Pipra, Bihar and Delhi: The Election Commission of India (ECI) has registered 509 voters from different families, castes, and communities as living together in a single house of Galimpur village in Pipra assembly constituency of Bihar. The number alone is not the striking part. In reality, the house does not exist.

In the same village, there is another case, in a non-existent house, the ECI had registered 459 people as voters in the Pipra constituency.

This is not a one-off error in the ECI’s unprecedented exercise to revise the entire country’s voter database from scratch, starting with Bihar, an investigation by The Reporters’ Collective has found.

In Bihar’s three assembly constituencies, Pipra, Bagaha, and Motihari, our investigation unearthed 3,590 cases where ECI has registered 20 or more people at a single address. In many cases, the houses did not exist, we found. Incredulously, over 80,000 voters have been registered in the three constituencies in this manner by the ECI.

Typically, 20-50 individuals were registered under the same address. These addresses ranged from being simple numeric house numbers to names of villages or wards in certain cases.

We found several cases in the three constituencies that were worse. Bagaha's electoral rolls revealed nine households with over 100 voters registered to the same address. One household, the largest, had 248 individuals. Motihari assembly constituency had three cases of 100 or more voters registered at non-existent addresses, the largest being a house where, going by ECI’s new voter list, 294 voters of different families, castes, and communities live together.

Between the Pipra, Motihari, and Bagaha assembly constituencies in the Champaran region of Bihar, there are around ten lakh registered voters. This could mean that approximately eight percent of total voters are registered at dubious addresses.

This is the result of the 30-day sprint ECI carried out as part of its Special Intensive Review (SIR) of Bihar’s electoral rolls, which it claimed would ‘purify’ the state’s voter database before the upcoming assembly elections.

The Reporters’ Collective collaborated with a group of independent data analysts to study ECI’s freshly prepared voter data of just three Bihar assembly constituencies, to begin with, Pipra, Bagaha, and Motihari. We then sent a colleague to verify the results of the data analysis from the constituencies.

Our investigation has thrown up startling proof of systemic and large-scale flaws in the SIR. The data shows, at least, the ECI’s hastily executed exercise has failed to purge the problems, errors and ghosts from the past voter databases. And, worse, it has potentially filled the database with more.

Dubious and Fake Houses Packed with Voters

The issue of voters registered under dubious addresses was brought to the fore once again this month by Congress leader Rahul Gandhi. In the Mahadevpur constituency in Central Bangalore, Gandhi revealed 80 individuals who were registered to vote, giving a single-room house as their address.

His example was of the Karnataka voter database that was finalised in 2024. We examined the new voter database that the ECI has ordered to be prepared for the entire country to weed out the problems of the existing one.

In our previous report, in this new voter list of just one constituency of Bihar, Valmikinagar, we unearthed over 5000 dubious or duplicate voters in the draft electoral rolls who also hold voting IDs in Uttar Pradesh.

In this investigation and data analysis, we looked at people being dubiously registered at the falsified addresses.

Only a door-to-door analysis can establish whether the 80,000 voters registered in this way are legitimate voters or dubious. The ECI had promised such door-to-door verification under the SIR.

One of us checked four polling stations in Pipra, and each had one house where scores of voters were registered under a single roof.

We first checked the most preposterous cases: Two adjoining booths, 320 and 319 in Galimpur, Pipra, where 459 and 509 individuals were registered to vote under houses numbered 39 and 4, respectively.

The voters had no clue how or where they had been put on the draft voter list. They heard it first from us and were astonished to find out that hundreds of voters in their village had been registered to vote under a single roof.

“How is this possible?" asked a shocked Shivnath Das, father of Amit Kumar, one of the 509 people registered to vote under the same roof, in Booth 319, Pipra.

“People live together in the village, with love and brotherhood, but everyone has separate houses. People of the Musahar community live separately, while people of the Das (Baniya) community live separately. Similarly, people of the Jhal (Brahmin) community live separately,” Das explained.

Questions tinted with anger, curiosity, and shock ran afire amongst villagers in Galimpur, when our correspondent continued to make queries. “How is it that members from the Manjhi-Musahar caste and Brahmin-Baniya caste are living together? This is the mischief of those who fill the names and numbers,” said one voter.

Galimpur is in rural Bihar, where communities are still deeply fractured by caste. Here, the state election officials’ “audacity” to put the most disadvantaged of Dalit communities like Manjhi and Musahar under one roof, with Brahmin and Baniyas, even if only on paper in the voter roll, astounded villagers.

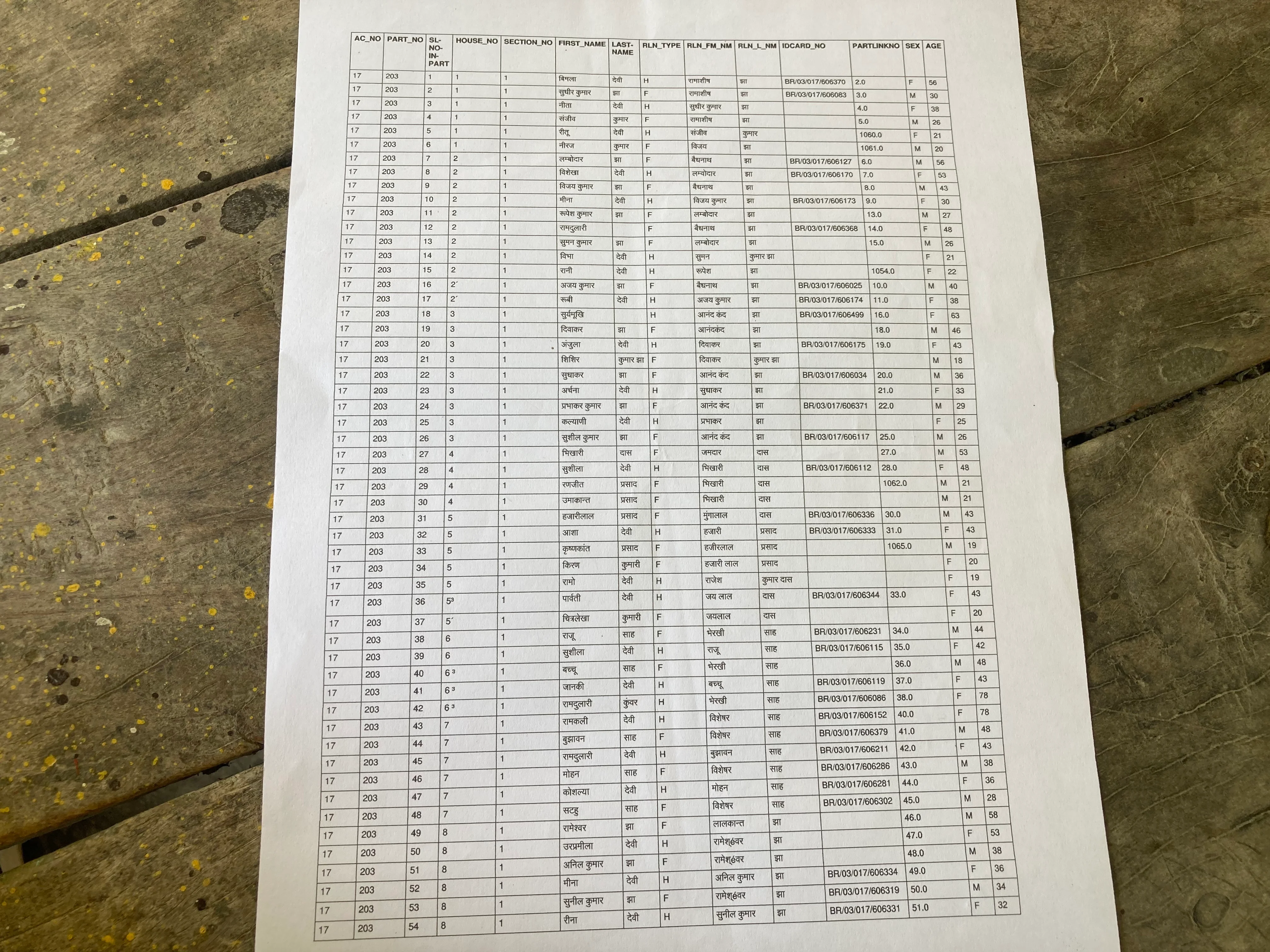

Ajay Kumar Jha, who had been registered by the ECI as one of the 459 voters living under one roof in Booth number 320 produced the electoral roll from the 2003 special intensive revision to show that this practice of dubious and fake addresses was not the norm in 2003. The 459 voters had different addresses in the 2003 list.

Twenty-two years later, in the name of creating a ‘clean’ voter list within two months, and with greater use of technology and manpower, the ECI has done worse.

None of the four addresses that the ECI had registered with hundreds of voters exists, our ground check has ascertained.

The Notional Address

Rural areas and people living in temporary housing, shelters, or the homeless in cities often do not have addresses with house numbers. The ECI has a standard method to address such situations. A notional number is given for such voters with ‘N’ prefixed to the number.

In any subsequent revision of the voter list, the booth-level officials are required to stick to the number given or update it only if the person has moved. This is important for the door-to-door exercise of verification to serve its purpose.

We found that the ECI officials across Bihar have not even followed that system this time around for SIR, making the voter lists, in several cases, even more substandard than the earlier ones.

Next, we visited Booth 196, where 104 voters have been registered under a non-existent house numbered 2.

The story repeated itself. People had not filled their forms; officials had. And they surely did not all live in a mansion in the village that could provide for more than 100 people.

Jadulal Shah, from booth 196 of Pipra constituency, explained, “There is no numbering on any of the houses here. Our entire family, including my son and daughter-in-law and my wife, all live in the old house. In such a situation, we cannot tell you exactly how and why this happened.”

Shah recollected that he had not filled out his enumeration form. It was filled by the election officials. “Only Aadhaar was taken in the name of documents, and for some, they asked for photographs. The rest of the forms they (the department) filled themselves and took away,” he said.

Our correspondent repeatedly tried to contact election officials at the booth and district levels, but actively avoided communication. If and when some did become finally accessible, they refused to comment.

In two other booths that our correspondent checked and found that booth-level officers of ECI had written the name of the ward or the gram panchayat in the place for addresses.

In haste, the standard and old ECI practice of giving notional addresses, had been done away with.

We found that several of the 80,000 bundled into fake addresses or wrong addresses had also been listed in the same fashion in the January 2025 final voter list. The SIR has not improved upon it.

The fact that the 80,000 voters we identified have more or less remained on the electoral rolls in the same botched manner as January 2025 suggests that the SIR has not served the purpose the ECI claimed it would.

Blame ECI or the booth-level official?

In the thirty-day sprint to distribute and collect enumeration forms, booth-level officers had only just enough time to superficially carry out the ECI’s diktat. Booth-level officers that our correspondent spoke to confirmed this repeatedly. For Booth 319, our correspondent traced the booth-level officer Shashi Ranjan Jha.

He acknowledged that booth-level officers had filled the enumeration forms in many cases. He said they were not to blame for the mess with the addresses that we detected.

“Ever since I became a BLO, I have seen many mistakes and got them corrected, but many things were done in a hurry…(For SIR). We had to stay awake all night to upload documents to the Election Commission website. The website did not work during the day. Anyway, no one here has been allotted a separate housing or holding number. Even if it has happened, no one remembers,” he said.

BLOs were just scrambling to get things done. Several of those who spoke to us (and preferred to be anonymous) said they were not properly briefed on how to solve issues regarding false and wrong addresses.

Jha lamented, “We understand that the BLO is the primary and weak link in this entire process, so all questions have to be asked from him, but who will understand his compulsions? It is easy to hold him responsible for everything, but who will understand his problems?”

ECI formally responded on August 16 to the increasing outcry over its faulty electoral rolls. It passed the buck of responsibility for its botched voter lists to political parties, for not informing the Commission to rectify the lists in due time. "It seems that some political parties and their Booth Level Agents (BLAs) did not examine the Electoral Rolls at the appropriate time and did not point the errors, if any, to SDMs/EROs, DEOs or CEOs," it noted.

.avif)