Destination India: Illegal Gold Laundered Clean by the Ghana Government

In September 2025, Ghana Gold Board, commonly known as GoldBod, issued a bounty of $90,000 on the head of an Indian gold trader, Muhammed Afsal Puthalan. GoldBod is Ghana’s newly formed state authority, aimed at centralising the trade and export of the country’s gold.

Puthalan, hailing from Thrissur, Kerala, was involved in the largest gold smuggling syndicate that GoldBod claimed to have busted since its establishment in March 2025. Puthalan’s firm, RAFMOH Gold Private Limited, had traded in 100kgs of gold illegally purchased from the Ghanaian black market, GoldBod claimed.

In the past few months, this newly formed Ghanaian authority has made several arrests to curb the trade of illegal gold. It claims to combat illegal gold mining, which is growing rampant in Ghana. Several Indians, not just Puthalan have been caught in the fray of its widely publicised arrests.

But, these publicly exposed cases hide a larger trade: that of gold, washed clean of its illegality by the Ghanaian government and sold to traders worldwide, including Indians.

On September 10, Ghanaian President John Dramani Mahama announced that the state authority would not distinguish between gold mined legally and illegally. GoldBod would sell it all, washing off its illegality.

This allowed the Ghanaian government to benefit from the rapidly proliferating illegal gold mines in the country. Traders from the rest of the world can now legally buy gold from which is otherwise procured illegally and unethically.

India, making up a sixth of Ghana's gold exports, stood to gain. Indian customers do not demand ethically-sourced gold. The risks of buying gold from Ghana were now much lower.

Forbidden Stories, in collaboration with The Reporters’ Collective and The Fourth Estate, investigated the steep price Ghana pays for its government's trade in tainted gold—a practice that benefits traders and consumers worldwide, including in India.

Poisoned Waterways, Destroyed Forests and Journalists Under Attack

Under repeated assaults from hundreds of excavators and artisanal miners, the Offin River is now a shadow of its former self.

This major waterway, a tributary of the Pra River, carries a muddy, yellowish flow that no longer reflects the sky. The mercury and arsenic dumped into it every day are residues of mining activity as well as sediments stirred up by the diggers, which have destroyed its clarity.

Not only do the rivers suffer, but so do nearby forests and plantations, razed by excavators. The damage is so severe that President Mahama, elected in December 2024, is being pressured to declare illegal gold mining a “national emergency.” His government is stepping up media initiatives to combat the practice, known locally as galamsey, a contraction of “gather and sell.”

Erastus Asare Donkor, a reporter for the 24-hour news channel JoyNews and a figure in Ghanaian journalism, has been a victim of the rise in organised crime. On Oct. 20, 2024, during a shoot at an illegal mine located in the heart of a forest reserve, he and his crew were beaten by a group of heavily armed men, who forced them to delete their footage. “I thought they were going to kill us,” he told Forbidden Stories, still visibly shaken. A trial is underway against four of his attackers.

Although galamsey is nothing new in Ghana, its scale has grown in recent years. “Way back in the first term of the current president, in 2014, this illegal mining business started expanding… And then from 2016, when power changed hands, we saw the influx of more Chinese nationals who brought in equipment and money,” Donkor said. In response to this phenomenon, the government has stepped up its initiatives: measures deemed by its critics to be too symbolic or too isolated in nature to be truly effective.

Galamsey has become an extremely dangerous subject for journalists in Ghana to cover. Since October 2024, about 10 journalists and their teams have suffered abductions, beatings or death threats during their reporting. Forbidden Stories, whose mission is to continue the work of silenced journalists, visited the region in partnership with The Fourth Estate, a nonprofit investigative media outlet.

The risks faced by journalists are commensurate with the rivers of money generated by this business. Ghana is the largest gold producer in Africa and the sixth-largest worldwide. In 2024, gold represented 57% of the country’s merchandise exports, worth nearly 11.47 billion dollars. But this official figure is far from reality. The Swiss NGO Swissaid calculated that the quantity of gold exported in 2021 from Ghana to the United Arab Emirates alone was 10 times higher than the officially declared amount. According to Swissaid, 229 tons of gold, worth nearly 11 billion dollars, were smuggled out of Ghana between 2019 and 2023.

It’s more than enough to lure fortune seekers, seduced by TikTok videos of miners boasting about their supposed wealth and proudly displaying their weapons. Amid this mad rush for profit, it was only by being escorted by armed guards and taking multiple precautions that Forbidden Stories was able to report on ground in the month of July. There, gold refiners, buyers and producers disclosed their illegal practices, often on conditions of anonymity and away from prying eyes.

Journalists from Forbidden Stories, The Fourth Estate and The Reporters’ Collective managed to reconstruct an entire chain of illegal gold laundering, from the trenches of an artisanal mine in the Ashanti region all the way to India, passing through a slew of intermediaries. Despite numerous high-profile police operations, the gold fever shows no signs of abating. The price of gold has just broken new records on the markets, exceeding $4,000 — more than Rs 3.45 lakh — per ounce (28 grams).

Fully anonymous transactions

To understand how the gold that nearly cost Donkor his life, gets to its destination, one must travel several hours by dirt road from the large city of Kumasi and through a tropical forest scattered with craters dug by galamsey miners. The first link in the gold chain, a local buyer, is based in the small village of Dawusaso, the closest town to the illegal site in question. Along the road, gold has taken over everything, including some police posts adorned with advertisements for local refineries. It is not uncommon for totally illegal artisanal mines to spill over to the roadside, just a few dozen meters from officers on duty.

Upon arriving in Dawusaso, we met with John*, who has been living there for four years. Sitting behind his desk, in a sparsely furnished 10‑square‑meter room, he agreed to talk but forbade any filming. “Sometimes, the origin of the gold is not legitimate, so you don’t ask about it,” he said, explaining that he deals with “10 to 20 miners per week.”

During the conversation, two men entered the room. One of them wore large rubber boots caked with mud. Here, only artisanal miners bring their spoils to rural buyers, also called bush buyers. Industrial mine production goes through much more regulated channels. Without delay, they laid a gold nugget on John’s desk, which he weighed and offered them a price for. They accepted without a word, seizing the bundle of bills he handed them, and left. As John had described a few minutes earlier, the transaction took no more than a few minutes, with no questions asked and no documents exchanged.

How much artisanal gold enters the commercial circuit like John’s does, without any traceability? In the absence of reliable figures, Swissaid estimates that 30 to 50% of Ghana’s gold production comes from small artisanal operations like those John deals with. According to interviews that Forbidden Stories was able to conduct with actors in the sector, at least half of these operations are entirely illegal, meaning they do not have the necessary licenses from authorities.

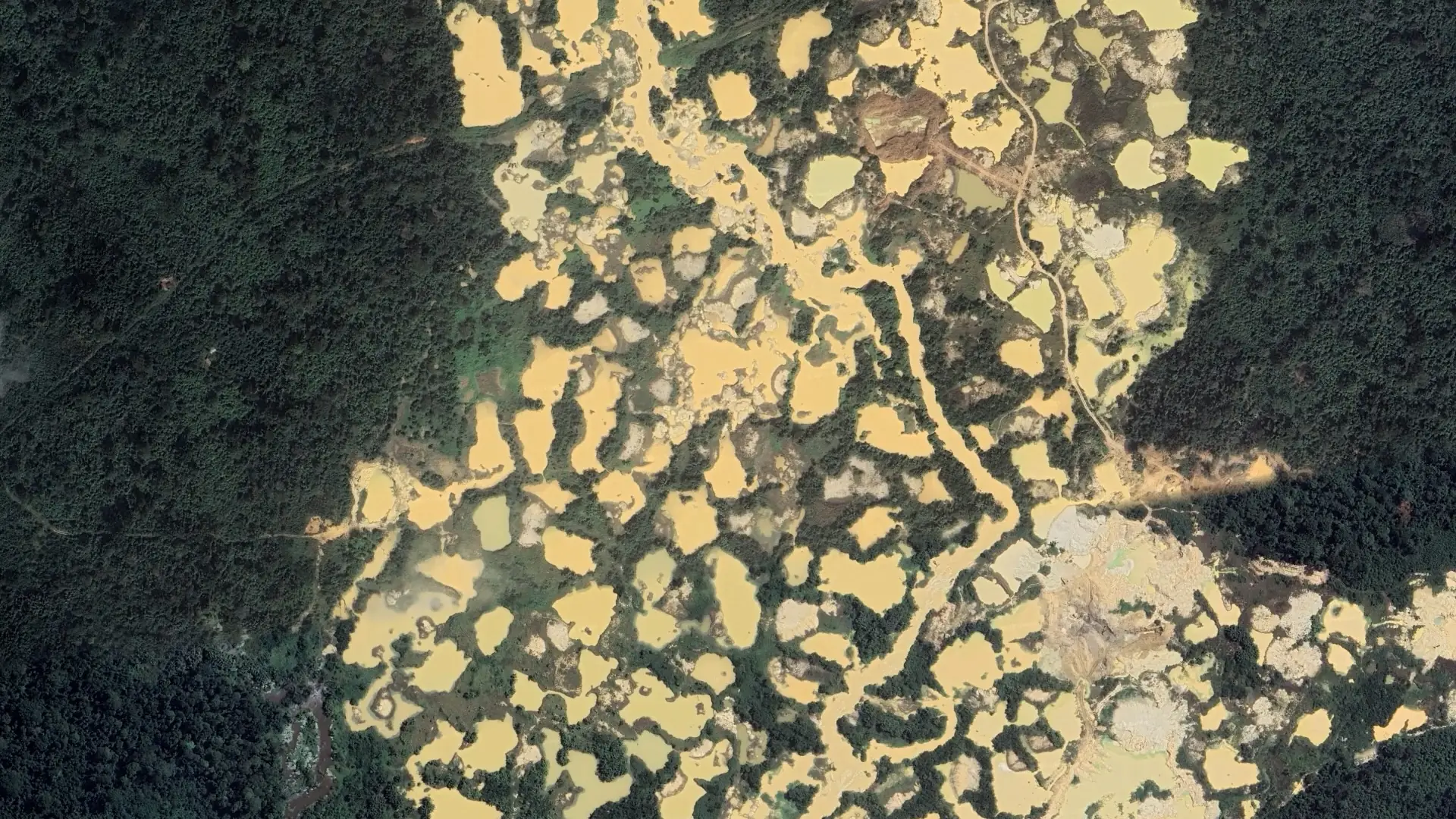

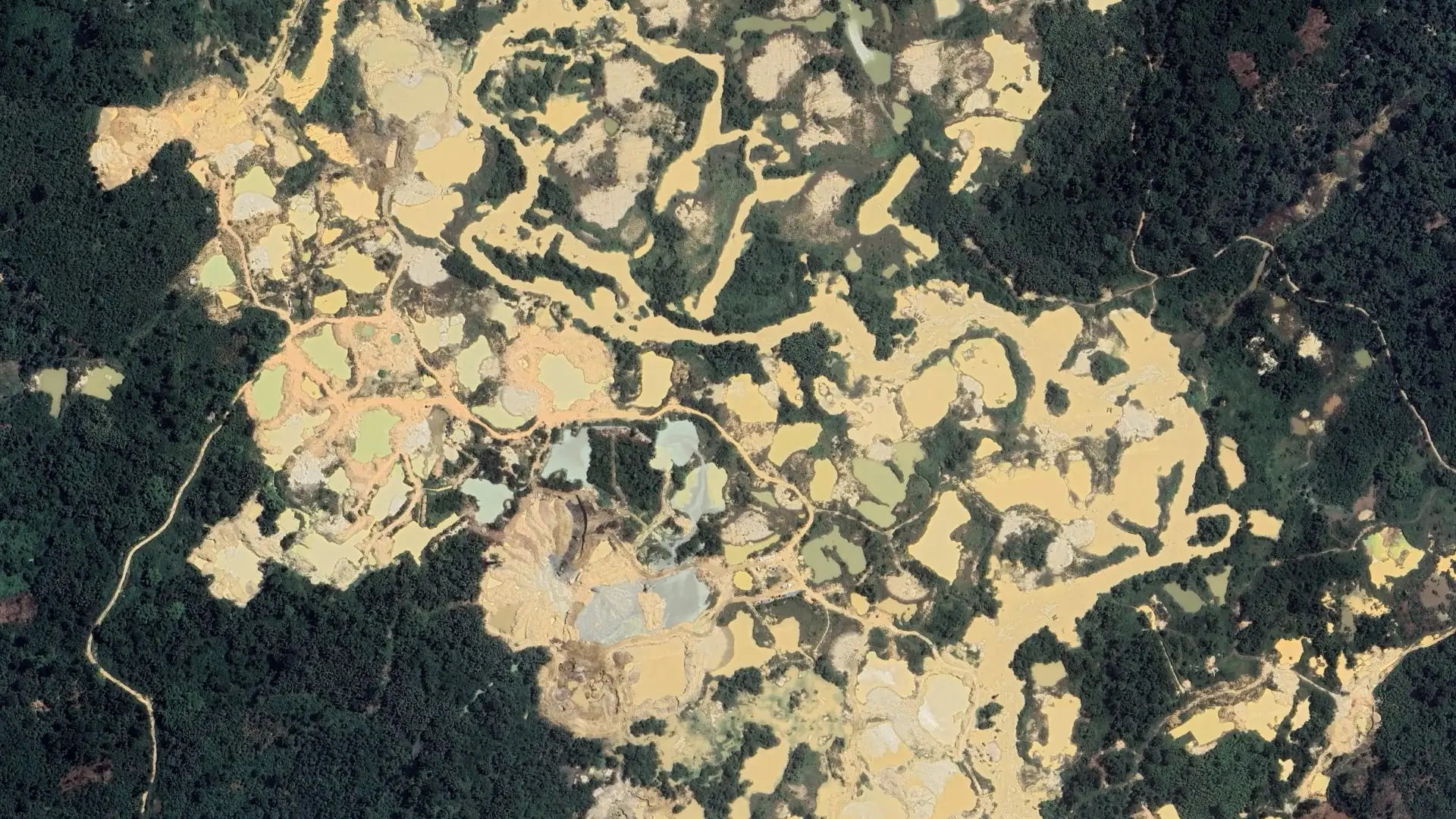

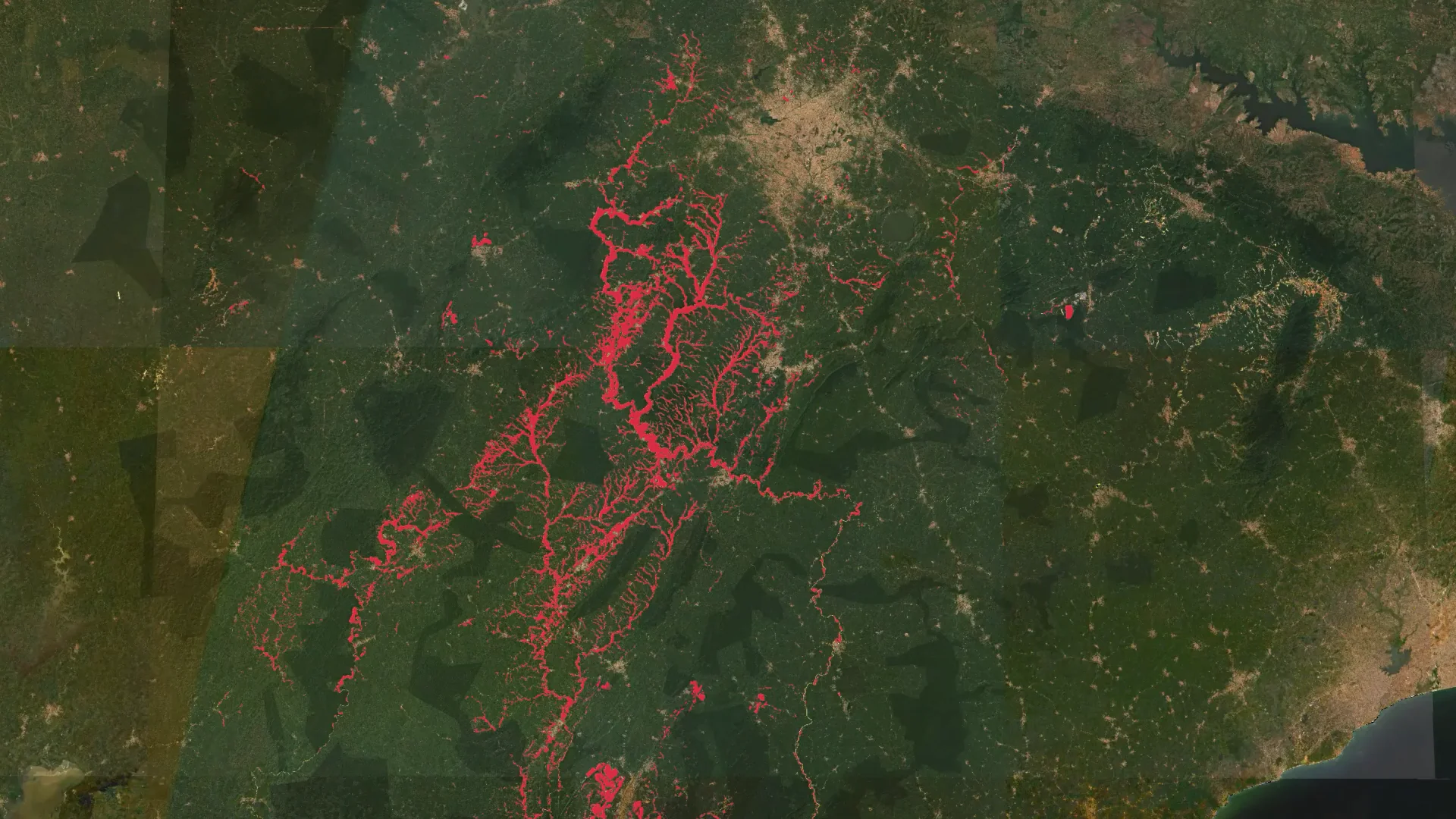

We sought to verify this information and assess the true extent of these illegal mines. We identified the land footprint left by mining operations in southwestern Ghana, the epicenter of the gold rush. Then we compared it to the GPS data from the Ghanaian government’s official mining concessions. Observing the territory from above, the results proved alarming: more than three-quarters of the identified past or present mining operations were found to be illegal. The devastation covers an area equivalent to twice the size of Indore. Forests, rivers, and wildlife have been destroyed in complete illegality.

We mapped nearly 150,000 hectares affected by active and abandoned mines in the region.

Some of these mines are located within protected areas.

77.4% of the identified mining operations lie outside the concessions granted by the state : they are illegal

Ghanaian President Makes Promises

Ghanaian President Mahama’s government is making numerous promises to retain foreign investors frightened by the explosion of criminal practices in the gold sector. Among them: the revision of license allocations, the centralization of exports via a new office, the GoldBod, and increased police operations. Faced with the extent of illegality revealed by our analysis, neither the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources nor GoldBod responded.

Between late March and early August, we recorded 26 police operations against illegal mines. In total, 306 arrests were made during these raids. In this context, the voices of legal artisanal miners struggle to be heard — something Michael Kwadwo Peprah knows all too well. “I ask every person who sells me gold where it comes from,” said Peprah, the head of an association of artisanal miners.

A few days before meeting with our reporters, the police arrested Peprah during an anti‑galamsey operation, accusing him of obstructing the arrest of illegal miners in the middle of a forest reserve. He criticises the authorities for acting too brutally, fearing “unauthorized seizures, with individuals impersonating security agents to extort money from miners.” Without being able to provide further details, Peprah hopes that Ghana will be able “to guarantee the traceability of gold through a software” that is due to be launched by the end of the year.

For now, police efforts do not seem to be making a dent, and for many professionals, Ghanaian gold still smells like trouble. “Are we seeing a meaningful appetite to actually engage with the rules set out by the London Bullion Market Association, OECD and the likes? We don’t think that the current administration is complying, so we’ve had to walk away,” said an expert from a large U.S. intermediary in gold purchase, speaking on condition of anonymity.

This view is shared by Alan*, who works as a consultant in the artisanal mining sector in Ghana. “If I told you that by the end of the year, or even next year, everything will be transformed, that would be a lie. It will take time. It will take effort,” he said.

Not everyone has the same reservations. Chinese nationals, for example, are regularly singled out because of their involvement in illegal gold production. But John, the buyer in the small village of Dawusaso, knows other key players in this clandestine business.

“I sell the gold to Indian traders in Kumasi. Not in a shop: in a house without any signs. They don’t ask me where the gold comes from… and I don’t know their names,” he said. On-site checks confirm that the location does indeed have equipment for refining gold. In Ghana, Kumasi has become a hub for the precious metal, which is bought there for cash before being redirected to the capital of Accra and then exported across the world — including Southeast Asia.

Indian traders, Ghanaian frontmen

For several Indian traders the method is simple: they buy at a higher price than on the legal market. Kofi*, an unlicensed buyer in the region, estimates that the price difference is nearly 20%, or about Rs 14 lakh for a kilogram of gold. For discretion, our reporters met him in his car, on a vacant lot in the suburbs of Kumasi. “On the black market, you can sell to the Chinese traders or to the Indian traders. You schedule a meeting over the phone and meet them directly in their homes,” said Kofi, who claims to buy and resell 15 kg of gold per year — the equivalent of Rs 16.9 crore in value.

Since April 30, 2025, however, foreigners no longer have the right to buy or sell gold on the local market, in order to prevent gold from disappearing without benefiting the state’s coffers. But this new measure is easy to circumvent. “To keep up their business, if it’s a company buying the gold, they’ll put a Ghanaian in front, so as to keep operating,” explained Kodjo*, who owns a legal gold mine in the region and has worked in the sector for three decades.

One example is the company Unique MM, which experienced a highly publicized police raid in late April. Indian traders had been hiding behind a Ghanaian frontman, according to authorities, and the gold purchased from artisanal mines in Kumasi was being illegally shipped to India. Unique MM did not respond to our questions.

India has also been involved in another gold‑trafficking case that made headlines in Ghana recently. This time, it was an Indian company that the authorities caught in their nets. Suspected of having bought 100 kg of gold on the black market in two months, from a Ghanaian intermediary in the country’s southwestern mining basin, the company was severely punished. Its jewelry shop in the capital of Accra was immediately closed, and its directors and presumed associates were arrested or placed on a wanted list, with a hefty reward of Rs 71 lakh. The lawyers representing the company denied any wrongdoing but did not respond to our questions.

But these rare publicly exposed cases are unlikely to dry up artisanal gold production. Tons of that gold are exported completely legally by GoldBod, the new state authority that centralizes the country’s gold before export to counter trafficking — even if it means laundering gold from illegal mines. During a press conference on Sept. 10, President Mahama himself said that whether the gold was from legal or illegal sources, Ghana should “get the benefit of it.”

It’s worth the risk: between January and August 2025 alone, nearly 67 tons of artisanal gold, representing more than Rs 50.8 thousand crore, were shipped. Compare this to 63 tons of gold, equivalent to nearly Rs 40.6 thousand crore, from industrial mines.

India is the 6th largest importer of this increasingly sought-after metal. According to commercially available customs data that we reviewed, no fewer than 13 tons of gold departed from Ghana for the subcontinent between late May and mid‑August 2025. Eight of those tons passed through GoldBod. On some days, such as June 3, 2025, more than 600 kg of gold landed in India.

There was only one buyer for GoldBod: Sovereign Metals Limited, a company from India’s northwestern state of Gujarat, which purchased gold bars that were more than Rs 7000 crore. It’s a reflection of the country’s immense thirst for gold, which is prized both as a financial investment and in the form of jewelry for weddings or traditional ceremonies. By permitting the export of illegally mined gold through GoldBod, the Ghanaian government enables traders like Sovereign Metals Limited to acquire the precious metal, which has been effectively laundered of its illicit origins.

Sovereign Metals Limited, which reported revenues of nearly Rs 4986 crore in 2024, is part of a group of companies specialised in precious metals and offering refining, trading and jewelry manufacturing services.

“These are groups that try to control as much of the supply chain as possible, from importation to the sale of jewelry,” explained Marc Ummel from Swissaid. “In general, they sell imported gold mainly on the Indian market in the form of jewelry, and a small portion internationally,” he continued, citing the United Arab Emirates as a popular destination.

At the helm of this bling empire is the Indian Lodhiya family, a dynasty in the sector. The current CEO of Sovereign Metals Limited represents the fourth generation to trade in gold and silver. When asked about the precise origin and legality of the gold sent to India, GoldBod didn’t reply. Same silence from Sovereign Metals Limited, whose website claims “responsible sourcing and ethical business practices.”

*Names have been changed to protect the anonymity of those involved.

Support independent Journalism

The Reporters’ Collective collaboratively produces investigative journalism. In many languages and mediums. We report truthfully and bring out facts that the powerful prefer to keep hidden from citizens.

Besides courage and integrity, such reporting requires resources. We need your support. We need citizens to donate to keep us going and keep our work free to read for those who can’t afford to pay. Your donations will help us remain independent and work without fear.

You can change how much you give or cancel your contributions at any time.

By proceeding, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions. To find out what personal data we collect and how we use it, please visit our Privacy Policy.