New Delhi: The ECI has claimed before the Supreme Court that it found its deduplication software to be so bad that it stopped using it after 2023 and consequently did not use it for the countrywide Special Intensive Revision, which began in Bihar in June 2025.

ECI’s rubbishing of its own software before the Supreme Court stands in stark contrast to the vote of confidence the commission gave to its software in 2023, when it ordered officials across the country to deploy the software in ‘campaign’ mode across 100% of the voter roll to identify suspect duplicates ahead of the 2024 Parliamentary elections.

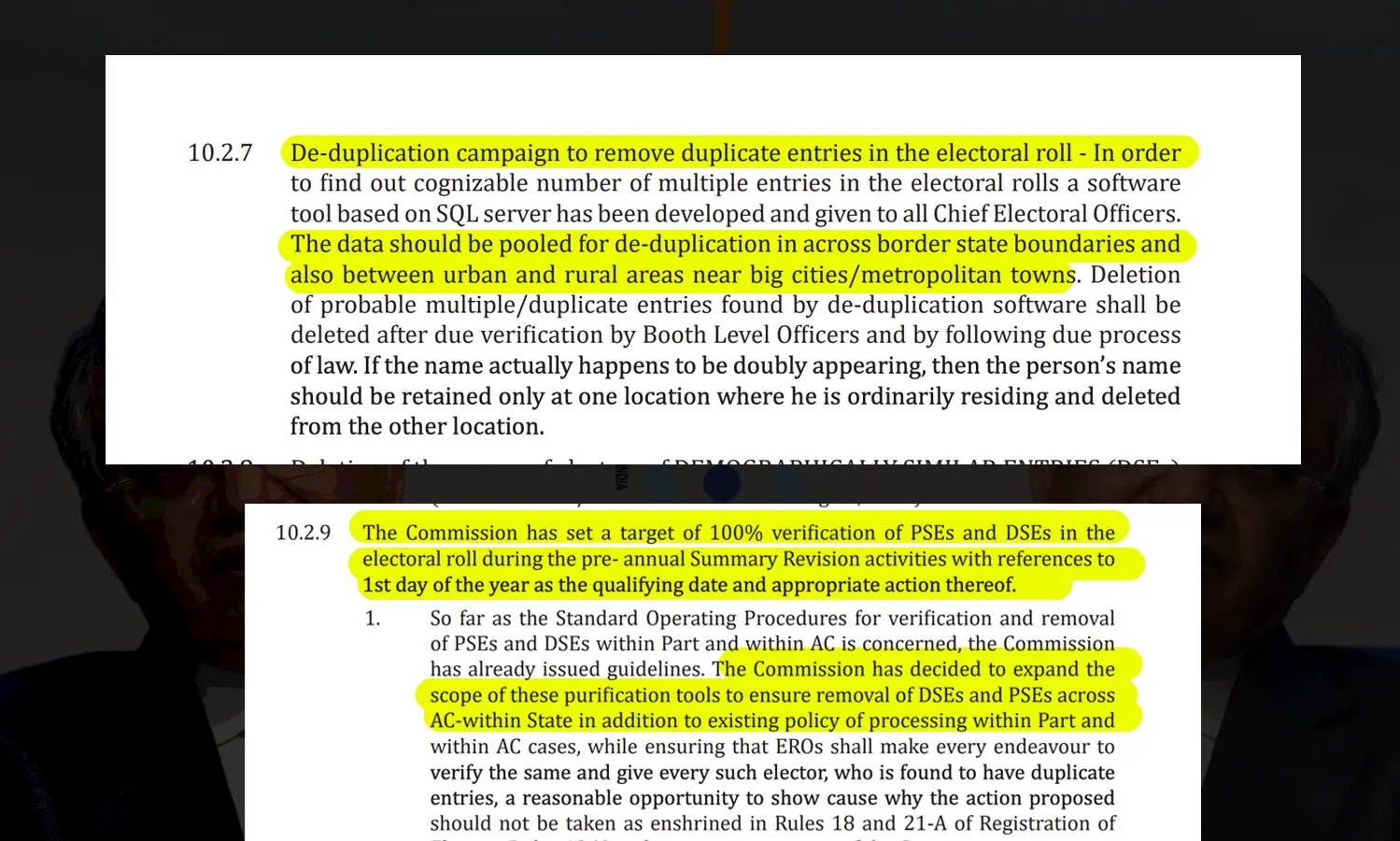

These orders form part of the ECI’s Manual on Electoral Rolls that was published in March 2023. ECI’s manual is binding on election officials, and the 2023 version remains in force, at least on paper, to date.

But on November 24, 2025, ECI filed a counter-affidavit before the Supreme Court, asserting that the deduplication software was so defective that it warranted a complete discard.

ECI told the court, “The strength and accuracy of the results were variable and large numbers of suspected DSE (demographically similar) entries were not found to be duplicates. The said technology was last used in 2023.”

The commission made these claims in response to a previous investigation by The Reporters’ Collective, which, for the first time, revealed that the deduplication software was not used in the Bihar SIR. The investigation had been cited in the court proceedings, forcing ECI to give a response. It's first in the public domain about the disuse of the software.

No evidence was provided by the commission to back its claims of the software being defective.

ECI also claimed before the court that its method in Bihar SIR - to leave it to citizens not to register twice - was more reliable than its computer-based detection, which it termed as a “random search by software”.

But, another one of our previous investigation had shown that 14.35 lakh suspect voters with two or more voter IDs remain on the finalised Bihar list, which the ECI had claimed to be ‘purified’. Elections for the Bihar Legislative Assembly took place on November 6 and 11.

{{cta-block}}

The Software

In 2018, ECI deployed a new software which used machine learning methods to identify duplicates. This software was in the hands of state election officials as well, incorporated into ECI’s IT interface for Electoral Officers, called ERONET.

The Election Commission’s presentations on ERONET reveal that this application could identify suspect entries that are demographically similar. In other words, it detects similarities in names, names of relatives, addresses, and ages to identify suspect duplicates and fraud. It can also match photographs on Voter IDs (called EPIC) to detect potential fraud and duplicates.

In the interim years, the deduplication software has been used several times during the annual revision process of voter lists.

But by the time SIR was announced, ECI had quietly discontinued its use.

While the SIR exercise was deemed to “completely purify” voter rolls by the Election Commission. Bihar’s local election officials told The Collective at the time that they were relying on voters to self-report or booth-level officers to manually catch instances of duplication. The result is countless cases of duplicates who continue to exist on Bihar’s voter list. The same voter list which voted in the recently concluded assembly elections in the state.

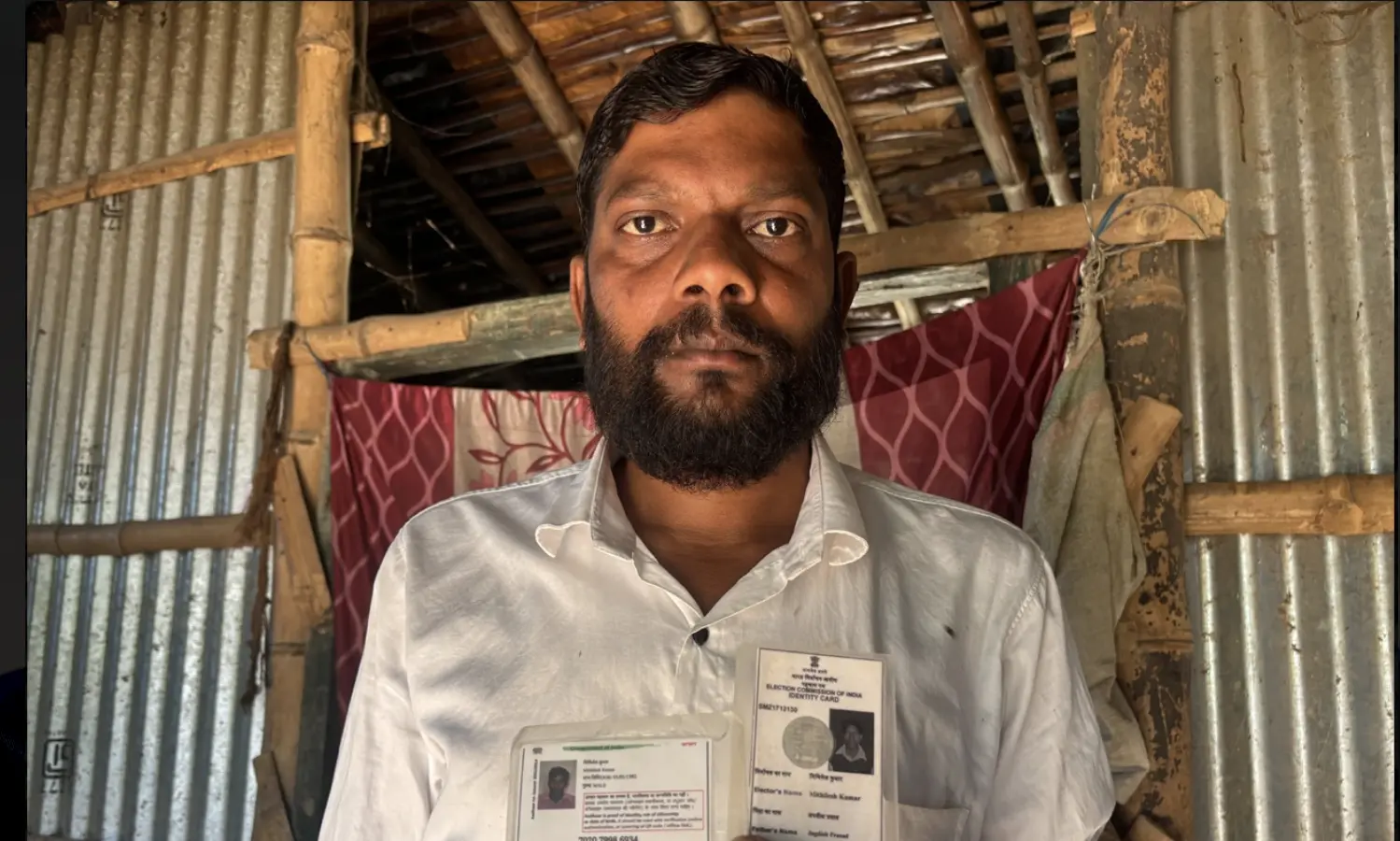

Take the case of Mithilesh Kumar in Jale assembly constituency. We found that Mithilesh had two duplicate voter IDs. The Reporters’ Collective reported this case while the verification was ongoing. Yet Mithilesh’s two IDs continue to exist on the finalised voter list. We confirmed.

ECI told the court that voters would need to declare that they hold only one voter ID while filling out the enumeration form for SIR. In the case of a false declaration, the individual would be held liable under the Representation of the People Act.

But here is why Bihar SIR’s manual process does not work.

ECI’s process assumes that voters will be honest when filling out enumeration forms, even if they weren’t honest earlier. However, those who purposefully create duplicate voter IDs have no reason to be truthful. Without an algorithmic check, ECI has no way to verify the voter’s declaration.

The ECI relies on the booth-level officials or the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) to check for any duplication manually. But they have access to electoral rolls either at the booth level or, at best, at the constituency level. They cannot verify these against crores of voters in other parts of a state to detect those who have registered in two or more constituencies.

In the case of migrant workers, the search for duplicates needs to be carried out across state voter rolls. Only the ECI has access to the entire country’s voter database. Therefore, even state-level officials of ECI cannot manually hunt down duplicates.

It can be done only through computerised methods.

During our checks of Bihar’s voter roll, we found suspect duplicate IDs within booths, across booths, across assembly constituencies, and in the case of migrants, across states.

The suspect cases, as the ECI’s manual noted, had to be verified on the ground by giving notice against multiple voter IDs and then reconciling to see where the person lives, if at all. The other IDs are then to be deleted.

The digital discovery of suspect duplicates can throw up some false cases. But when we ran our own deduplication algorithm in Bihar and followed up with ground checks, we found several cases of verified duplicates.

In some cases, obvious duplications have made it to the final voter list.

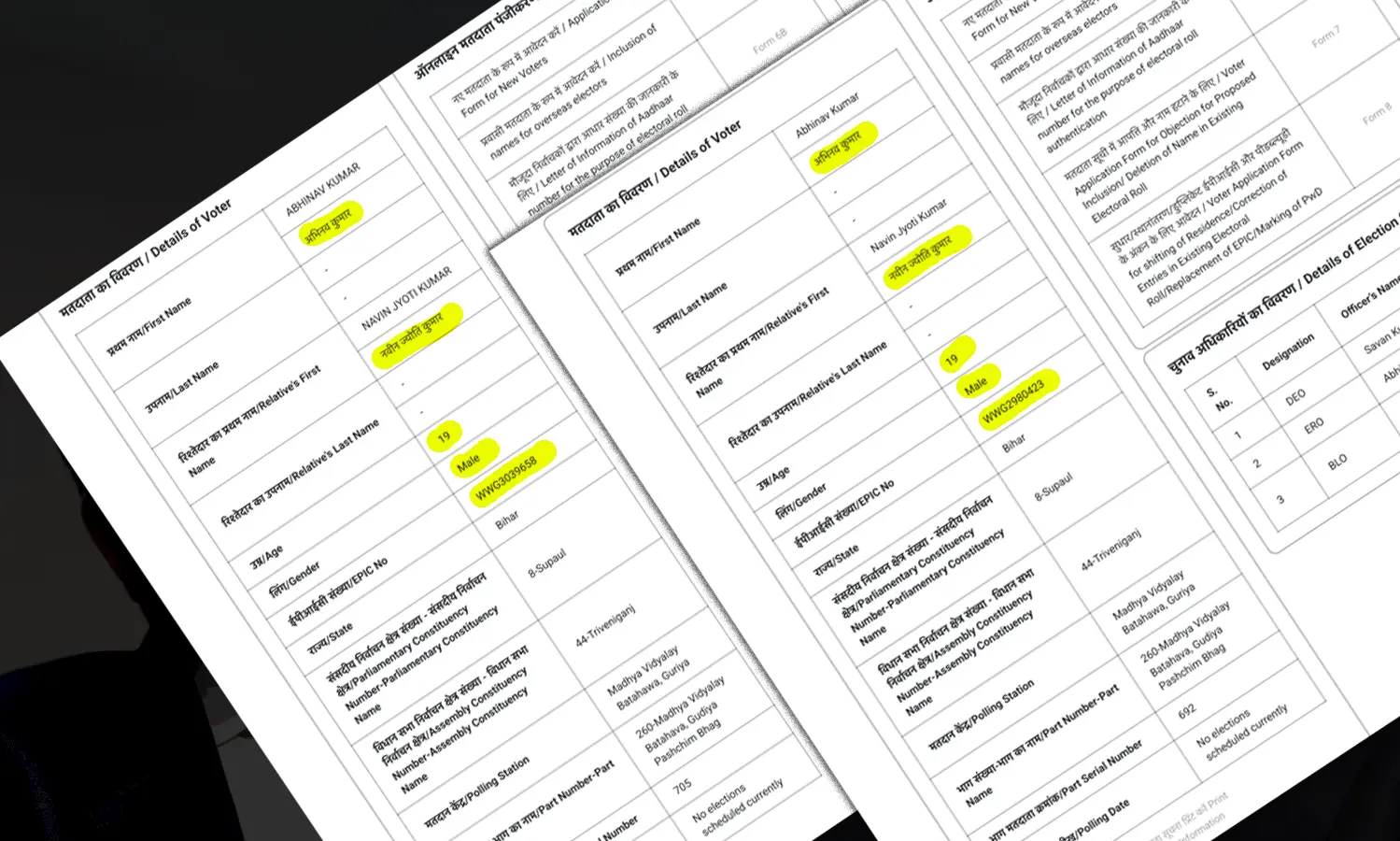

Take the case of Abhinav Kumar from the Triveniganj assembly constituency. 19-year-old Abhinav has two EPICs registered on the same house address. All demographic parameters match perfectly. If the software had been deployed, this entry would have been flagged for additional verification. But ECI relied on Abhinav to truthfully declare that he held only one EPIC.

Only ECI can verify all suspect duplicate entries. It has, on several instances, shared lists of suspected duplicate voters with state election authorities to verify. It did so in Bihar right before the 2024 Lok Sabha elections.

During SIR, it has decided to go with a rushed month-long process and no list of suspect voters at the baseline.

And yet, the chief election commissioner has categorically underlined that no software will be used to flag duplicates in Phase 2 of SIR, being carried out across 12 states. The state election authority of West Bengal recently hinted that it may introduce Artificial Intelligence-based voter verification during the special intensive revision process.

“Sources” close to the West Bengal CEO office have said that the AI-based verification technology would help detect cases where the same photograph has been used to enrol multiple voters.

Recently, during the latest hearing, ECI told the court that they are open to adopting technological tools wherever found most effective, and are working on improving available technologies.

However, no audit or disclosures of these tools are publicly available. Neither is the process that ECI uses to decide when these technological tools will be deployed.

.avif)