New Delhi: I go to a nearby grocery store to buy some biscuits. I'm told regular biscuits aren't healthy. In one section of the store, I find biscuits that the processed food industry sells to people like me who are looking for ‘healthy’ options. One is marked loudly on the front of the packet: “20% protein”. At the back of the box, in tiny print that the naked eye can’t read with ease, the company acknowledges that every 100 grams of biscuit contains 13 grams of sugar. That is more than 3 teaspoons of sugar.

This is the cookie that crumbles in India’s food labelling regime: companies can boast of protein, fibre, or vitamins on the front of pack labels, while pushing sugar, salt, and fat numbers to the fine print at the back of the package. Even so, the presence of proteins does not mitigate the problems caused by consuming excess sugar.

Poison baked into a piece of cake or mixed in a protein shake is still poison.

One in nine Indians is estimated to live with diabetes, a 2023 study published in The Lancet tells us. That is approximately 101 million people.

I recommend that you read the rest of the story, keeping these two sentences in mind.

Here is the story.

In 2014, experts at the Union government’s apex agency, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), recommended that processed food in India should be sold under a clear and strict Front-of-Pack Labels (FOPL) policy. Consumers deserve to know upfront what good and bad ingredients they are ingesting, FSSAI’s experts concluded.

The FSSAI reports to the Union ministry of Health and Family Welfare and is empowered by law to regulate food quality in the country, including the Rs 30 lakh crore worth of products that the processed food industry sells in India annually.

The experts’ recommendation was in line with the shift in global standards. Developed and developing countries such as Mexico, Chile, Argentina, and Finland have successfully enforced these regulations in forms of warning labels. In these countries, the FOPL warning labels have been implemented, achieving significant success in protecting public health. A warning label directly flags the bad ingredients like, high fat, high sugar, on the front of the pack, helping consumers make informed choices.

Eleven years after the food safety body first proposed FOPL, India still does not have any. The government has dragged its feet for over a decade at the cost of people’s health and in favour of corporate profits.

The closest the FSSAI and the government ever came to putting a FOPL policy in place was in 2022, when it advocated a health star rating method that Australia and New Zealand favours. The Indian version of the health star rating idea that FSSAI propounded did not offer blunt warnings to consumers about unhealthy ingredients.

Then that too fell into a limbo.

Now, forced by the courts, more than a decade later, the government is likely to bring in a FOPL policy sometime soon. “Leaks” from the government suggest that FSSAI will altogether scrap star ratings and go back to the drawing board. Kicking the can down the road, yet again.

This is the story of how, after more than a decade, dozens of stakeholder meetings, reams of official paperwork, crores spent on dubious studies, and surveys, lobbying by the industry and head banging by the industry watchdogs, India has got nowhere closer to dealing with the burgeoning public health risk from unchecked consumption of fat, salt, and sugar foods. Reports detailing FSSAI’s policy drafting blunders on this issue have been tracked, and published over the years. They can be read here, here, and here.

The Indian government and its food regulator, FSSAI, have dawdled. Meanwhile, over 28% of Indian adults are now overweight or obese, and one in four adults is diabetic or pre-diabetic. Once unthinkable, even (ages 10–19) are pre-diabetic now. According to the Indian Council of Medical Research, 56.4% of India’s total disease burden is now due to unhealthy diets.

Where it all began

It all began back in September 2013, when the Delhi High Court ordered the FSSAI to formulate guidelines for "wholesome, nutritious, safe, and hygienic food" for school children, following a 2010 Public Interest Litigation (PIL) by the Uday Foundation to ban junk food in and around schools.

After the issue languished for several years, in 2018, the FSSAI drafted a set of labelling rules that mandated a red mark to be displayed on food products that were High Fat, Sugar, Salt (HFSS). A clear, easy to alarm warning.

Immediately, the industry pushed back against these regulations. In the same year, speaking at a national consultation on food labelling regulations, Pawan Agarwal, CEO, FSSAI, said, “The pre-draft was earlier sent to the Health Ministry for finalisation. However, industry stakeholders have expressed concerns. So we have decided to set up a panel of experts with health and nutrition background to look into the draft regulations.”

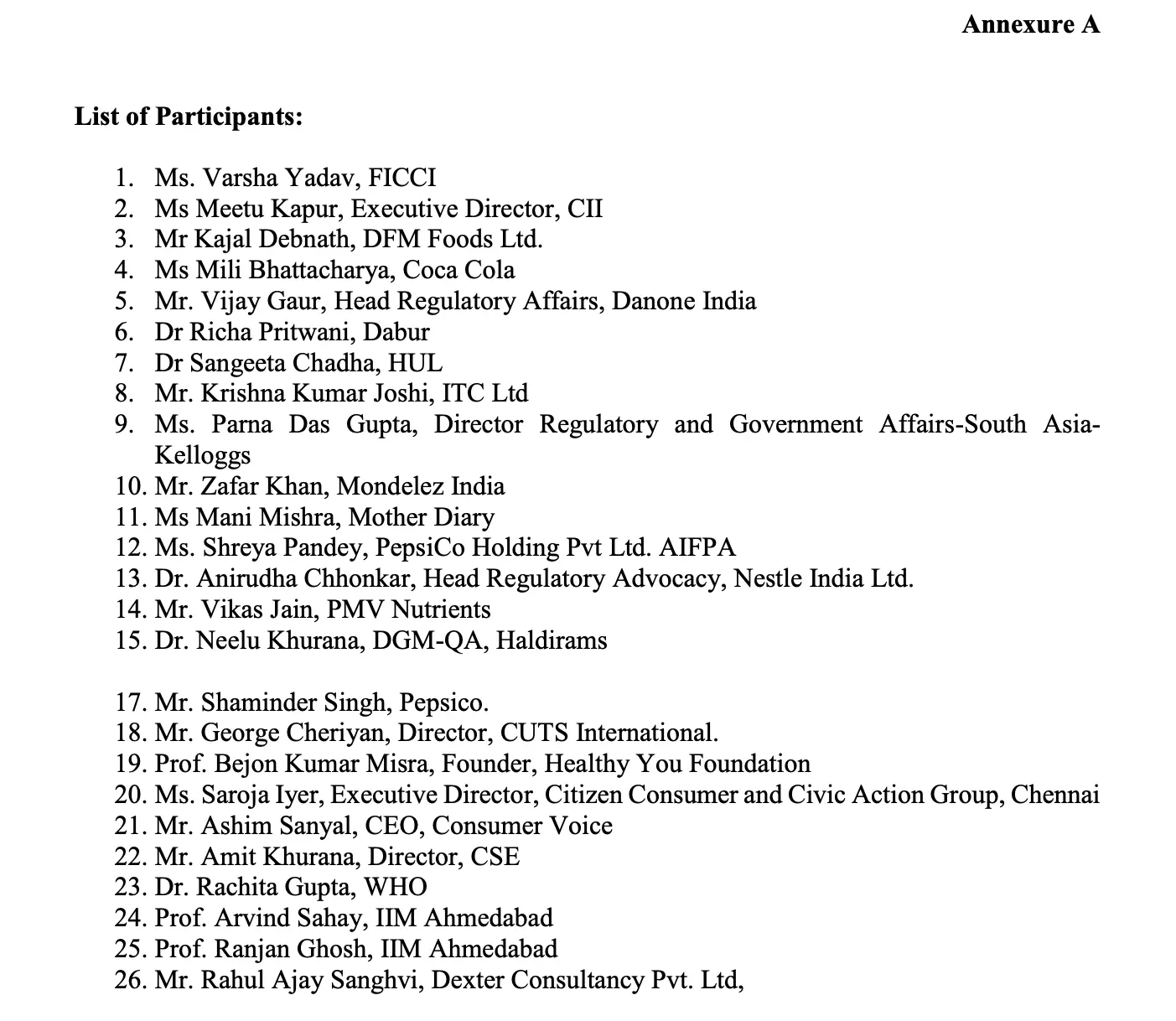

In other words, industry lobbying catapulted India’s carefully crafted warning label plan back to the drawing board – foreshadowing a dangerous pattern to be seen in stakeholder meetings that followed on the FOPL matter. Industry representatives routinely outnumbered consumer groups in ratios of six to one, giving food giants like PepsiCo, Coca-Cola and Haldiram a chance to sit at the table and influence food safety policy. These companies were present to shape regulations meant to govern them. In allowing this, the regulator turned a safeguard into a negotiation.

A star rating and a warning label serve two very different purposes. The star converts a food’s nutrients into a single score of stars; leaving the shopper to infer what that means for their overall health. A warning label does the opposite. It spells out in plain terms, if a product is high in sugar, salt, or fat. For someone living with diabetes or hypertension, the difference matters: one system reduces the risk to a star, the other spells it out. For the food industry, the warnings cut directly into sales.

What happened next

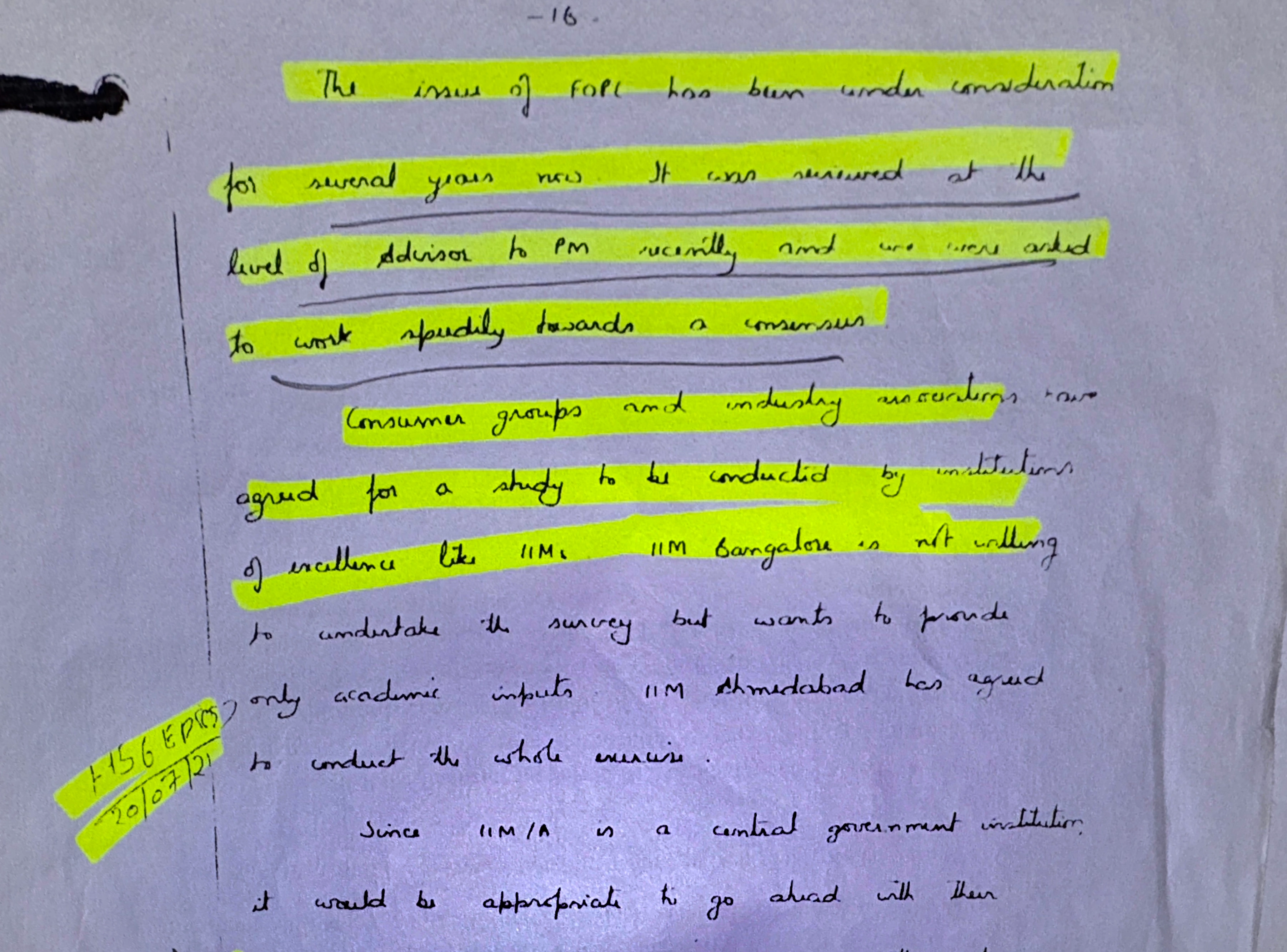

On June 30th, 2021, the sixth stakeholder meeting was held to decide the future of FOPL. The matter had been reviewed at the level of Advisor to the Prime Minister, and the FSSAI was under pressure to come to a speedy consensus.

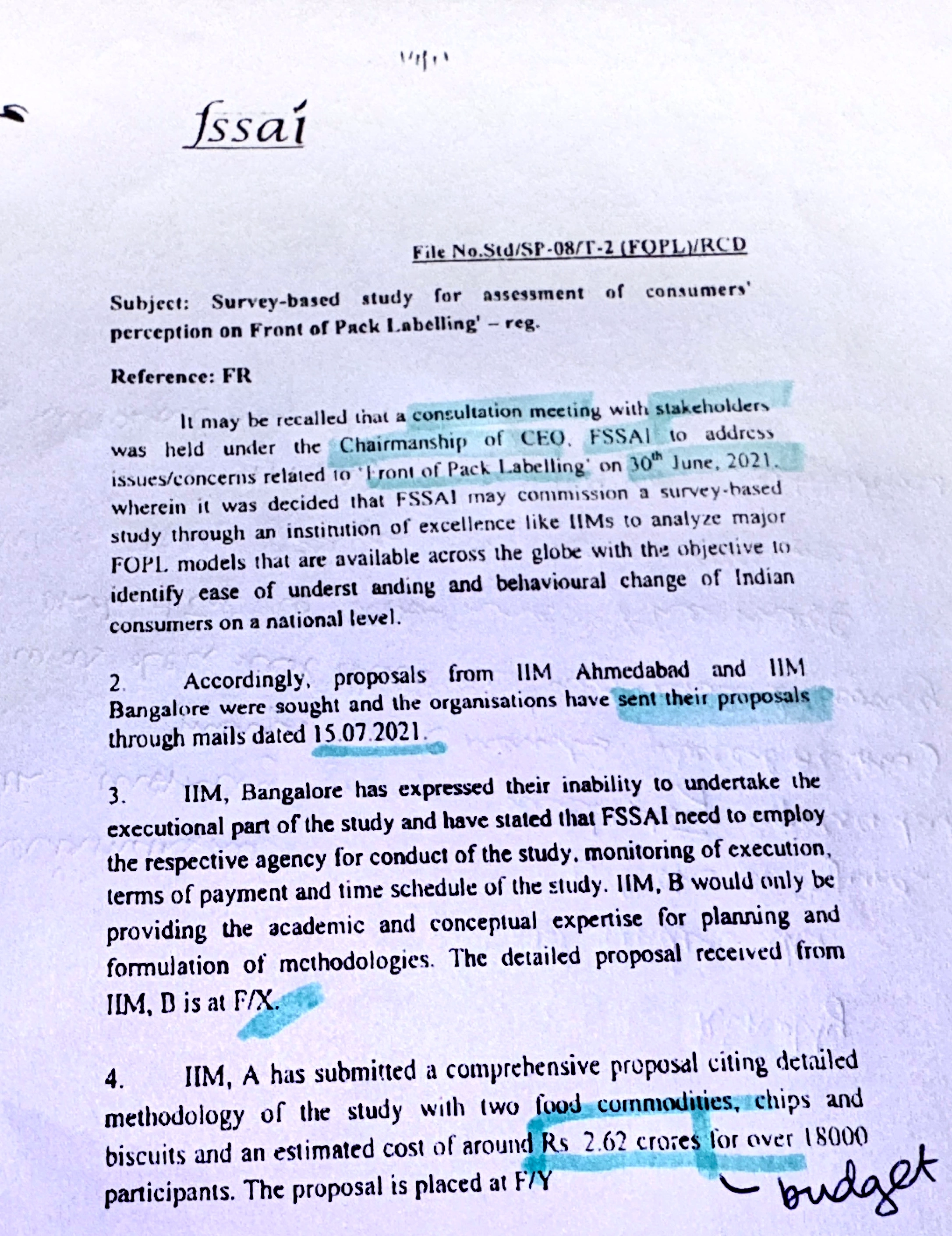

Industry called for an “independent” study by an institute of excellence. Instead of entrusting this critical health-policy study to a medical institution like AIIMS, FSSAI chose a business school – IIM Ahmedabad to undertake this exercise.

In turn, IIM Ahmedabad outsourced the survey to Dexter Consultancy, a data management firm with its headquarters in Ahmedabad. The FSSAI made payments of approximately 2.6 crore rupees for the purpose of this survey.

In its premise, IIM agreed that for an FOPL to be effective, it needed to have “the ability to affect purchase decisions. Its data showed warning labels FOPL system deterred purchases more effectively, yet its conclusion pivoted to something entirely different and more industry-friendly, citing ‘ease of understanding’.

Public health experts repeatedly flagged this study as a conflict of interest, sending multiple letters to the Prime Minister’s Office, warning that the IIM-A study was methodologically unsound and unfit to guide a major health policy.

Draft regulations for Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPNL) were released by FSSAI on September 13th, 2022, along with the proposed "Indian Nutrition Rating" (INR) system, motivated by the IIM study.

According to George Cheriyan, (Director, CUTS International), the thresholds set under the INR system were astonishingly lenient in comparison to WHO-SEARO’s recommended Nutrient Profile Model (NPM) for South-East Asia. They allowed up to 3.5 times more sugar, 450 mg of sodium, compared to the WHO’s 250 mg.

FSSAI chose a model of FOPL with little evidence of success: the Health Star Rating (HSR) used in Australia and New Zealand, which has not demonstrably reduced junk food consumption, one of the reasons was due to its inability to clearly represent the relationship between processed foods and health outcomes. FSSAI had devised an Indian version of it, called the Indian Nutrition Rating (INR), in 2022. The government was proposing marking processed food products with an algorithm that would rate the food between 1-5 stars, taking into account both the positive and negative nutrients in a product.

FSSAI invited everyone, including the civil society watchdogs and the industry, to send in comments on the proposed policy. In the two-month phase, FSSAI received 14,000 comments, after which further movement on the policy was stalled indefinitely.

Civil society and public health experts were vocal in calling INR an ineffective method to warn consumers against bad ingredients. Several have made their inputs public, which can be found here, here, and here.

To understand the crux of their argument, one can use this example. Consider the average biscuit made of refined flour, sugar, and palm oil, which contains 28.5 grams of sugar. Ideally, it should get no positive rating at all. Under a warning regime, it would simply be labelled with a red alert as a product which is “High in Sugar” and “High in Fat” to warn consumers. But under INR’s nutrient algorithm, if the manufacturer fortifies those biscuits with a bit of fruit pulp or some nuts (adding a smidge of fiber/protein), the product can earn extra stars, adding a healthy halo to an otherwise unhealthy food.

Besides the civil society critiques, who else had written to the food safety agency? What were their comments? The FSSAI wouldn’t tell. Even under the Right to Information Act.

Nutrition Advocacy in Public Interest (NAPi) even provided FSSAI with a framework to evaluate the 14,000 comments objectively. “The number 14,000 is a distraction; the key is to categorise, not count,” said Dr. Arun Gupta of NAPi. He suggested that industry submissions be given minimal weight (0–2/10) due to their vested interest, and independent scientific evidence be given the highest weight (9-10/10). This is to prevent the policy from being hijacked by the sheer volume of industry comments.

The FSSAI requested extensions on reviewing the comments, citing the need for extensive pan-India consultations. Predictably, it appointed another Scientific Panel to review the comments and has yet to share any information regarding the same.

Frustrated with delays, in 2025, one nonprofit –3S (Students’ Science Society) and Our Health Society –filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court, seeking judicial intervention to force the implementation of effective FOPL, specifically warning labels on unhealthy foods. The PIL argued that Indian consumers needed protection from the epidemic of lifestyle diseases, and clear warnings on high sugar, salt, and fat foods were essential.

Marking a significant development, the Supreme Court of India took cognisance. On 12 April 2025, the apex court granted FSSAI’s expert panel three months to finalise FOPL recommendations. When FSSAI had not delivered by July, the Supreme Court granted another three-month extension from mid-July to mid-October to finalise its recommendations on FOPL, expressly mentioning the move to introduce mandatory warning labels.

Still keeping us in the dark

A decade of holding several deliberations and spending public money, Indian shoppers still face supermarket shelves without a single mandatory warning label on high fat, salt, or sugar foods from the FSSAI. The body responsible for food safety in a country, where non-communicable diseases cause 60% of deaths, had to be pushed by activists and repeatedly reminded by the Supreme Court to issue simple and clear warnings.

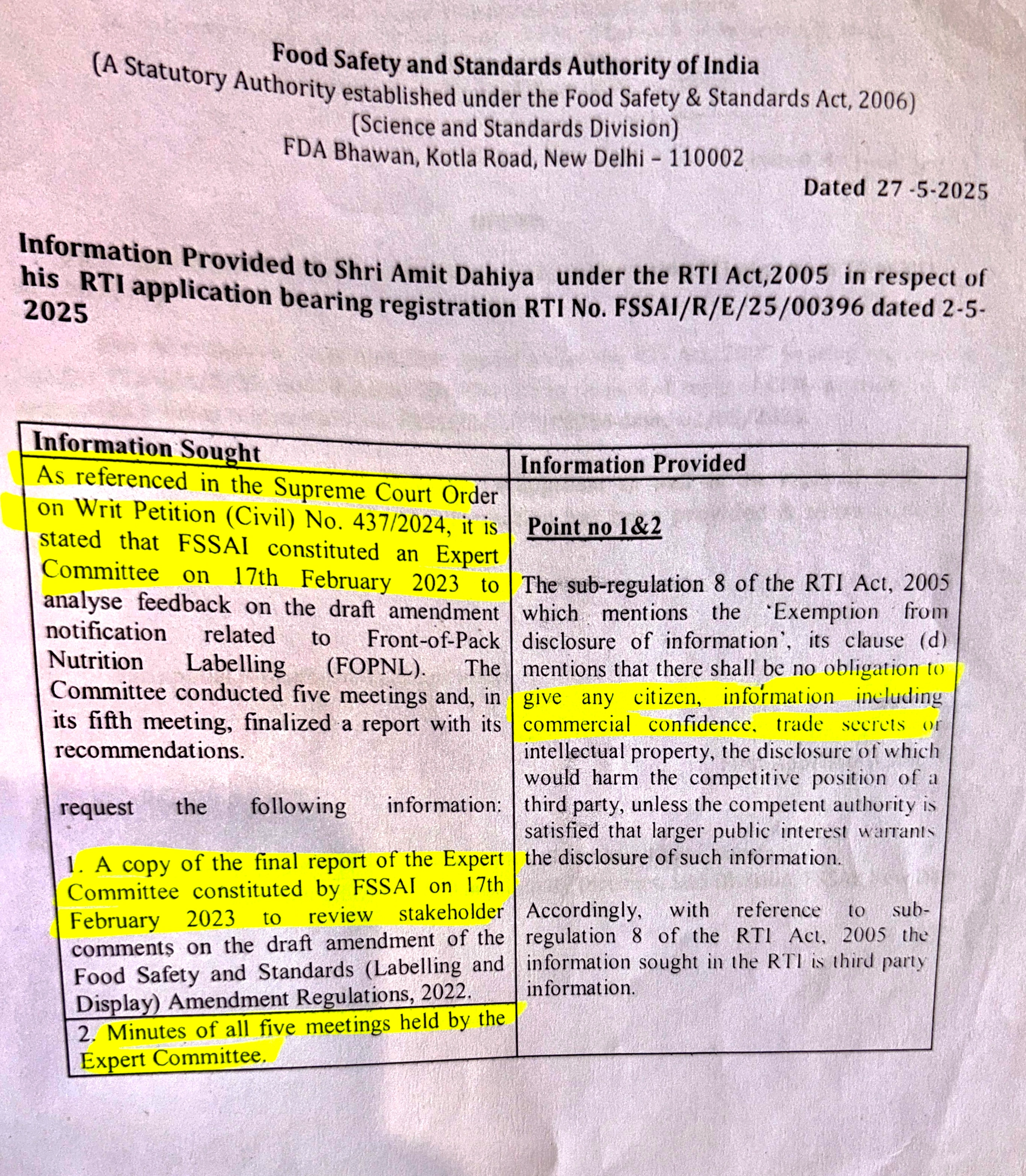

In May 2025, citizen Amit Dahiya filed an RTI seeking the minutes and final report of the Expert Committee that FSSAI itself had cited in the Supreme Court. These documents would have shown the Expert Committee's initial deliberation on 14,000 comments received on the draft FOPL policy. It would also tell reasons why implementations of the policy appear to have been stalled indefinitely. On 27 May 2025, FSSAI refused, invoking Section 8(1)(d) of the RTI Act, a clause meant to protect “commercial confidence” and trade secrets. In its response, the regulator argued that committee deliberations on food labelling were “third-party information.”

Earlier RTIs into FOPL have met with similar evasions by FSSAI. When asked how the Indian Nutrition Rating was designed, FSSAI responded only with generic references to “global models” and WHO guidelines, admitting it had been “suitably modified” but never disclosing how or why.

Together, these denials amount to a withholding of information directly tied to public health. By stretching a loophole in the RTI Act, a statutory regulator has treated life-and-death nutrition standards as if they were corporate trade secrets – leaving consumers, doctors, and policymakers in the dark.

October is upon us, and the credibility of FSSAI hangs in the balance. “The FSSAI is at a crossroads,” Dr. Gupta said pointedly. “It can either be remembered as the regulator that empowered millions of Indians to make informed choices, or the one that capitulated to food corporations.” This choice is not just about labels on packages; it reflects whom the regulator truly serves. The next FSSAI decision will decide if India continues down a path where ultra-processed foods fuel diabetes and cancer unchecked, or whether the regulator finally draws a line in defence for public health.

Questions were sent for this reporting to FSSAI and IIM Ahmedabad, and CII. They had not replied till the time of publication. The story will be updated if they do.

.avif)