Kolkata

The Conclusion

The Reporters’ Collective has established, with granular evidence, how the Election Commission of India (ECI) ran the voter roll revision in West Bengal with unfettered discretion. It changed rules and regulations through the course of the revision exercise. It trammeled over the powers of the statutory officials in charge of voter rolls in the assembly. Midway, it superimposed election officials from Kolkata to districts undergoing Special Intensive Revision. The statutory decision-making authorities were either turned into rubber stamps or rendered powerless intermediaries.

The ECI in West Bengal did not run the SIR in a vacuum of rules, rather it imposed a cascade of orders that kept bending and morphing the process to a point where officials administering the process could not keep up. None of these intermittent orders were made public.

While some changes to the SIR were communicated to local officials in writing, personnel were mostly subjected to an overwhelming flux of crucial instructions via informal channels. These included instructions on dedicated WhatsApp groups and diktats issued orally by the Chief Electoral Officer in Kolkata during video conferences. These informal directives often trailed rapid, real-time updates to the ECI’s centralised software, which frequently imposed new terms, norms, and regulations on state officials without prior notice.

As part of this report, The Reporters’ Collective, for the first time, is revealing the entire set of written orders passed by ECI for voter roll revision in West Bengal up to January 23, 2026.

Many of these formal and informal orders substantively impacted citizens of West Bengal, altering their risks and effort to prove their identities, voting rights and citizenship. All of them whipped the officials in the state to change tack at a moment’s notice to keep up with the ECI’s changing mind while trying to provide a modicum of reasonable predictability to citizens.

Editorials and piecemeal reporting by media, including The Reporters’ Collective, have previously documented sporadic changes ECI brought to the SIR in West Bengal and its impact on the citizens. This investigation is arguably the first attempt to document the entire exercise with evidence.

For this investigation, The Collective accessed a tranche of ECI records. We witnessed officials utilising the software to drive document verification for those summoned to hearings. We watched in real-time as how features were toggled on and off, without prior knowledge, to dictate to state officials the course of the revision. These software-driven modifications did more than just change the workflow; sometimes they stood in contradiction with the original legal order instituting the SIR.

We attended closed-door meetings of state officials working under ECI diktats and spoke to officials over several days in the ECI’s West Bengal office, in two districts, and across four assembly constituencies.

Upon completion of our reportage, we sent detailed questions to the ECI. We had not received an answer by the time of publication. If we do, the story will be updated.

{{cta-block}}

Why It Matters

In a case challenging the constitutionality of the SIR, the ECI has told the Supreme Court repeatedly that, under the Constitution, it can carry out a special intensive revision “as it may deem fit”.

In a recent hearing for the case, one of the two-judge bench, Justice Joymalya Bagchi reportedly said, discretion cannot be untrammeled and unregulated. ECI’s lawyer Rakesh Dwivedi agreed, adding that it should be bound by constitutional limits.

However, oral statements made by a judge during a hearing hold no legal weight, and generic promises only serve to obfuscate what is actually occurring in practice.

Only the operational end part of the judgement carries legal force. The hearings are over. The Supreme Court bench of Chief Justice Surya Kant and Justice Bagchi has reserved the judgement in the case.

While reporting from West Bengal, we read of these legal debates in the Supreme Court in Delhi.

This investigation shows how the Supreme Court’s unqualified agreement with ECI’s argument would bring into place an unprecedented change to how India’s voters are asked to reaffirm their voting rights in future. ECI, the custodian of India’s voting rights, could now become a master of the voter roll.

The Investigation

On January 26, we visited a district in West Bengal that is currently undergoing this unprecedented voter roll revision. To protect the identity of those interviewed, The Collective is withholding the name of the district.

The district, which sits on the border with Bangladesh, has ordered some of the highest numbers of its voters, nearly eight lakh, to be called for additional quasi-judicial hearings. During these proceedings, voters were required to submit extra documentation in order to remain on the voter rolls.

The Electoral Registration Officer was supposed to review each case, almost like one would in a court. And then decide and inform the person if she had made it past the ECIs’ procedural hoops to qualify to vote. By law, an ERO is an officer of the government at the constituency level, empowered under Sections 22 and 23 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, to delete or include a voter once they are independently ‘satisfied’ after conducting an inquiry.

But the ERO’s power to do so had been dissolved by the ECI through a change in the software, called ERONET.

The ERO was now to wait for approvals from senior administrative officers handpicked by the West Bengal election office, called Electoral Roll Observer, and the district electoral officer above him before they could press a button in favour of the verified voter.

The ECI had turned the EROs into a powerless intermediary sandwiched between vetoes by superimposed additional layers of junior and senior officials. Voters were not being told whether they had been approved or not. The ERO couldn’t possibly know. The voters’ fate was 'parked' in a digital holding pattern that required multiple clearances before it could be published on the final list.

Citizens were never told that the 'judge' they queued before had been reduced to a mere conduit, a middleman positioned between the voters and a panel of faceless arbiters.

No written or oral orders explaining this were put out in public by the ECI.

The Commission in Delhi had promised voters a simple paperless exercise to register afresh on the rolls. In the name of making it paperless, the ECI had quietly introduced untested and unaudited algorithms, which were subsequently found faulty. It had followed up with other constant operational changes to the software, turning itself from being a custodian to the master of the voter roll.

As part of our investigation, we visited hearing centers where voters were summoned to produce one of 12 mandated citizenship documents. We also visited the offices of two other Electoral Registration Officers, where we observed ERONET’s administrative interface firsthand and witnessed system changes occurring in real time. Finally, we sat with data entry operators in a Block Development Office to further understand the software’s internal logic for verification.

ECI’s Dragnet

ERONET, the Electoral Roll Management System, is a centralised management interface for local officers. It was developed by C-DAC under the Ministry of Electronics and IT.

Built by a Union government agency and introduced in January 2018, ERONET replaced a disjointed system where state election offices relied on local IT firms. It represented a post-2016 push to centralise electoral management. While the system has undergone several iterations, a recent RTI by The Collective confirmed that the central government’s agency no longer works on it.

Since 2023, the latest version, ERONET 2.0, has been operated by Tata Consultancy Services, India’s bona fide private tech behemoth. The ECI has not disclosed this. We found this from the private company’s annual disclosures to its shareholders.

.webp)

Using the interface, the election officer can digitally monitor the work of its foot soldiers – booth-level officers, access ECI’s national database for voters, or access those on its assembly voter roll.

This interface allowed election officers to manage the revision of voter rolls and additional checks, which happened four times a year, even before the announcement of the SIR. Naturally, the same interface was deployed to administer the SIR process as well. Think of ERONET as an app to mitigate an officer’s workload through smart digital management.

However, unlike most apps in the open market, which are usually beta tested and perfected before being deployed, officials described and showed an ERONET, which was changing on the go, as the rules of SIR underwent further transformation.

A Recap

The ECI has admitted that the SIR is unprecedented. When it began with Bihar last year, the existing manual for revision of voter rolls was set aside.

The manual was exhaustive, providing citizens with a step-by-step roadmap of how the ECI machinery would function during periodic reviews of the electoral rolls. In doing so, ECI held itself to the public account as a custodian of the citizens’ voter roll.

The detailed manual was replaced by a generic overarching order. This order left out the important details of how the SIR would be conducted.

These details came to be known only to officials in Bihar slowly. The Reporters’ Collective accessed these and other records to show how the ECI had removed the important safeguard of detecting suspect duplicates and then getting them verified on the ground.

Then, despite the chaos in Bihar, the ECI announced voter roll revisions in 12 other states, including West Bengal. By constantly shifting the rules, the current nationwide SIR has become fundamentally different from the one conducted in Bihar.

It had initially claimed that identifying and removing ‘illegal migrants’ was one of the key reasons to carry out the SIR. In Bihar, they found none. Now the hunt for them would start in West Bengal and other states.

Without a comprehensive new manual, the ECI altered the terms of the SIR yet again for the next 12 states. Again, detailed step-by-step orders and procedures were not made public. Without these details in public, each state was being pushed to follow different protocols.

The constantly-updated SIR of West Bengal began. There were benign updates, such as the extension of deadlines to complete the initial enumeration phase in West Bengal. Less benign: ECI changed the criteria for who they deemed as ‘suspicious voters’ several times over the course of this exercise in the state.

The first check carried a simple logic. The last Special Intensive Revision was conducted two decades ago, between 2002 and 2004, so those lists will be considered sacrosanct. In Phase 2, all voters did not have to submit one in 12 citizenship documents; they merely had to prove that either they or their relatives were on the 2002-2004 voter roll. Voters, along with their booth-level officers, could do so by submitting part of that roll along with their enumeration form. This exercise was called mapping.

Then ECI decided to check the voters’ submission. By digitising voter rolls and the new data and making the software check them against the other. But per ECI’s own admission, this initial digitisation was faulty as there were “sporadic errors in conversion of the 2002 electoral rolls into CSV.” Several voters were left wrongfully “unmapped”. They would face provisional deletion unless they showed up with their citizenship and other documents during the quasi-judicial hearings.

If ECI hoped to detect a large number of doubtful voters, the results belied their expectations. Only 3% of the voters were marked out as suspicious.

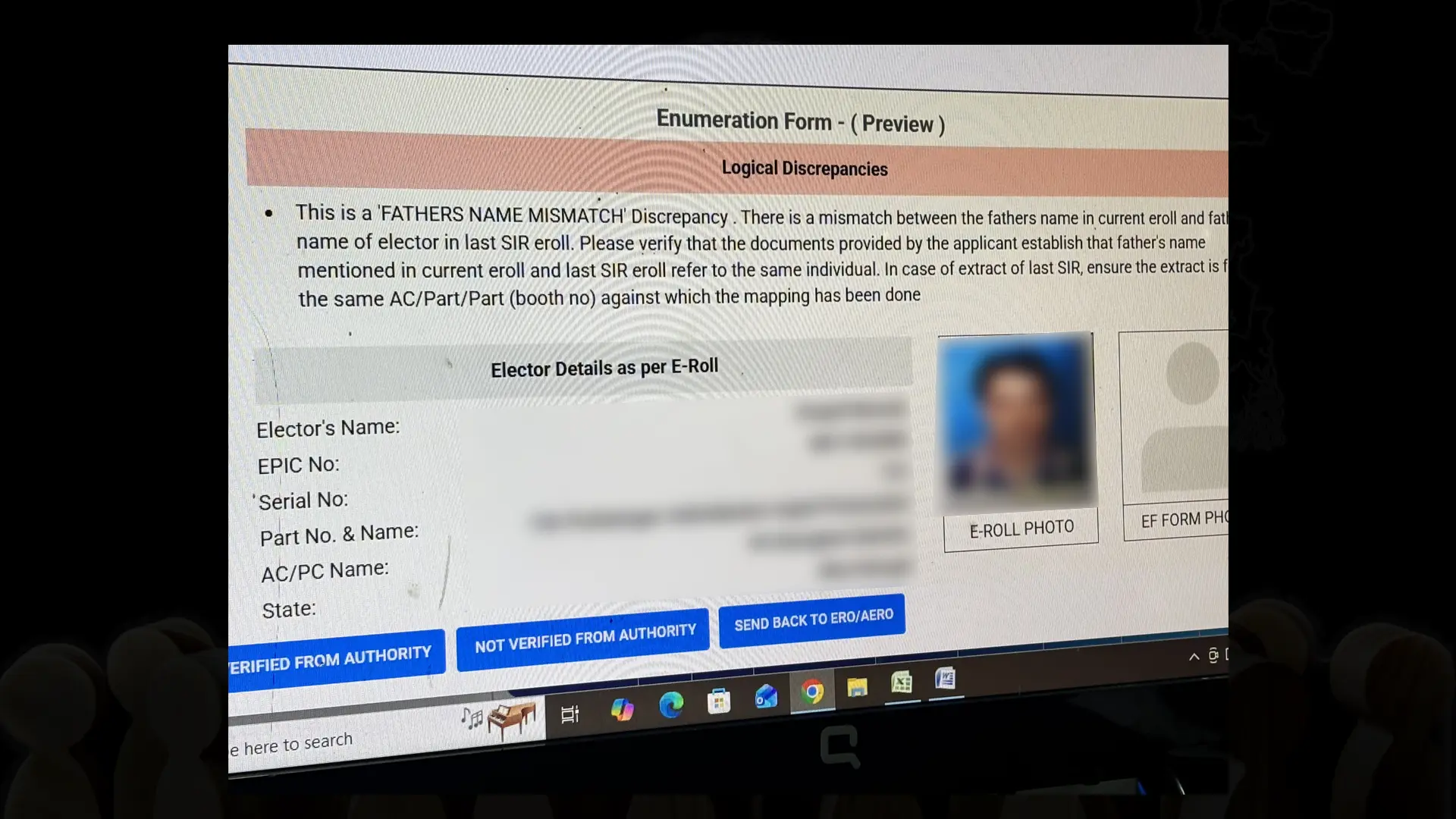

The Commission switched on another algorithm midway through the exercise. This algorithm red-flagged cases from among voters who had passed the first ECI hurdle and got mapped. They would be euphemistically called “logical discrepancies”. In effect, they would be put on the suspicious list too and asked to queue up to prove themselves.

The discrepancies were of five kinds, as per ECI’s new algorithm:

- Differences in spelling between the names in the 2002 in Bengali script and in the 2025 draft voter rolls in English

- More than six voters had linked themselves to a single ancestor from the 2003 list;

- The age gap between a voter and their parent fell outside the 15-to-45-year range;

- A cited grandparent was less than 40 years older than the voter;

- The gender of the voter did not align with the name provided.

So a person named ‘Chowdhury’ once, and ‘Choudhary’ in another record, was a ‘logical discrepancy’. Similarly, if Fatima Begum became Fatima Bgm over the years, her name too would be flagged as a logical discrepancy.

ECI’s software searching for ‘logical discrepancies’ markedly increased the number of voters ECI found suspicious, from 32 lakh to now 1.5 crore.

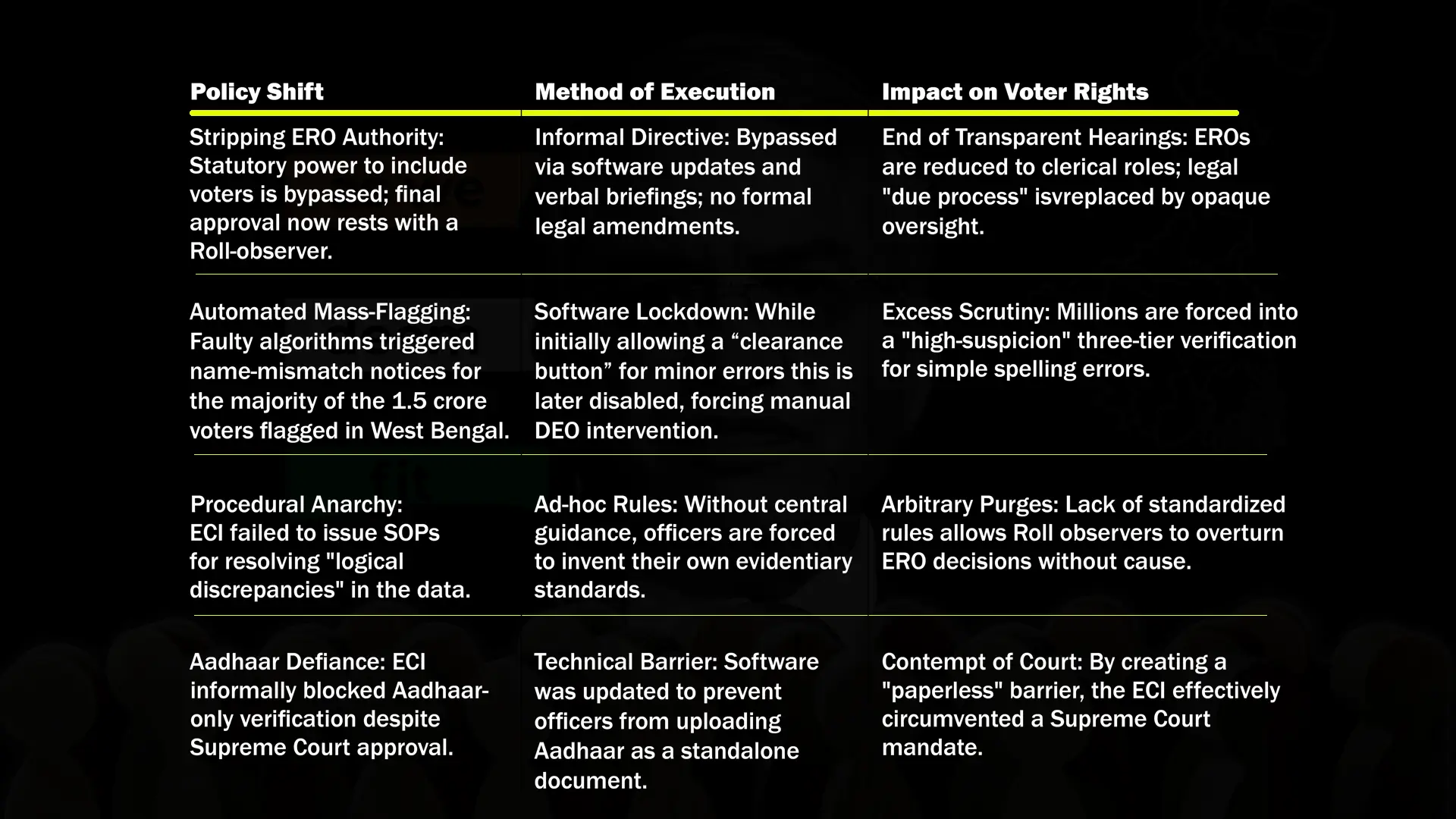

An analysis by the Sabar Institute across five booths in the Bhabanipore Assembly constituency reveals that Muslim voters were disproportionately flagged by this new filter. In booth number 116, for instance, Muslims accounted for only 11% of voters marked 'Absent, Shifted, or Dead' (ASDD) during the initial physical enumeration phase. The 'Unmapped' (UM) share for this booth was approximately 30%. Yet, in the final software-driven flagging for 'Logical Discrepancies,' a staggering 72.2% of those flagged are Muslim. This disproportionate trend repeats itself across all five analysed booths.

As the number of suspicious voters ballooned, ECI kept updating its administrative software to accommodate this increasingly protean exercise. Instructions to navigate new features were provided on online video conferences or WhatsApp groups. What was missing was any paper trail instituting these informal orders that were baked into the software over time.

A Software Morphing

By the time we had started reporting on ECI’s voter verification in Bengal, after Republic Day, the Commission had rushed through the majority of hearings in the state. Unmapped voters and those with logical discrepancies were called en masse through notices issued perfunctorily. Each electoral officer and their deputies were listening to hundreds of cases each day.

By the time we caught the hearings from the ground, in the last week of January. Officers were rushing to complete all hearings by their internal (again unannounced) deadline, February 2.

The hearings were quasi-judicial only in name; an electoral officer was not allowed to decide on a voter’s inclusion or deletion at that instance when the voter is present. They served as a mechanical exercise of document collection, with the final verdict becoming clear only once the final voter list is out.

At the fag end, the majority of voters attending hearings at the centre we visited were those red-flagged for logical discrepancies. In this assembly constituency, the ERO had completed all hearings for unmapped electors weeks before. Of the nearly 50,000 notices that he issued in his assembly constituency, nearly 45,000 were for logical discrepancies. A cursory glance around the centre revealed a significant portion of those attending were identifiably Muslim.

.webp)

Following the conclusion of the hearings, we interviewed the ERO at the district office to better understand the process.

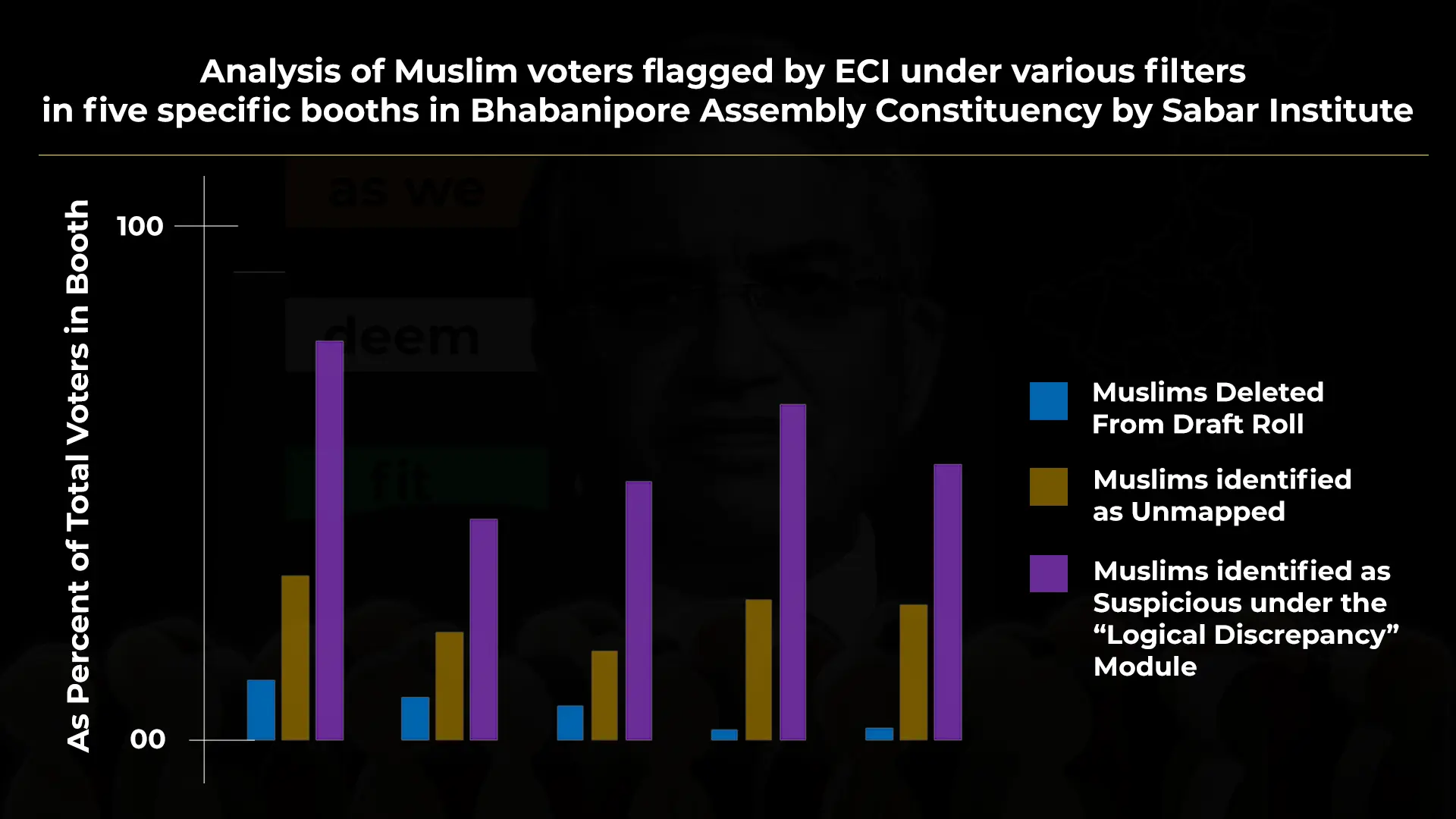

Upon returning to the office, we observed his deputies systematically uploading the day's documents to ERONET. This was a result of a stern directive issued on January 22 by Manoj Kumar Agarwal, Chief Electoral Officer of West Bengal, to district magistrates, instructing that officers must update the portal daily after the day's hearings. This directive was issued after the CEO learnt of significant bottlenecks in document verification.

As part of the interview, the ERO also demonstrated to us, from his login, how they deployed ERONET.

Toggled Off

The ERONET’s interface presents all voters in the assembly constituency in three neat buckets. “Unmapped electors”, “Logical Discrepancies”, and the catchall “Others”, where voters with no red flags are parked, are also pending individual clearance by the ERO.

The name of each elector can be clicked and opened, giving options to upload their identity documents, review them and then institute one of two actions, at least when we review the interface.

- Delete the voter from the list or

- Forward to the District Election Officer for further verification.

The Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) opened the Election Commission of India’s (ECI) software. The button for him to approve the voters whose papers had been verified had vanished. We, too, had seen the option the day before on another officer’s computer.

“These options keep changing every other day,” the ERO told me. “Till this morning, for logical discrepancies with name mismatch, ERONET was allowing me to verify the elector by myself. Now, when I open ERONET, that button has disappeared. Now, these have to be approved by the DEO.”

The change in the software meant that the voter’s case and identity papers had to go through the District Magistrate or the DEO's office before returning to the ERO, a mere rubber stamp.

Then the CEO of West Bengal, ECI’s top official in the state, created yet another step: the software would only clear a voter for final publication once a micro-observer and a special roll observer had also reviewed the file and individually pressed the verification button for each suspect voter.

Quietly, ERONET’s interface was updated, adding yet another toggle, a button for the special roll observer and his deputed micro-observers.

Only when they pressed yes for each and every individual, would the voters be parked for final publication. While we were on the ground, ERONET logins were still being created in real-time. Only six of the two dozen officials assigned had functional access at the time of our reporting.

The election officer showed us the scant list of voters who had cleared the first two steps of verification; all were now pending verification by the micro-observers and the special roll observer (of whom only one is appointed for final verification). This was the situation just a fortnight before the scheduled publication of West Bengal’s final voter roll.

We accessed the compendium of instructions sent from the West Bengal CEO’s office to the district magistrates.

We are making them all public.

Across two dozen memos, the ECI had failed to outline the specific checklist or criteria by which this final arbiter would clear a voter for inclusion. CEO West Bengal shared two written diktats with the district officials to institute the inclusion of roll-observers in the SIR process. The first was an acknowledgement only in passing within the CEO’s directive on January 22. That memo, which mandated that election officers accelerate the uploading of identification documents, stated:

'You are aware that super checking by the District Election Officer, Roll Observers, Special Roll Observers, and the Chief Electoral Officer... is a mandatory prerequisite for seeking ECI approval for the final publication of the voter roll.'

We searched for any other written order defining the duties of these special roll observers, but found nothing. The only clue was the ECI’s original order from October 27. In that document, the Commission stated that observers would only 'super check' the work of local officials by reviewing only a sample of 250 voter forms. This is a complete contradiction to the role they are actually playing now.

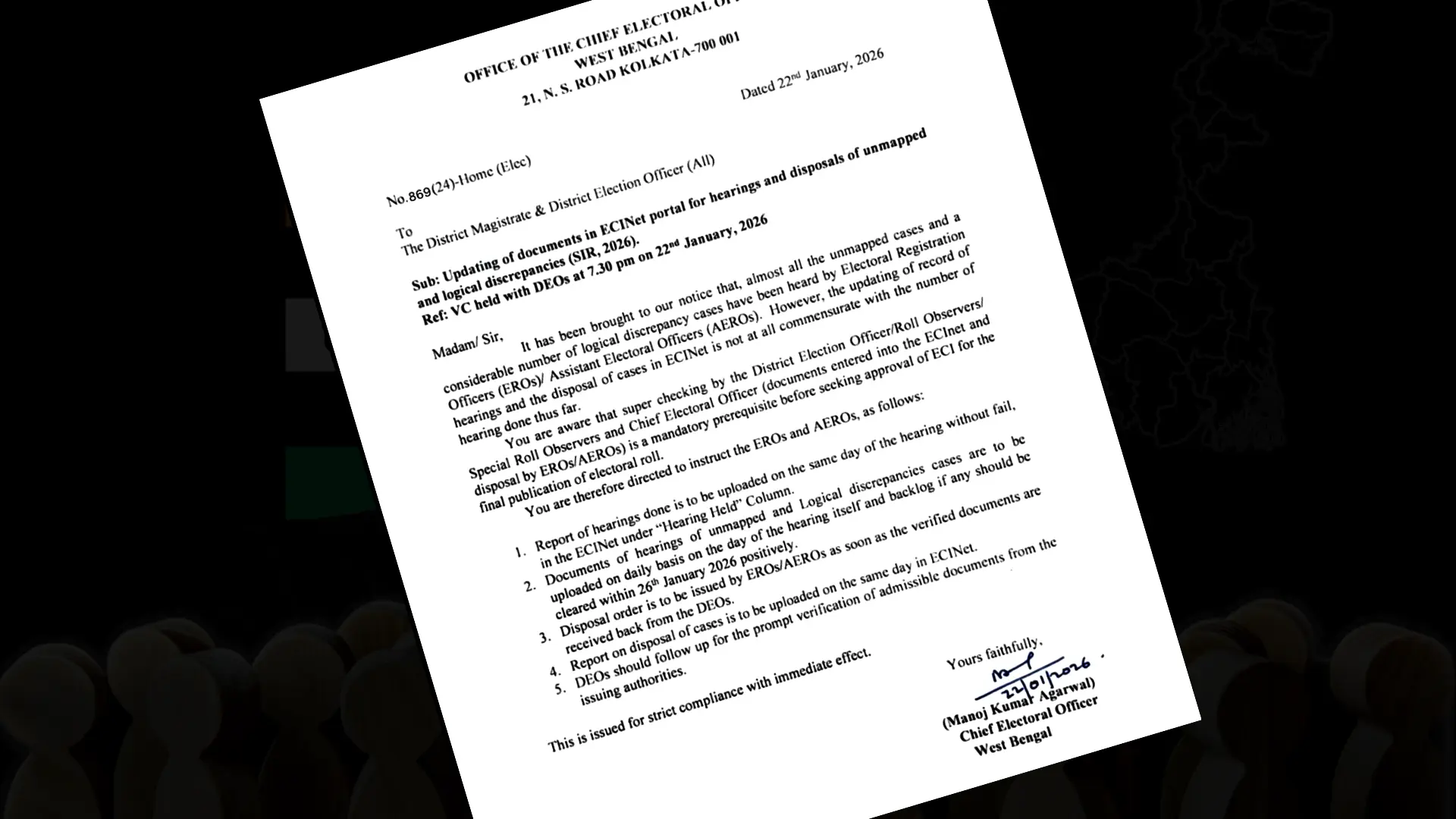

On January 23, the ECI injected another team of officials into the process. The team of handpicked ‘observers’ would be supported by 25 officers each in every district. The term ‘observers’ belied their real role. They would hold veto over each elector cleared by the officer empowered by law, the ERO.

.webp)

While interim steps and daily instructions issued via oral orders during video conferences were kept off the record, ERONET was updated and transformed by ECI from Delhi to hard-code these requirements into the workflow.

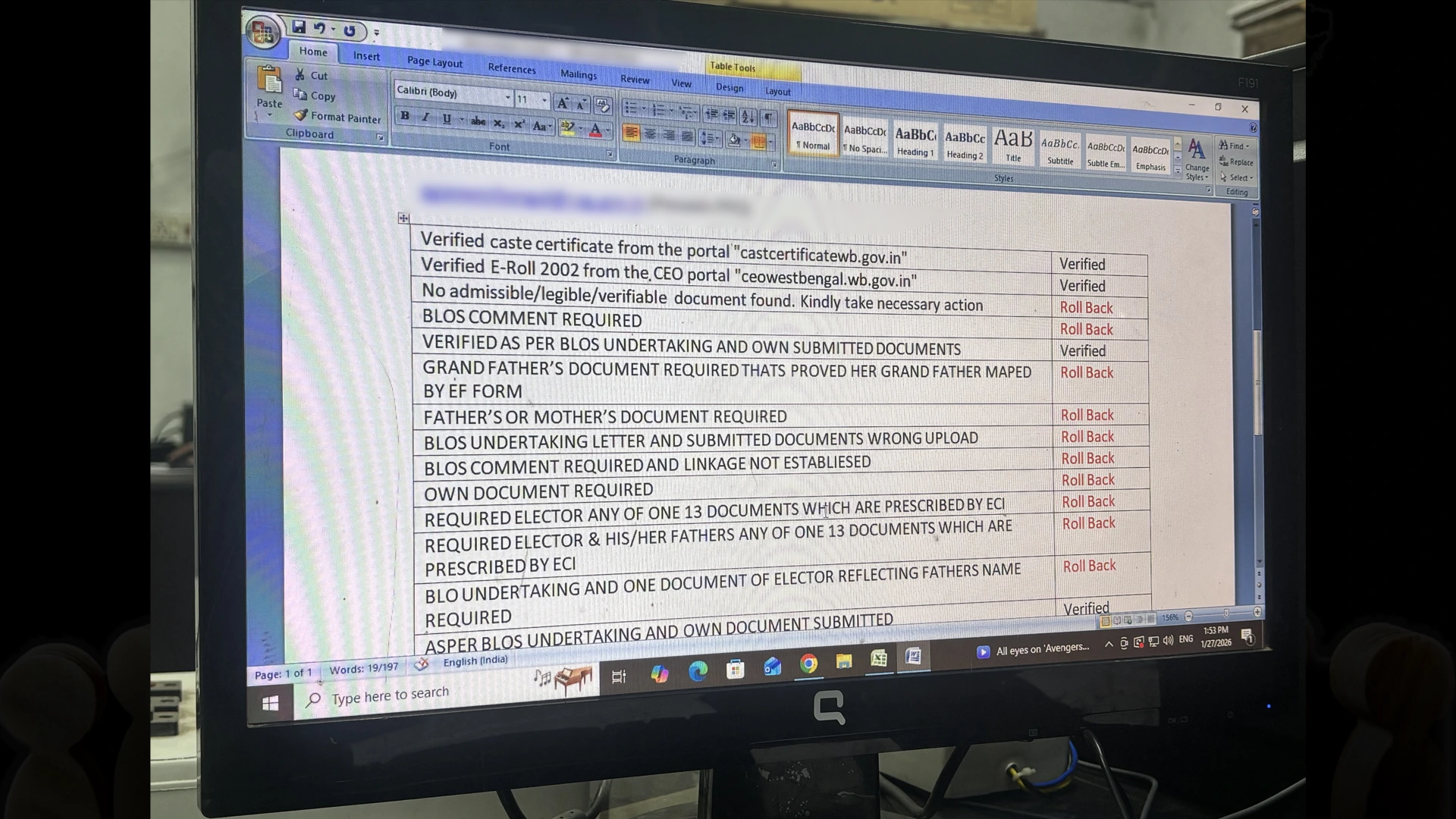

Without written checklists or instructions, officers at the district level brainstormed how to deal with document verification.

Take the case of the mandatory clearance by the District Election Officer. A district in Bengal comprises five to seven assembly constituencies. The district’s highest administrative officer, which is the district magistrate, was quickly made into the intermediary euphemistically to ‘conduct document verification’ or check the assembly ERO’s work. Once cleared by DEO, the voter goes back to ERO to be cleared yet again. Again, missing from this step were detailed rules for how the DEO should conduct the verification.

A single magistrate cannot verify thousands of red-flagged voters. Multiple DEO logins were set up, and data entry operators were deputed to work on the DEO’s instructions to clear his docket. We visited one such DEO facility.

ECI’s New Lord of Voter List

Adrija (name changed on request) is one such data entry operator we interviewed. A recent B-Tech graduate, she had been reviewing 300 to 350 cases each day. That day, too, she had as big a load of cases to clear.

The ECI had passed the powers to the DEO to decide the fate of voters but did not tell them how to. So, this DEO office had come up with its own set of options. These were displayed on a screen in front of Adrija.

The complicated process didn’t often leave her the option to say merely yes or no while verifying the documents uploaded by voters as evidence of their voting rights.

Adrija was required to get a confirmation from the issuing authority for each document uploaded as evidence by the voter. For instance, the DEO’s office would have to send an email to the specific gram panchayat to verify a birth certificate of a voter. Adrija had to check for these confirmations.

.webp)

“One time, the office wrote back saying that the identity paper was probably issued from their office, but they could not verify because a fire burned down their registers. I did not know what to do then, she said.

While speaking with us, she kept at her job. In another case, she lifted a sentence from her set of options and pasted it into the ECI software, “BLO Undertaking required linkage is not established”. A desktop operator, she was forced to act like a DEO.

When our reporter asked if these notes had been given as such from the magistrate to her, she replied, “We don’t get written checklists. Instructions are updated in meetings, and my colleagues and I discuss and make our script or standard operating procedure, which I write in my notes.”

For the district, we surveyed the ERO and their teams’ internally prescribed instructions and methods changed from one assembly constituency to another. How the District Magistrate was working in collaboration with ERO had also changed, even between neighbouring assembly constituencies.

In one constituency that we reported from, the electoral officer was also considering Pan Card, Ration Card and Death Certificates as sufficient documents for cases of logical discrepancies.

“For unmapped voters, we are strictly following ECI’s checklists that the voter must provide one of the 12 SIR documents to us. But we are being lax about logical discrepancies. These are voters who have already been mapped, so we are willing to be more lax. If they can give a document, which is otherwise not on the SIR list, to establish mapping linkage, we are considering it,” he told us.

When asked how the documents were being cleared by the DEO in their case, he replied, “The District Magistrate has given clear instructions to data entry operators here to just check the authenticity of documents, they are not to adjudicate on our basis of verification.”

On ERONET, while uploading documents, the officer can only upload them under the 12 options of the initial documents okayed by ECI. No toggle exists to upload other documents not specified by ECI, so these unlisted documents are uploaded onto the system under the wrong category.

“We are working with the DM office to speedily clear the logical discrepancies bottleneck. We decided to get the documents online, even if it is under the wrong category,” one ERO said.

“The DM has given instructions to his operators to check authenticity and links and not flag this otherwise, so this is our approach.” Again, no written instructions instituting these changes existed for this process at the ECI’s state office or even at the district level.

Another ERO from a neighbourhood constituency, we saw, was using PAN cards to clear logical discrepancies. In his case, he was not uploading them to ERONET. He was keeping them in a physical file for his own assurance. “The DM is clearing his docket fast here, just checking the authenticity of documents we upload, nothing else,” he said.

All the state officials had been forced by the ECI to operate blind. The bureaucracy lives and survives by rules and procedure. Paper trails of how they have ‘applied their mind’ to each case to follow the preset regulation create an auditable chain. In this case, they were being forced to imagine the procedure.

We learned that the district magistrates of at least three districts wrote to the West Bengal CEO’s office requesting clear instructions on their respective roles and procedural responsibilities.

Specifically, they asked whether they could accept documents beyond the standard thirteen for cases involving 'mapped' logical discrepancies. In doing so, they were essentially providing the West Bengal CEO with an opportunity to formally authorise the processes they were already deploying internally.

We reviewed a copy of one letter by the DM it said:

“Regarding logical discrepancies for mapped cases: An SOP may kindly be provided of logical discrepancy cases…and the role of BLO, ERO/AERO and DEO. Also, instruction may be provided about requisite documents to be taken at the time of hearing by ERO/AERO for such cases. It may be kindly noted that there is no provision for uploading other than 12 categories at the portal at the moment,” said the letter to the CEO.

Having received no response from the ECI, they continued with their internal methods regardless.

One ERO pointed towards other ways in which ECI’s software was steering the process.

“When hearings were first instituted, we received oral instructions from the West Bengal CEO that even though Aadhaar remains one of the 12 permissible documents for the SIR, an unmapped elector must submit an additional document from that list to be cleared,” he said.

“While this contradicts the original SIR instructions, we received no written orders. Just the software stopped allowing us (EROs) to only upload Aadhar. We were required by design to upload additional documents. The feature seemed to have disappeared now,” he said while showing us the interface. The Collective could not independently verify this claim.

Take another instance. For exceptional cases, particularly for older voters or sex workers for whom it would be impossible to have the 12 specified documents, ECI allows for a special clarification or enquiry instituted by the ERO to vouch for their inclusion. But the ECI’s software did not provide an option to upload the paperwork for these special procedures.

The ERO demonstrated it to us on the software interface. “ECI’s mandate is that no eligible voter should be left behind. But ECI’s own software does not allow this,” he said.

The Beginning, Or The End

On February 4, the West Bengal Chief Minister Mamta Banerjee appeared personally before the Supreme Court in her case against the ECI.

The Supreme Court has given notice to the ECI on her petition. The West Bengal elections are slated for April 2026. The voter rolls, therefore, have to be locked and ready by the end of February.

While final rolls are slated for publishing on February 14, the CEO West Bengal has asked ECI for a week's extension to this deadline.

The Supreme Court has to decide if what ECI has done in West Bengal will get its stamp of approval. Will ECI get to do “as it may deem fit” with the entire country’s voting rights?

We are attaching the compendium of all written orders issued by ECI to West Bengal Election Officials here.

.avif)