Kolkata: The Election Commission of India’s use of an untested, undocumented and regularly-revised software has landed officials in West Bengal in a quagmire to conduct quasi-judicial hearings to determine the citizenship, identity and voting rights of 1.5 crore electors in less than 20 days.

The Reporters’ Collective reviewed official records and internal data of the ECI in West Bengal, oversaw the functioning of its software applications, interviewed five assembly-level election officials, a source in ECI’s state office and more than a dozen booth-level officials to understand how the ECI ended up summoning more than 18% of the state’s voting population to queue up to prove their identities and voting rights afresh.

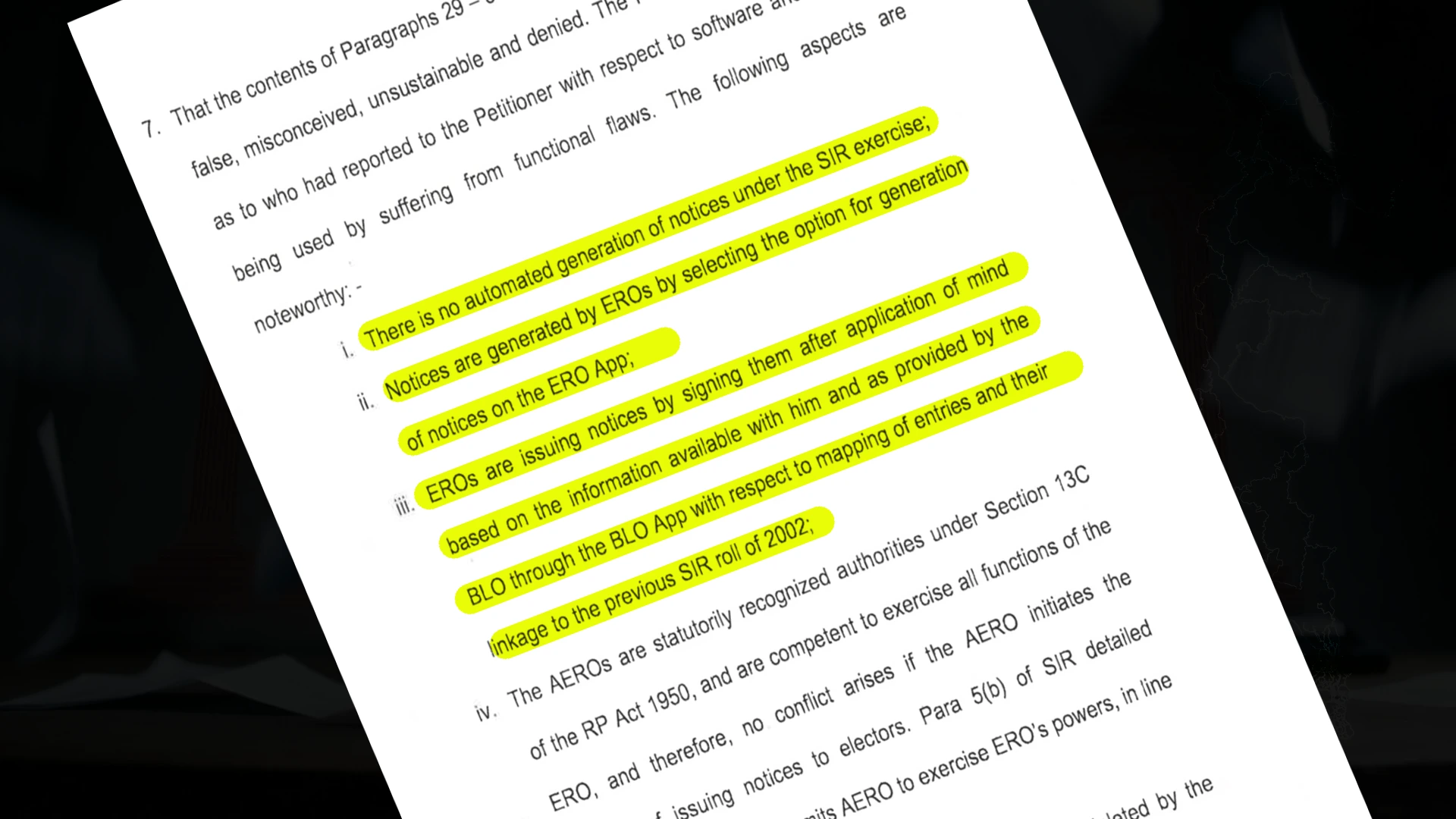

We found that the ECI had misled the Supreme Court. It told the court, “There is no automated generation of notices…. EROs (Electoral Registration Officers) are signing them off after application of mind.”

EROs are the constituency-level officials, who hold the power and the responsibility to prepare, update and revise electoral rolls for an assembly constituency. The ECI sets the process and method by which the rolls are updated. The EROs, and not the ECI, are alone empowered to finalise voter lists based on these regulations.

Our investigation shows, contrary to the ECI’s claim before the Supreme Court, the notices in West Bengal have been generated en masse by centralised and untested algorithms for cases the ECI euphemistically termed as ‘logical discrepancies’.

The EROs, forced to review thousands of such cases every day, were each left with no choice but to perfunctorily sign off on tens of thousands of notices to citizens within two weeks when flagged by the Commission’s software as suspicious.

ECI digitised the paper records of the 2002 voter lists. Most of the records were in Bangla. They were translated into English by computers through untested algorithms. The ECI then used other algorithms to compare the digitised version of the 2002 lists with the filings of voters who had claimed that either they or their elders existed on the 2002 list. The software marked more than 1.31 crore voters as suspicious.

West Bengal’s CEO office internally acknowledged that the software protocol rushed midway through the revision exercise was mired with errors, flagging a staggering volume of voters. To correct this, ECI empowered local election officials and booth-level workers to discount minor errors for the first few weeks. However, the Commission continued to introduce new filters and criteria in the software to flag suspect voters and changed course yet again.

On paper, the electoral officers were asked to ‘apply their minds’ to each case before sending people notices. It was an impossible task. Unwilling to take the risk of ‘getting it wrong’ and hard-pressed to meet impossible deadlines, local election officials abandoned discretion. ECI’s constituency-level officials pressed the necessary buttons on the ECI software to print notices in bulk and then sign them off en masse.

A senior official in the Chief Electoral Office of West Bengal told The Reporters’ Collective that the overwhelming number of voters red-flagged with ‘logical discrepancies’, is now preventing them from filtering out voters with minor discrepancies to skip these summons. All voters are being ordered to attend ECI’s quasi-judicial summons for the ongoing Special Intensive Revision, or present a legal representative on their behalf.

“For the most part, we were signing off on 4,000 summons each day,” said an Electoral Registration Officer in Kolkata. Overseeing a constituency with one of the city's highest concentrations of red-flagged voters, the official spoke to this reporter on the condition of anonymity.

As a top official for ECI put it, “With such a large number of notices generated, especially for voters with logical discrepancies. It is a near-impossible exercise for EROs to review and drop minor errors.”

ECI’s internal data, reviewed by The Reporters’ Collective, reveals a massive administrative backlog as of January 24: While over 1.5 crore summons were prepared, officials have delivered only 95.39 lakh, with just 30 lakh voters attending proceedings by January 24.

A month into the exercise, the Commission has completed only 20% of its planned hearings. This leaves just three weeks to process the remaining 80%—nearly 1.2 crore voters—before the final rolls are published on February 14. The number of voters verified so far stands at 7.24%. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s direction to modify the exercise yet again is expected to further increase backlogs.

We sent questions to the ECI to respond to the story. It had not responded by the time of publication. The story will be updated if it does.

Two Discrepancies, One Software

As ECI ushered citizens to take part in the nationwide SIR in 12 states and union territories, it reassured voters that the bureaucratic burdens on voters would be limited. The Commission was preparing an internal mapping software to digitally link the majority of voters to the 2002-2004 rolls of the special intensive revision undertaken two decades ago. Those who pass this digital test will not need to submit any documents for enumeration, they committed.

Months into the exercise, the software deployed without due vetting threw crores into the dragnet of suspicion. In just two states, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal, we found that over 3.66 crore voters had been considered suspicious by this new protocol.

What has ensued, at least in West Bengal, is a tangle of contradictory protocols putting election officials into a tailspin as they try to handle the overwhelming notices issued, all in the hope of adhering to the previously committed three-month deadline for the revision.

While similar procedures are being followed in all 12 states that are currently undergoing the revision, with our limited resources, we focused on one state, West Bengal. We interviewed officials at the CEO’s office, election officers, booth level workers. We accessed notices and letters issued in the interim, changing protocols, and we created the timeline.

Here it is, ECI’s Algorithm-Generated Chaos

When initially deployed, ECI’s software was marking voters as unmapped, even while on paper voter rolls, they or their ancestors appeared on the 2002 voter lists. According to West Bengal’s draft voter lists published on December 16, over 32 lakh voters in West Bengal were unmapped. This meant that, according to the ECI, neither they nor their ancestors appeared on the 2002 voter lists.

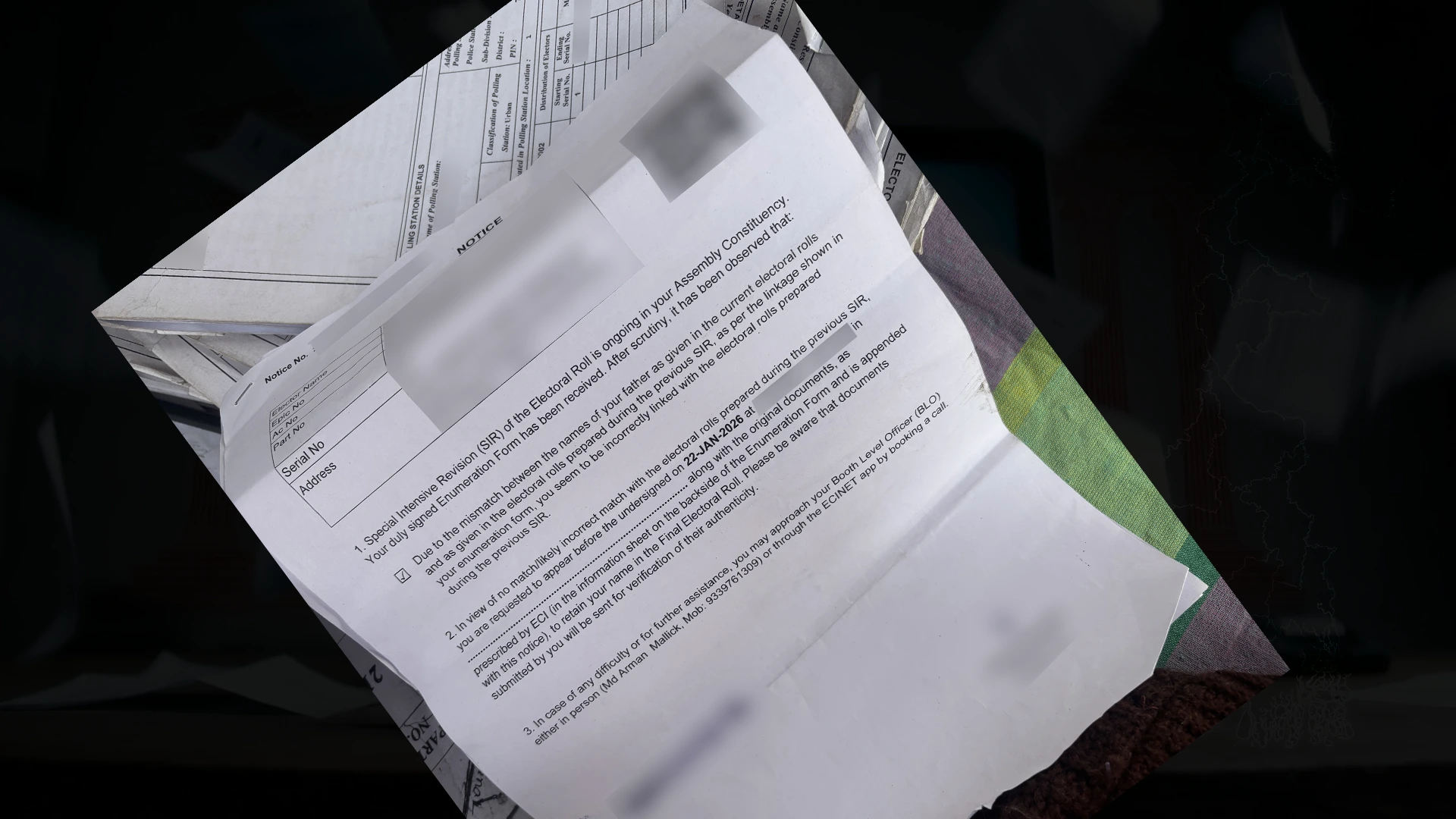

Starting December 27, these ‘unmapped’ voters were served notices summoning them to quasi-judicial hearings, where they were required to produce one of 13 specified documents to prove their citizenship. Yet, just forty-eight hours after the first summons went out, the software was flagged as fundamentally flawed.

In an internal letter to district election officials on December 29, the CEO West Bengal office acknowledged that there were “sporadic errors in conversion of the 2002 electoral rolls into CSV.”

Consequently, ECI allowed election officials to summon unmapped electors for in-person hearings on a case-by-case basis. If voters appeared on the hard copy of the electoral rolls on manual examination, then “...BLO may call and inform that he (the elector) may not appear,” they clarified. ECI submitted as much to the Supreme Court.

By marking voters as 'unmapped,' the Commission expected to identify dubious voters, including illegal migrants fraudulently added to the state’s voter rolls. However, contrary to these expectations, only 3% of Bengal’s electorate was flagged as unmapped, with numbers proving unexpectedly low even in the frontier constituencies.

ECI decided to expand its scope of inquiry. The same matching software was now deployed to find ‘logical discrepancies’ amongst mapped voters. If there were discrepancies in spelling between the names in the 2002 and 2025 voter rolls, if six or more voters were linked to the same ancestor, or if the difference in ages between the voter and the ancestor mapped did not clear ECI’s criteria, they would be red-flagged as ‘logical discrepancies’.

Another 1.31 crore voters were now in the ECI’s dragnet of suspicion. Data on the notices reveals that their geographic distribution follows predictable lines: Muslim-majority districts such as Malda and Murshidabad, which border Bangladesh, emerge as the state’s hotspots for logical discrepancies. These districts initially had significantly low percentages of unmapped electors.

Similarly, in Nadia, another hotspot for SIR hearings in general, sources in the district reveal that so far the largest number of hearing notices generated for the recently announced logical discrepancies are for Kaliganj, Nakashipara and Palashipara assembly constituencies. All three have significant concentrations of Muslim residents, ranging from 27% to more than 50% of the population.

In the state capital, the assembly constituency of Kolkata Port throws the highest number of logical discrepancies, along with the notices generated. This densely populated assembly constituency has a significant Muslim population, estimated at nearly 50% of the electorate.

Interviews with local election officials and several booth-level officers confirmed that fundamental flaws persist in the ECI’s software for identifying logical discrepancies. Booth-level officers who spoke to this reporter agreed that cases of minor inconsistencies far outweigh those of serious mismatches.

The primary issue, as a senior official explained, is that the software translates voter rolls from Bengali into English before attempting a match. In numerous instances, the traditional English spelling of a surname differs from the software's automated transliteration of the Bengali script.

Take, for example, the surname ‘Xalxo,’ common among the Oraon tribal community near the Jharkhand border. While most community members spell their name as ‘Xalxo’ in English, the software transliterates the Bengali script into the phonetic spelling ‘Khalkho,’ triggering a logical discrepancy.

If, over time, voters have slightly modified how their names are written, 'Mohammed' becomes 'Md', 'Sheikh' becomes 'Sk', 'Chattopadhyay' becomes 'Chatterjee' it too will be flagged.

“These are minor errors that a booth officer could fix in seconds without summoning anyone. They live in these communities; they know exactly who these people are,” a booth-level agent for Trinamool Congress told this reporter. He, along with other party workers, had pitched a makeshift help tent at the threshold of an SIR hearing centre in Khidripur, Kolkata.

A booth-level officer from the same centre said, “If ECI allowed me to review and selectively issue notices, half of the voters summoned in my booth would not have to show up for SIR hearings.” He spoke to The Reporters’ Collective on conditions of anonymity.

Meanwhile, in response to the Trinamool Congress’s petition in the Supreme Court regarding logical discrepancies, the ECI has submitted that EROs are ‘applying mind’ before issuing notices. This submission was a direct rebuttal to the Trinamool’s argument that it is logistically incomprehensible to conduct SIR hearings at such a frequency within a limited timeframe.

It told the Court, “EROs are issuing notices by signing them after application of mind based on information available with him and as provided by BLO through the BLO App with respect to mapping of entries and their linkage to the 2002 rolls.”

Via leaks to the press, senior ECI officials claimed that BLOs have been instructed to resolve minor errors flagged as logical discrepancies internally and not call them for hearings. We confirmed at several levels of seniority that this is not the case.

A booth-level officer told this reporter, “I have given notices to all those with logical discrepancies, it doesn’t matter if the difference is a single syllable. I will not risk it.”

The Conveyor Belt of Suspicion

EROs interviewed by The Reporters’ Collective portrayed a conveyor-belt reality of issuing summons.

We spoke to two EROs, one in Kolkata and one in Nadia, who, along with a few deputies, were signing 4,000 to 5,000 printed hearing notices each day. These printed notices are then manually delivered to voters for hearings.

The ERO from Nadia further said that in his case, he was calling all unmapped voters as well, even while the ECI allowed officers to not issue hearing summons to all unmapped voters.

When we asked a senior ECI official at CEO West Bengal why our interviews with election officials locally contradict ECI’s submissions to the Supreme Court?

He said quite candidly, “For logical discrepancies, it is a near impossible exercise to selectively discard notices, given the sheer volumes of notices generated.”

He went on further, “What they have done is that ERO is opening ERONET (ECI’s application for constituency-level election officials), and seeing that for this part, these number of notices on logical discrepancies have been generated. So he will give the command of printing that part’s notices. At the point of ERONET itself. Now, whether you can practically call it an application of mind, or a partial application of mind, or no application of mind—that is a question of degree, I suppose.”

How does one legally define ‘application of mind’? The vagueness of the term has allowed the ECI to mislead the Supreme Court on how the algorithms, and not the legally-empowered EROs at the constituency level, are driving the SIR and the 1.5 crore people of West Bengal into queues to reaffirm their existence and rights.

.avif)