“Under the leadership of Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi, we are determined to eliminate Naxalism from its roots, and India is set to be Naxal-free by March 31, 2026.”

“Our security forces completed the biggest-ever anti-Naxal operation in just 21 days, and there were no casualties of the security forces in the operation.”

- Home Minister Amit Shah on May 14, 2025.

Bijapur, Chhattisgarh: First came the stench. A putrid smell hung around the Bijapur district hospital mortuary. Inside, bodies lay stacked one on top of another inside aluminium racks. They were bloated and rotting in the severe May heat in the absence of a freezer.

Men and women, breathing shallowly through the tightly tied scarves around their faces, moved to open each bloodstained body bag in the rack to look for faces of their relatives. Even those who had braced themselves for what they might find, recoiled after opening a bag: the body of a young woman, crawling with maggots.

“I couldn’t recognise the body of my sister,” said Joga (name changed) from Todka village in Bijapur. “She joined the Maoists when she was 17. Now she’s 22... and no more.” He turned to his parents and younger sister for counsel. Ultimately, they walked away silently, without claiming a body.

On May 14, officials in Bijapur announced the end of “Operation Karregutta” — a 21-day offensive against Maoist insurgents in the Karregutta hills in Chhattisgarh-Telangana border that began on April 21. They counted 31 Maoists dead, including 16 women.

According to the official press statement, ‘‘a large scale joint operation’’ in the 60-km stretch of forested hills was launched by Chhattisgarh police, including the District Reserve Guard (DRG), Special Task Force (STF) and Bastar Fighters as well as the CRPF, including COBRA commandos, ‘‘to weaken the armed strength of the Maoists, neutralise their armed groups, clear them from these difficult terrains, and dismantle the PLGA Battalion’’.

In the campaign, the security forces destroyed “216 Maoist hideouts and bunkers and defused 450 improvised explosive devices (IEDs), recovered 818 shells used in barrel grenade launchers, 899 bundles of detonating cords, detonators and large quantities of explosives’’.

At the heart of the story is a costly misfire. Claimed as “the largest and the most extensive anti-Maoist offensive in recent history”, the operation was meant to deliver a decisive blow to insurgency leadership. But the state had very little to display for its show of force: no senior Maoist leaders were captured or killed despite the offensive reportedly aiming at neutralising senior members of the Maoist central committee allegedly taking shelter in the Karregutta range. And it hides the disproportionately high human cost borne by tribal communities caught in the crossfire, further deepening the chasm between the State and its most marginalised citizens.

In response to a question in the press meet whether the stated objective of getting senior Maoists through this operation could be achieved, the director general of police Chhattisgarh responded that the forces ‘‘have achieved more than what they set out to’’ and ‘‘this operation marks the end of Naxal violence in the country as scheduled by March 2026.’’

It was a week after the end of operation Karregutta — an exercise that saw chopper rotorblades and explosive thunderclaps reverberate across the thick forest for days without a major trophy — that the government managed to reclaim its narrative with what it called a ‘real victory.’

This came not in Karregutta, but several kilometres away, deep in the Abujhmaad forests between Narayanpur and Bijapur districts, where Nambala Keshav Rao, the General Secretary of banned Communist Party of India (Maoist), and 26 other Maoists were gunned down in what became one of the most significant encounters in recent times.

Operation Amid the Fog

As India launched a military retaliation against Pakistan on May 7 in response to the Pahalgam terror attack, another war was well underway in a remote corner of the country in Karregutta hills against its own citizens who had taken up arms against the state.

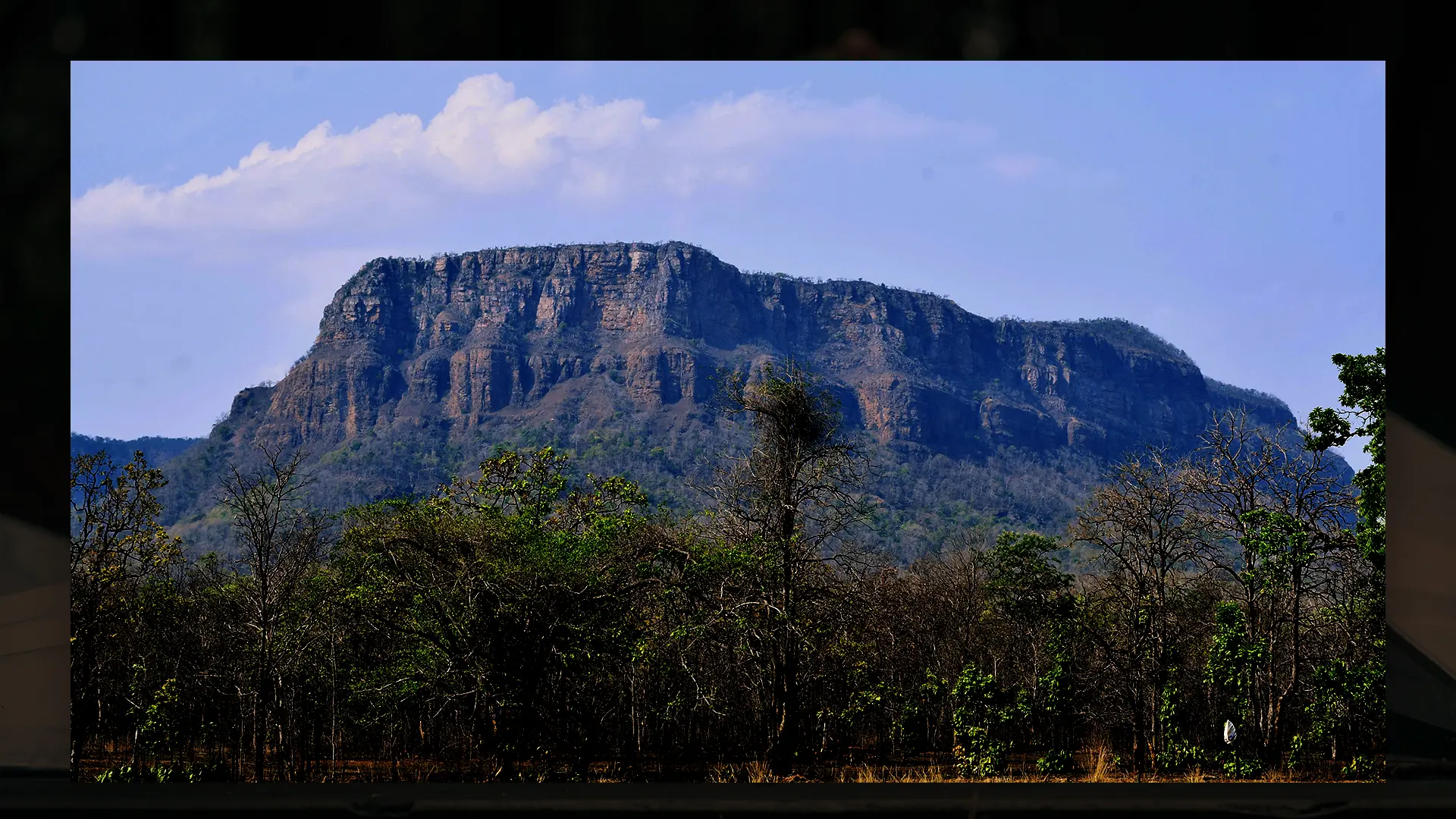

Villagers describe the Karregutta range as a network of over 200 hills, many interlinked by natural cave systems leading to adjacent peaks and nearby settlements. Beyond their striking landscape, the hills are vital to both economic survival and spiritual life. Karregutta hills have also served the Maoists as a strategic location away from the radar of security forces.

‘‘Operation Sankalp’’, a codename announced by the media, but denied by the government later, began in silence. As the paramilitary forces were rushed to the foot of the Karregutta hills, the only consistent flow of information came from media reports heavily reliant on unnamed sources.

And they set the narrative. Some reports spoke of 20,000 troops, others of 5,000, some reported on the involvement of elite units such as the Greyhounds of Telangana, and the C-60 force of Maharashtra.

When contacted by this reporter, the Superintendent of Police of Telangana’s Mulugu district categorically denied any involvement of the state police in the operation. “This operation is being conducted exclusively by the CRPF, including the COBRA battalion, and Chhattisgarh State Police. No other state forces are involved,” he stated.

Estimates of Maoist fighters “trapped” in the hills varied wildly: 150, 300, 500. Each number is more speculative than the last.

Across both regional and national outlets, details about the operation, including the number and type of forces deployed, the strategic depth of the mission, and the Maoist leadership allegedly “trapped” in the hills were consistently attributed to anonymous “senior officials.”

A significant portion of the coverage focused on speculation over the presence of top Maoist leaders such as Hidma, Sujata, Dewa, Damodar and Chandranna. Yet not a single top commander was arrested or confirmed dead.

In a press briefing held in Bijapur on May 14, senior officials from the police and paramilitary forces declared as concluded ‘‘the largest and most extensive anti-Maoist operation’’ to date. Present at the meet were Arun Dev Gautam, the Director General of Police (DGP), Chhattisgarh, and G P Singh, the Director General, CRPF, who described the campaign as ‘‘an effort to weaken the armed strength of the Maoists, neutralise their groups, clear them from difficult terrains, and dismantle the PLGA Battalion.’’

Union Home Minister Amit Shah declared it a resounding success and set a deadline of March next year to wipe out the Left-wing insurgency that has ranged for more than four decades in the country.

The operation spotlighted a security doctrine that’s gaining currency in India: the more hidden a war, the more easily it can be declared won.

31 Dead

Well before the official press briefing, people from the villages closer to the hills had started gathering at the Bijapur district hospital after hearing that their kin were among the dead in the security operations.

They came on May 9 in tractors and motorcycles, hoping to identify their sons, daughters, and siblings and take back the remains to give a decent burial.

“We got a call from police personnel working with the District Reserve Guard (DRG) on May 9, asking us to collect the bodies of three persons from our village,” said a young man from Hiroli, covering his nose and mouth with a scarf.

It was around 4 in the evening, and the stench was overwhelming. The DRGs are local recruits into the Chhattisgarh police, several of whom were earlier with the Maoists.

The mortuary sat close to the Women and Child Healthcare Unit. The stench from the rotting bodies forced pregnant women and parents with infants to flee the area. A mortuary staffer, standing at a distance, told families to pull open the steel racks themselves and identify the bodies.

Identification was tough because bodies don’t take kindly to time. Some were bloated, with post-mortem cuts splitting open at the seams under heat and decay. One particularly harrowing discovery left everyone speechless—a young woman’s body, covered in maggots, the shape of her chest the only clue to her gender and age.

Exhausted and overwhelmed, the villagers backed away.

“Aisa kaise le jayenge? (How can we take the bodies back in this condition?),” the young man muttered.

They had been given specific body numbers but not all matched. “We received a call from DRG personnel on the evening of May 7 saying our relatives had been killed in an encounter,” said Kosa Tamo, younger brother of the deceased Somdi Tamo, who along with the family of Motu Mudam, rushed from their village Kondapalli, over 60 km away in a tractor to the hospital the next morning, hoping for a prompt handover. Instead, they were told the postmortems weren’t complete. At the police station, they were turned away as the Station House Officer (SHO) was reportedly “not in town.”

Despite their limited resources, the families returned after five days upon receiving another call from the police to collect the bodies. This time, they were led through a detailed identification process: shown photos of deceased Maoists and asked to confirm the identity, followed by Aadhaar verification and body tag allocation.

But even this process was riddled with distress.

The Young Dead

“I identified the photo of my sister Manjula Karam,” said Mangal Karam from Hiroli. But the body tagged as hers—number 11—was so severely decomposed that it was impossible to tell if it was his sister. “We brought home a maggot-infested corpse. I don't know if it was my sister or someone else,” he said.

In another instance, Adme Punem, an elderly woman from Bhusapur, gulped a red energy drink before entering the police station to view the image of her son, Podia Punem—listed by police as a divisional committee member of the CPI (Maoist) with an Rs 8-lakh bounty. Accompanied by her nephew, she was told to collect body number 23. Twenty-three-year-old Podia, was with the Maoist party for five years, acknowledged the family.

But the body wasn’t there in Bijapur hospital. The family kept opening bodybags after bodybags, shaking their heads in denial each time.

After a flurry of calls between the police and hospital staff, they learned the body had been sent to Bhairamgarh Hospital, 45 km away, for postmortem. Adme had arrived on a tractor with another group. Her younger relatives were on motorcycles—none suited to transport a corpse.

The private ambulance service refused her. “We don’t provide ambulances for Maoists,” the driver reportedly said.

Only after heated arguments between the police and activists Soni Sori and Bela Bhatia was an ambulance arranged from Bhairamgarh. Around 1 am on May 13, Adme finally took her son’s maggot-ridden body home.

The official list containing the details of the dead Maoists revealed that most of them were young adults, showing the Union government clearly missed its mark.

Details of the dead insurgents released record the oldest cadre as 37. Among the dead were two divisional committee members, one Telangana state committee member, and a 27-year-old from the medical team. The remaining 28 were platoon and party members, with three still unidentified at the time of the briefing. The age of seven cadres is recorded to be above 30 while the rest twenty-four as 25 years and below; three of whom were 20 or younger.

One of them, Motu Mudam, was only 15 years old according to his parents who had come to collect his body. But he was listed as 19 with an 8-lakh bounty in the official list. According to his parents, he had joined the Maoist party six months earlier.

Similarly, in the list, Bhime Kunjam from Tumrel village was 20 years old with Rs 5 lakh bounty on her head. Her father Budra said she was only 16 and had run away from home to escape a marriage.

For some, the call to protect their forests threatened by government acquisition was a compelling reason to pick up guns, while others were coerced and compelled.

In my earlier interactions, families often had a tone of regret, with many vowing not to let their remaining children follow the same path and instead carry out overground resistance to safeguard their forest, land and water.

The Chief Minister’s assertion on his Instagram handle that Bastar is “writing a new chapter of peace, trust, and development” would ring hollow to those carrying home the decomposed bodies of their loved ones.

Disinformation and Denials

In the absence of verifiable information, the Karregutta operation opened the door for disinformation, body count claims, and political speculation.

On May 7, Chhattisgarh’s Chief Minister Vishnu Deo Sai publicly confirmed the death of 22 Maoists soon after a report of a major encounter. Hours later, deputy Chief Minister Vijay Sharma, who also holds the Home Affairs portfolio, contradicted him entirely, stating there was no such operation named Sankalp, and accusing the press of spreading “misleading information."

“I wonder where this information is flowing from,” Sharma said. “Let me tell you clearly: there is no such operation as ‘Operation Sankalp’. This is misleading news being circulated in the media.” He further added that the claim of 22 Maoists being killed was "completely untrue", asserting instead that the Karregutta operation was “like any other routine anti-Naxal operation.”

Chhattisgarh Pradesh Congress Committee president Deepak Baij addressed a press conference soon after, expressing concern over the apparent communication breakdown at the highest levels of the state government. Citing his own sources, Baij claimed that 22 bodies were indeed brought to Bijapur, and questioned both the Home Minister’s denial and the police’s silence. “Why is the government withholding the truth? And why is the Home Minister contradicting his own chief minister?” Baij asked.

What further worsened the confusion over the dead was the official list shared by the police on May 14 giving details of the 31 dead with names, position in the party, bounty on their heads along with photographs.

Over May 11 and 12, families from Hiroli, Todka, Palnar, Konjed, Busapara, Kondapalli, Tumrel, and Udtamalla arrived to claim 11 bodies, returned with seven, leaving behind four, either due to extreme decomposition or failure to identify. However, this reporter got phone calls from the village stating that the names of bodies they collected based on the information given by the DRG personnel did not match with the list shared by the police. If the names shared by the personnel (from the DRG unit) as having been killed in the operation are not listed in the final set of photos, then where are they? Are they still alive? Were they killed, with their bodies left uncollected somewhere in the forest?

“Bastar ke sangharsh grast kshetr me, buniyadi manveey garima ko aksar gambhir kshati pahunchti hai’ (In Bastar’s conflict-ridden region, basic human dignity is often hurt the most), said Soni Sori, a prominent Adivasi Activist from Bastar.

When young men and women leave their homes to join the Maoist movement, believed by many to be a struggle for jal, jungle, zameen, their families come to terms with the constant risk of death, she said. Yet, they continue to long for the chance to perform last rites, to bid farewell in accordance with their customs and lay their loved ones to rest among their ancestors. “Ab kya rahega unke paas, tuti hui yaaden aur chintajanak soch ki unhone kiske shav ka antim sanskar kiya”, ( What will they be left with now are the broken memories and the nagging worry over whose body they cremated) as she sent off Adme with her son’s body late in the night from Bhairamgarh.

“Handing over bodies in this manner is a complete violation of national and international laws that stipulate the State must preserve and dispose of the human body in a way that does not infringe on the right of the dead person to dignity in death and to a proper burial or cremation,” said Bela Bhatia, writer and human rights lawyer in Dantewada, who spent an entire day between police station and hospital helping people collect their dead relatives.

The Unsung

One of the consistent talking points of the Chhattisgarh government over the past two and a half years has been the low casualty rate among security personnel in its ongoing anti-Maoist operations. This narrative of “success with minimal loss” was tested during the 21-day-long operation, where ambiguous and often contradictory reports emerged on the health and injuries sustained by security forces.

Injuries from IEDs laid by Maoist cadres were dismissed as minor in official statements.

The first formal acknowledgement came only on May 6, when a police press release stated that “some personnel from COBRA, STF, and DRG were injured” during the operation—though the number of injured remained unspecified and their condition was again described as stable.

What was left out, however, was telling. For instance, there was no mention in the statement of the COBRA jawan who stepped on an IED and had to be airlifted to AIIMS Delhi on May 4 where doctors amputated his leg. Nor was there any reference to a series of media reports detailing multiple injuries to STF and DRG personnel in the same period.

It was only during the May 14 press conference, at the formal conclusion of the operation, that senior officials confirmed that 18 personnel—from COBRA, STF, and DRG—were injured, mostly due to IED blasts. The statement emphasised that all were “now out of danger and receiving the best treatment.” When asked by a journalist on the nature of injuries suffered by the 18 jawans, the DGP Chhattisgarh said: “……it would not be proper on my part to get into the details of the injuries.”

Land Mines and Maimed Bodies

The Karregutta hills lie within the Bhopalpatnam Granulite Belt (BGB)—a geological formation stretching over 300 km in length and up to 40 km in width. The hills divide Bijapur district of Chhattisgarh and Mulugu district of Telangana states. Comprising limestone-rich sedimentary rocks, this belt is known to contain valuable minerals and gemstones, including garnet and corundum, which add to the region’s natural wealth. Fossil records discovered here include those of reptiles and dinosaurs, including flying species, offering a remarkable glimpse into prehistoric life and Earth's evolutionary timeline.

Beyond geology, the hills have deep cultural and spiritual significance. Generations of Adivasi communities have settled along the foothills, forging lives intertwined with the forest.

But this lifeline of faith and sustenance has been scarred by the intensified conflict. Several villagers now live with amputated limbs, injuries, and trauma, their futures clouded by violence and insecurity.

These hills are our lifeline,” said Surya, a resident of Laxmipuram, Mulugu district in Telangana. From tendu leaf collection in scorching summers to bamboo harvesting post-monsoon, the forests provide seasonal income that carries many families through the year. The foothills also yield everyday nutrition—bamboo shoots and forest produce.

For others like Darra Sunita of VRK Puram in Telangana, from the Vadabalija backward caste community, the hills are sacred. Each May, villagers trek to the Bedam Mallana temple for annual rituals. Nearly every peak has a deity, anchoring cultural fairs that bind communities to their land.

On June 13, 2024, 32-year-old Sunita Darra joined 130 others from her village on the annual pilgrimage to the Bedam Mallana temple atop Karregutta hills. For the mother of two, it was a long-awaited pilgrimage. “I had only visited the temple once before my wedding,” she said.

Somewhere along the steep trail, Sunita stepped on a Maoist-planted IED—an explosive meant to deter security forces. Her left foot was blown off.

Her husband carried her, bleeding and semi-conscious, 10 km downhill to the nearest village. “Each step was terrifying,” said a neighbour. By the time they reached Pamunuru, it was dark. She was rushed to a local health centre and then to Bhadrachalam hospital, where doctors amputated her foot up to the ankle.

Faith overrules danger, as they say. Despite the tragedy, about 30 villagers went on a pilgrimage this year. Scared, the villagers restricted themselves to 30 pilgrims. “Luckily, there was no blast,” said a neighbour. “The goddess protected us,” she said, folding her hand and raising her eyes to the sky.

But for Boggalu Naveen, another Koya Adivasi from Anakanagudem village, there was no divine reprieve. On January 5 this year, while collecting bamboo near Veerbhadrapuram gutta, part of the same Karregutta range, he was injured in a similar IED explosion.

“I was the last in line. I heard a blast and collapsed,” said Naveen, who now limps, with black shrapnel spots still visible on his leg. His other friends carried him back, fearing death hiding under the ground. After a month in Bhadrachalam hospital, doctors advised six months of rest. “This season’s work is gone,” he said. A mason by trade, Naveen is now dependent on the Rs 25,000 he received from the Tribal Relief Fund. The promised Rs 3 lakh remains stuck in bureaucratic delays.

Two months after Naveen’s injury, Bogulla Krishna from the same village followed the same treacherous path in search of bamboo. With a wife and three daughters to support, the economic needs overruled the lurking risks. Krishna made the 10-km trek along with three others from the village. The bamboo from that part of the hill fetched good prices, and the season was closing. They needed to collect and weave before the monsoon.

He too stepped on an IED and lost his left leg completely.

According to official data from the Superintendent of Police's office in Mulugu, six people have been injured in the past two years - four in 2024 and two in 2025 - and three died in the blast.

But the official numbers may not tell the full story. In a nearby hamlet, a teenage boy who survived a similar blast now lives in hiding with a cousin, unwilling to speak. “He fears both sides,” says a woman preparing for a family wedding. “If the police find out, he’s scared of being picked up. If the Maoists hear he has spoken, he fears retaliation.” “Are there many like you?’ this reporter asked, he simply shrugged.

Maoists Warning

Two weeks before the Karregutta operation began, a Maoist note in Telugu circulated on WhatsApp groups warning that they have set up explosives “to protect ourselves”. The note further stated that the party had warned people about these explosives in several ways, however tricked by the police to get atop the hills, many tribals and non-tribals are falling victims to the explosives by falling into the monetary trap laid by the police, “We appeal to the public not to fall into their trap and come to Karregutta,” ended the note signed by Shanta, secretary, Venkatapura-Vajidu Area Committee of Maoist Party.

But the formal warning came too late and with a price. Not only many had lost lives and limbs, but two weeks later the hills were surrounded by central paramilitary forces both from the Telangana and Chhattisgarh sides.

Thus began the 21-day operation in the Karregutta hills.

Conclusion

The Karregutta operation was launched even as Maoists issued six letters over four months with offers to talk peace, starting March 28. These letters, including the latest one of July 1 appealing to the Congress government in Telangana, appealed to declare ceasefire to enable talks. The note welcomed the statement made by Telangana Congress President Mahesh Kumar Gaud for condemning Home Minister Amit Shah’s refusal to engage with its Adivasi citizens, yet enter into a ceasefire with Pakistan.

But both the Chhattisgarh and Union governments have demanded that Maoists lay down arms, and have refused to ease operations. In the last 18 months, over 415 alleged Maoists, mostly young Adivasis, and 39 security personnel, many from the same communities, have been killed. Several civilians, too, have been targeted by Maoists in Bastar for allegedly aiding the police — 22 were killed this year and 71 the previous year.

.avif)