immediately… If required documents and photos are not available, just fill out the enumeration form and give it to the BLO.”

The Collective was not able to establish whether enumeration forms without the requisite documentation for identity will be included in the draft electoral roll. Booth-level officers on the ground have received unclear instructions on how such cases will be dealt with by Bihar’s election authorities.

Krishna Kumar Mandal, a booth-level officer from the Supaul District, said that they have been instructed to set these partially filled enumeration forms without attached documents for identification aside for further assessment by authorities. “If we come across any individual who is unable to produce any of the 11 documents, we have been instructed to get their enumeration form filled anyway, to not scare them and cause public outcry. But we are to set aside these enumeration forms and not upload them online. These will be assessed later to establish how they are dealt with.”

The validation of all 7 crore plus voters of Bihar ordered summarily by the ECI is ongoing. On the evening of July 6, a Union government press release said 21.46 per cent of the enumeration forms had been submitted. The release said, “There are still 19 days to go for the last date for submission of forms.”

“The Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Bihar is being implemented smoothly at the ground level with the active cooperation of the electors,” the government noted. Officials on the ground have been additionally tasked to make some videos of citizens submitting the forms and put them on social media to validate such a claim, we found.

.avif)