Palampur, Himachal Pradesh: During the April-June period this year, just before the monsoon hit Baghjan in Assam, Niranta Gohain, a travel operator and environmental activist from Notun Rangagora Gaon, two kilometres from Baghjan, observed 4-5 teams of researchers surveying the area. His friend Manoj Hazarika noticed the cameras set by them. Hazarika is the village head of Baghjan. On asking, they found out it was for tracking the movement of animals.

Trying to find out more, they approached the Divisional Forest Officer, who informed them it was for a government project. “We have been asked to cooperate to complete the project because it is sarkari kaam (government work). We don’t know much else, except that the project will resume in October,” he told Gohain.

In early July, when Gohain and Hazarika figured that it was to extract oil from under the Dibru Saikhowa National Park using Extended Reach Drilling (ERD) Technology, they were astonished. Last, they knew the forest clearance to use the ERD to extract oil from the park was denied.

But, in January this year, the expert forest panel of the Indian government’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) recommended a research and development project proposed by the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons (DGH) to study the impact of ERD technology on wildlife in Baghjan. The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) is going to conduct the study.

The Reporters’ Collective reviewed the documents available online and obtained through the Right to Information (RTI) Application and found that not only has the ministry’s panel taken a U-turn on its past decision, but the ministry has also let the project operate with existing environmental and wildlife clearances, which may not be valid anymore, say experts.

These clearances are mandatory for any project to go through. One of these (Environmental Clearance) renders the only chance to people living in proximity to a proposed site to weigh-in on the project through a public hearing, and another (Wildlife Clearance) to ensure that protected areas of the country remain so.

In fact, public opinion on extended reach drilling in Dibru Saikhowa National Park has been such a thorn in the flesh of the project proponent, Oil India Limited (OIL), that it obtained even the existing environmental clearance with a special concession from the ministry to bypass public hearing. In effect, no public hearing has taken place in the region since 2016, depriving Gohain and Hazarika and several others from voicing their concerns while experiencing the hardships and risks of living next to an oil drilling site.

This is not all. Special meetings were held, innovative solutions adopted, safeguards customised to the drilling industry’s liking, and the ministry’s own procedures were ignored to let this project through. And it doesn’t seem to be a one-off incident. It has opened floodgates. Even before the WII can come up with its recommendations for mitigating the impacts of the technology on wildlife, a project is seeking approval similar to the one this project received and other two may follow suit once their explorations in protected areas reveal oil.

In India, the MoEFCC primarily deals with three kinds of clearances. Environment clearance, required under the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification of 2006, pertains to the project’s impact on the environment and local people. Forest clearance is required when a project is planned in a forest area, and wildlife clearance is required if the project is located within or near protected wildlife areas, such as national parks or wildlife sanctuaries.

These clearances come through a series of steps, meetings of expert panels and consultations at the union and state government levels, who can reject or approve these clearances. They are aimed at protecting and safeguarding the interests of the environment, the public, forests, and wildlife. Though the process to give these clearances is clearly marked, a lot of times, projects are cleared with exceptions. What has happened is that exceptions happen far too often.

{{cta-block}}

Baghjan- A Site of Deep Trauma and Protest

Today’s Assam doesn’t have a linear relationship with oil and gas extraction. Hydrocarbons brought pride and joy and an opportunity for its people to ‘progress’. They took over the landscape- while oils and gas wells dotted the mosaic of grasslands, marshes, and forests; gas stations shared boundaries with people’s homes and kitchen gardens; pipelines ran through paddy fields; and oil townships segregated and protected the technical from the social. The hydrocarbon operations and communities existed in parallel, but with the former avoiding interaction with the latter.

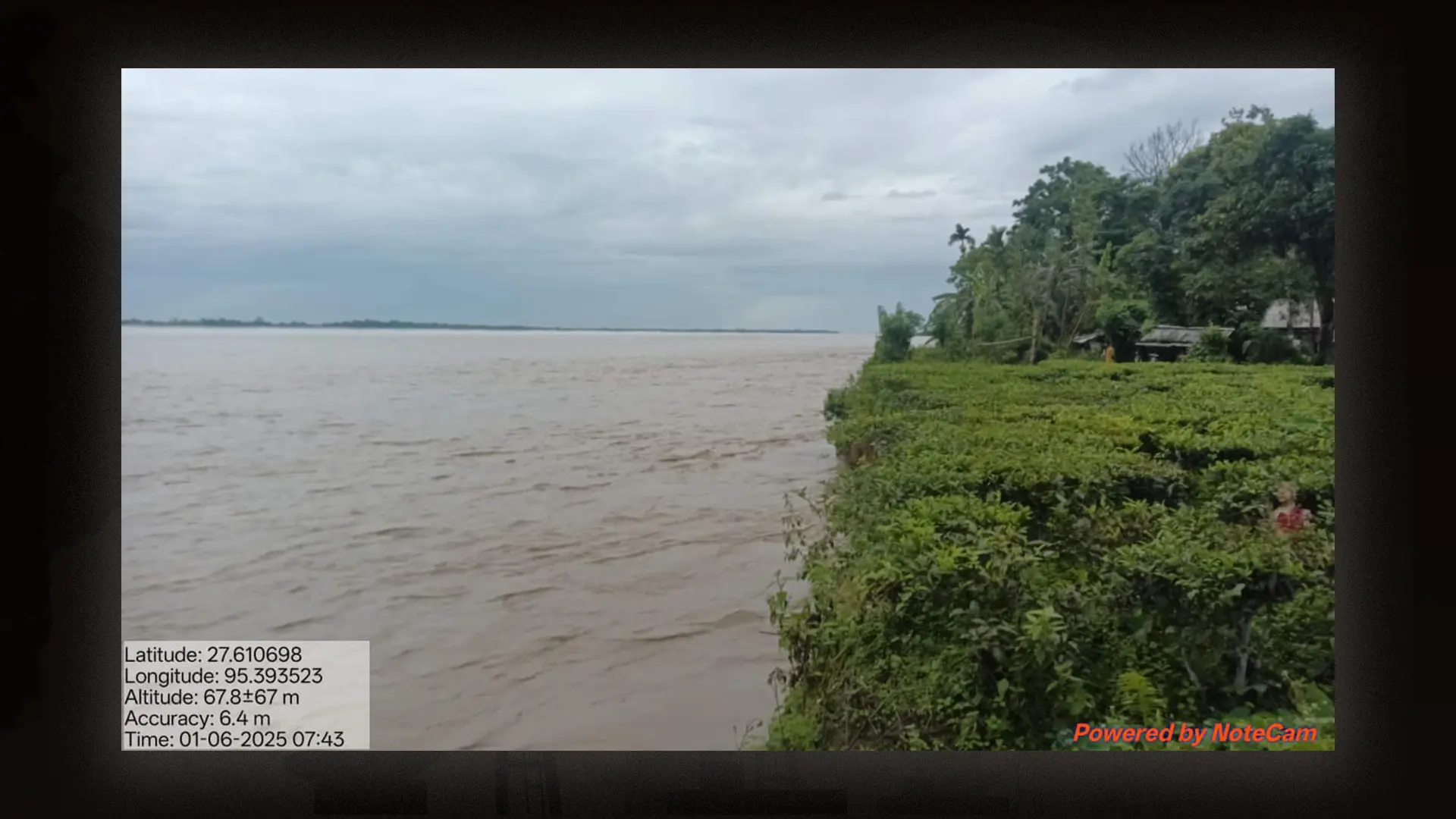

Baghjan oilfield is sandwiched between the Mogari Mopatung Beel wetland and the Dibru Saikhowa National Park. Since 2003, when OIL came to Baghjan, it has operated 22 oil and gas wells in the area. From time to time, inhabitants of Baghjan and nearby villages have held mass demonstrations and road blockades, resulting in the imprisonment of many, who are labelled as “unruly” actors.

Something similar happened in 2016, when, while seeking environmental clearance for operating ERD wells to extract oil from underneath Dibru Saikhowa National Park, Oil India Limited (OIL) claimed before the expert panel for environmental appraisal that conducting public hearings in the area was challenging because of “unruly acts by the local pressure groups”. The panel too accepted the claim and noted that it was “practically impossible” to conduct a public hearing in the area due to “multiple political groups/ NGOs” with “vested interests”.

Apart from feigning ignorance about locals’ grievances, oil companies filled in for the state and met public demands for employment and infrastructure, which facilitated oil extraction and cultivated a sympathising middle class. Effectively, all actions taken by oil companies were directed either to enhance extraction or evade outrage. In absence of a middle ground, only points of encounters between the extractive and community worlds were military watchtowers and checkpoints, points out anthropologist, Dolly Kikon, in her book ‘Living with Oil & Coal Resource Politics & Militarization in Northeast India’.

In June 2020, Well No. 5 of the Baghjan oilfields caught fire, and led to mass destruction to the biodiverse areas. Since the blowout, there has been tension, says Hazarika. The constant fear of another disaster has led to a disconnect between people and their lands. However, he hasn’t lost faith in the possibilities that a public hearing can create. He still demands one- an encounter where a dialogue is possible. “What if a blowout takes place again? We don’t have the information. We need to know what the risks are, and what the preparedness is. Conduct a public hearing, and ask people about their views, allay their fears.”, he says.

How Important Procedures were Given a Slip

The Supreme Court of India has barred certain activities, including mining within a protected area, the notified ecologically sensitive zone that surrounds it, or a one-km-wide buffer if the zone is not notified. In 2016, Oil India Limited (OIL) argued before the Supreme Court that petroleum extraction should not be equated with mining and hence the ban on mining in protected areas should not apply to its proposal to drill oil from underneath Dibru Saikhowa National Park.

The Supreme Court forwarded the case to the Standing Committee of the National Board for Wildlife, which recommended Wildlife Clearance to OIL in July 2017 to ‘extract’ hydrocarbons from underneath the national park. The Court too gave its nod in September 2017.

In January 2020, the Expert Appraisal Committee of the Indian environment ministry recommended the grant of environmental clearance to ‘onshore oil & gas exploratory drilling and testing of hydrocarbons (7 wells)’ from underneath Dibru Saikhowa National Park without it having conducted a public hearing. It accepted OIL’s claims that “multiple political groups/ NGOs in Khagorijan Bagjan area with vested interest, do not allow to conduct public hearing”.

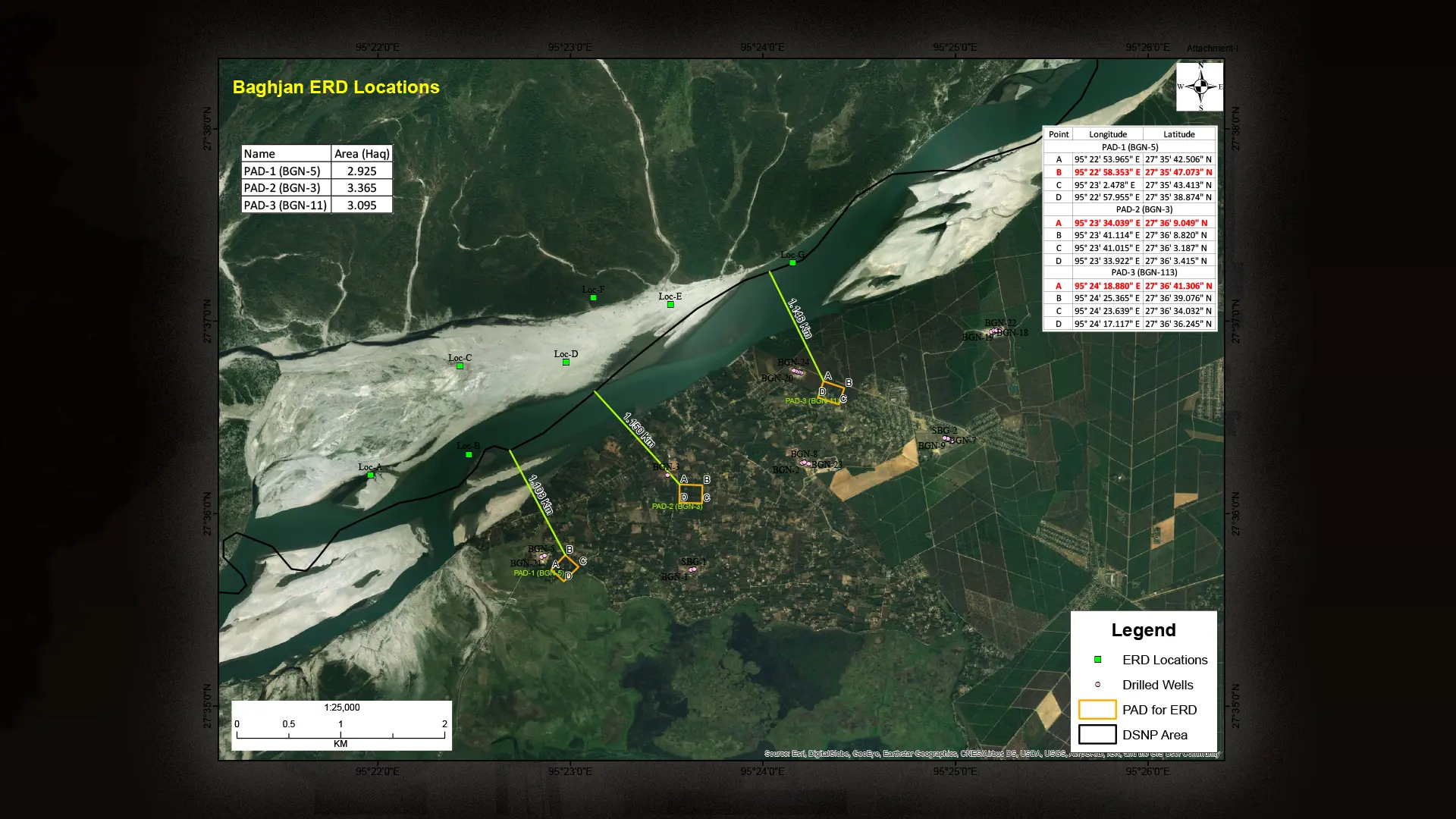

Both these clearances were granted for commercial drilling, albeit environmental clearance for drilling and testing, and wildlife clearance for extraction. Both these clearances were for drilling at seven locations. Both these clearances were granted to Oil India Limited.

The next hurdle before OIL was the forest clearance. OIL would not have to obtain a forest clearance if its drilling sites were not in a protected area. As subsequently in 2023, the MoEFCC lifted the need for forest clearance for the use of the ERD in forest areas, but it didn’t extend this free pass to national parks and sanctuaries.

It meant OIL still had to approach the expert forest panel, and it did. But, in July 2024, the panel rejected OIL’s request to drill seven exploratory bore holes in 0.069 ha of forest land to get oil from underneath Dibru Saikhowa National Park using Extended Reach Drilling.

Now was the Time to Shift Gears!

In November 2024, the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons organised a meeting with OIL, WII, and the MoEFCC to overcome the ‘impasse’ and came up with an ingenuous solution- to apply as a research project!

And the research proposal did get through. In January this year, the expert forest panel recommended the proposal for forest clearance.

So, what changed between July 2024 and January 2025?

This time, the clearance was sought to conduct ‘research and development drilling activity’ to assess the impact of ERD without commercial implications. This time, the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons proposed the project. This time, the proposal came directly to the Central panel, unlike the usual course where the project proponent submits the proposal to the State Government, which then forwards it to the Centre.

“How can a clearance obtained for commercial use be used for research? These are two completely different purposes.”, asks Prakriti Srivastava, a retired forest service officer.

The environmental clearance that the project received in 2020 restricts any modification other than what is allowed in the Indian environmental impact assessment law without prior environmental approval. If any ‘deviations’ are made to the project, the clearance requires that a fresh proposal be made so that the adequacy of the imposed environmental protection measures can be assessed.

This raises the question - if all this was changed, why did DGH not change the sites of drilling too - keep them outside the protected area, avail the free pass and carry out its research?

No Forest Diversion, so No Need for Forest Clearance

In May 2019, the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas constituted the Empowered Coordination Committee. It takes up the matters of delay/non-issuance of various clearances to oil & gas operations with concerned ministries/departments for their quick ‘resolution’. The committee decided to discuss the need for forest clearance for the extraction of oil and gas from forest areas by drilling from outside using directional technology.

Following that discussion, the MoEFCC created a committee with the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education (ICFRE) and petroleum industry experts to study the impacts of ERD technology on above ground biodiversity. In its recommendations, the committee inferred that there were no direct impacts of the technology. But due to the risks associated with leakage and spills, it recommended a minimum linear distance of 1 km from the boundary of protected areas and wildlife corridors and 0.5 km from other forest areas.

Using this study, the DGH proposed before the expert forest panel in February 2022 that since no activity is being undertaken in the forest area, and no real diversion is taking place, the use of ERD should be outside the purview of the Forest Conservation Act. The expert forest panel agreed in-principle but asked for the opinion of the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) on the likely impact of wildlife.

WII carried out a rapid assessment of the existing ERD sites and, in May 2023, suggested a draft Standard Operating Procedure for use of ERD technology in forest areas without forest approval. Among other safeguards, it suggested that drilling should be discontinued during peak wildlife movement hours.

The DGH, however, wanted the drilling to go according to the drilling schedule. WII relented.

In August 2023, the MoEFCC passed the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act and subsequent guidelines that kept ERD outside its purview. In September 2023, the ministry accepted the Standard Operating Procedure suggested by the WII. The final Standard Operating Procedure didn’t suggest discontinuance of drilling during peak wildlife movement periods.

The environment ministry also asked WII to come up with site-specific safeguards to mitigate impacts on wildlife.

ERD or Tedha Wells

Horizontal Directional Drilling (HDD) and Extended Reach Drilling (ERD) both allow vertically-drilled paths to deviate horizontally, much like a straw we use to drink out of a glass. J-well or Tedha well, as it is referred to locally, is an ERD well that involves an advanced form of directional drilling, in which the horizontal reach is much longer than the vertical depth, clarified an expert in drilling technology from Dibrugarh, Assam. He wished to remain anonymous.

In India, ERD and HDD wells have been drilled in several locations, including Barmer of Rajasthan, Rajahmundri region in East Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh, and Sibasagar and Tinsukia districts of Assam.

“Tedha wells toh yahan kafi samay se drill ho raha hai. Par Dibru Saikhowa mein bhi yahi kar rahe hain nahi maloom (Tedha wells have been around here for quite some time. But we don’t know if they are drilling those in Dibru Saikhowa as well).”, said Gohain.

A September 2024 paper on the environmental impact of horizontal drilling by researchers from Taipei University states that while the technology cuts down the number of drilling sites needed, it still requires infrastructure such as roads, well pads, and pipelines, “which can disrupt local ecosystems”. The paper also highlights the risks of spills and leaks, which can contaminate the groundwater and the aquifers. It, in fact, suggests that drilling in critical habitats should be avoided as it can lead to habitat fragmentation, disruption in migration patterns, and wildlife population decline.

The committee constituted by the MoEFCC too identified indirect impacts of the use of ERD- forest fire resulting from oil leakages, pollution from organic compounds found in crude oil & gas that can lead to reproductive effects and risk of soil surface contamination.

WII, in its report on rapid assessment of the ERD drilling sites that The Reporters’ Collective obtained through an RTI application, albeit meekly, recognises that noise from the construction of such infrastructure and drilling itself can impact animal behaviour.

.webp)

Is it a mere coincidence that OIL drilling sites are just over a km away from the boundary of Dibru Saikhowa National Park, and the MoEFCC committee suggested a minimum distance of 1 km from the boundary of a protected area for the use of ERD?

When asked about what should be the minimum distance between the drilling hole and a sensitive area, the expert from Dibrugarh replied, “the distance (between the hole and the sensitive area) depends on the drilling design. Several aspects need to be looked into. But as a principle, it should be multiple kilometres away from a sensitive area to avoid damage in case of an eventuality such as leaks.”

The expert also highlighted that regular operation and maintenance works, especially for old wells and maintenance of a safe distance from forest areas or ecologically sensitive areas, can substantially reduce the risks of any damage. When asked about OIL’s track record on maintenance, the expert chose not to comment. But the Baghjan blowout was not the last incident that took place in OIL’s fields. Since then, four more incidents have taken place.

- Fire at Numaligarh Refinery in May 2023

- Gas leakage and pipeline blast in Duliajan during repair in February 2024

- Leakage in X-mass tree assembly above the crude oil well at Dighaltarang Tea Estate in Tinuskia in April 2024

- Major gas leakage in Duliajan in May 2025

Even the overall data of incidents at hydrocarbon operations is not too promising. 16 incidents of gas leakage and fire breakouts were reported to the Oil Industry Safety Directorate in 2018-19, 10 in 2019-20, and 5 in 2020-21, as shared in the Loksabha in 2021. According to the Safety Directorate’s annual reports, 22 incidents were reported in 2023-24, and 13 in the first six months of 2024-25.

Is it a Slippery Slope?

Coming back to the question of why the DGH did not choose a site outside a protected area to study the impact of ERD on wildlife, Srivastava senses a bigger plan. “Involving WII seems like a fig leaf that the ministry is trying to give itself before it signs off on the permission to extract oil and gas from protected areas in general,” she says.

We asked MoEFCC, WII, and the DGH, why a protected area and not a less sensitive site was chosen for this project. We also asked OIL about the safeguards it has put in place to avoid risks. We will update the story if and when we receive any replies.

Many scientists have highlighted in the past how WII has been used as a convenient cover to greenlight controversial projects. Several assessments and studies carried out by WII have been alleged to be underplaying the negative impacts of mega projects, being rushed, or marred with a conflict of interest. Even the rapid assessment report that WII based its recommendation for exemption of forest clearance for use of ERD on, starts with the acknowledgment that hydrocarbons are critical for India’s energy security. And why not, after all, the study was funded by the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons, whose mandate is to promote sound management of oil and gas resources of the country!

“Why go to a protected area to carry out this study? Wildlife is found even outside national parks and sanctuaries. In fact, it could have been an easy way out. No forest clearance needed. Why take the tough route? There must be some bigger incentive.”, suspects Srivastava.

Bigger things are definitely at stake. New discoveries have been made in the North East, especially in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. Hardeep Singh Puri, the Indian minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas, has pitched ecologically important marine areas of the Andamans as India’s Guyana moment. The opening of the protected areas for hydrocarbon extraction will come in handy. As for the Supreme Court restriction, in March this year, the Oilfields Amendment Act 2025 was passed. It differentiates petroleum extraction from mining, creating an escape route for future proposals located in protected areas and ecologically sensitive areas from the application of the Supreme Court ruling.

In fact, recently, Dibru-like forest approval is sought for the use of ERD in Dehing Patkai Wildlife Sanctuary, suggesting that perhaps, the panel’s nod to this R&D project has opened the floodgates for oil extraction from protected areas. In January, the Standing committee for wildlife allowed exploration drilling in the ESZ of Hollongapar Gibbon Wildlife Sanctuary in Assam on the condition that no oil will be extracted from inside the ESZ. ONGC too has sought to carry out exploratory drilling in the protected areas of Golaghat in Assam.

For now, wells 3 and 11, from which the four points for extended reach drilling will be accessed, are operational. ERD technology may as well be in use there. But locals continue to be in the dark. “Well 3 aur 11 se production toh chalu hai. Ab zameen ke andar kya karte hain aur Dibru Saikhowa tak gaye hain ki nahi, humein kya pata chalega (Production is ongoing from wells 3 and 11. We have no way to find out what they are doing subsurface and if they have reached Dibru Saikhowa or not).”, shared Hazarika.