We thought we had seen enough chaos, confusion, and absurdity while reporting on the Election Commission of India’s (ECI) revision of the Bihar voter list. That is, until our data analysts forwarded us another claim from the ECI to verify.

According to the ECI, two men, Vindheshwar Chaudhuri and Madhuresh Verma, residents of Sadhwra village in Keoti, have declared themselves non-Indian citizens and requested removal from Bihar’s voter roll. These two are part of a disaggregated list of over 200 people the ECI is processing to delete as alien citizens.

The details provided indicate that Chaudhuri and Verma are men aged above 40, who likely voted in Bihar as citizens in the past. The ECI claims they have now declared themselves aliens and requested removal from Bihar’s final voter list.

The ECI has mandated that during the Special Intensive Revision (SIR), its army of officials will verify each voter’s citizenship. Before the Supreme Court, on August 8, the ECI reasserted its right to verify citizenship for voting purposes.

Chaudhuri and Verma’s applications provided an opportunity to test the ECI’s capability to ascertain citizenship in this hasty process. Here’s what we found: Vindheshwar Chaudhuri and Madhuresh Verma are not alien citizens, contrary to the ECI’s records.

Both had submitted their documents when the ECI’s booth-level officers collected enumeration forms over 30 days in July, as confirmed by their relatives and neighbors. However, both passed away in August during the second phase of the SIR verification drive.

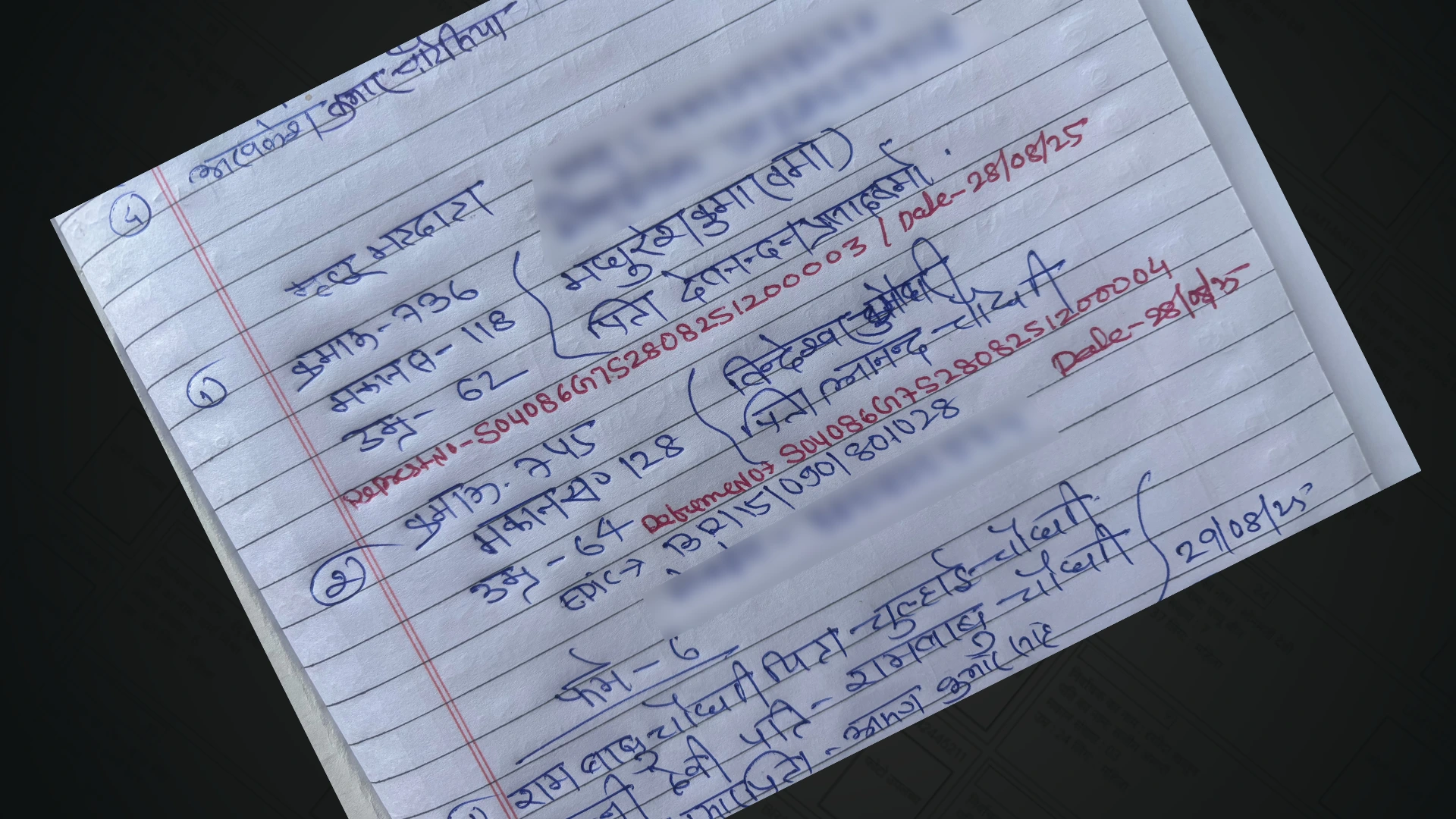

In both cases, the booth-level officer (BLO) noted their deaths during the verification process. Instead of the families filing for the deletion of their names from the voter list, the BLO took it upon himself to initiate the process. However, when filing the form for their removal, he mistakenly noted the reason for their exclusion as "not Indian citizens."

On the ECI’s records, two deceased men are now listed as having declared themselves aliens. This is the kind of information being aggregated for the ECI to later announce how many non-citizens it has weeded out.

Typically, a Form 7, which initiates deletion from a voter list, must carry the signature or consent of the individual filing it. A BLO initiating the removal of an individual must obtain consent from neighbours or relatives or use their own voting ID to file the form.

We spoke with the BLO, who claimed he had no idea how he had declared the two men as aliens. In desperation, he showed us his broken smartphone, its screen barely functional, and the ECI’s dashboard, meant to digitise the revision process, which wouldn’t open.

It’s easy to blame the BLO, but our reporting makes it clear that the blame lies with the ECI for ordering the re-registration of nearly 8 crore voters from scratch at an unprecedented speed. The haste was mandated from the top, and BLOs are merely the ECI’s last-mile messengers delivering the ensuing chaos.

Throughout our reporting on Bihar’s electoral rolls, we’ve learned that citizenship, and by extension a voter ID, holds special significance for citizens. Among all official identification documents provided by the state, a voter ID is colloquially called the “pehchan patra”—the one document that inextricably links individuals to the state, its welfare mechanisms, and their rights, especially in a state with significant poverty.

The fact that this identity was stripped from two individuals, even after their deaths, sparked outrage among Sadhwra’s residents. A local proprietor contacted Madhuresh Verma’s brother in Delhi, who was at a loss for words. “Tell me how this could have happened,” he asked us, imploring us to find the culprit. He wondered if Madhuresh’s predicament stemmed from old village rivalries or enemies resurfacing.

Vindheshwar’s widow was unaware that her husband had been removed in this manner. She said, “The booth-level officer visited again while we were conducting the last rites. I told him my husband was dead, and he went away.”

Both men’s exclusion requests have been forwarded to the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO), who, according to the ECI’s clarification to the Supreme Court, is the sole quasi-judicial authority tasked with adjudicating their citizenship.

Official slips will be sent to both Madhuresh’s and Vindheshwar’s addresses, summoning them to appear before the ERO. Both are deceased and cannot attend the hearing that will decide their citizenship status.

Madhuresh had no family left in Sadhwra; he had returned to the village after years in Delhi to rebuild his childhood home. Who will receive his summons? Would Vindheshwar’s widow know enough to appear before officials to fight for her husband’s case? She, like others in the village, including the BLO, was unaware they had been mistakenly marked as non-citizens.

During our reporting, we encountered several individuals who didn’t understand how to respond to the ECI’s summons or appear before the ERO, who decides on their inclusion or exclusion. Would Vindheshwar’s widow know what to do? Even their BLO, Mahesh Kumar, had no idea how to rectify this mistake. Would he be able to guide her correctly? If individuals are deceased, they must be removed from the voter list, but does the state care about the reason for their removal? Would the ERO uphold their citizenship if no one appears on Madhuresh and Vindheshwar’s behalf?

As of now, we don’t know.

Is this how ECI will eventually sum up and declare how many people it has removed as non-citizens? We all need to know. Because ECI’s template in Bihar voter roll revision is going to be replicated all over the country. The Reporters’ Collective continues to investigate.

The tax authorities have revoked our non-profit status claiming our journalism does not benefit the society. The order has severely choked the funds we need to carry out investigative journalism.

If you believe the government and the powerful in the country need to be held accountable to citizens. If you believe our journalism does so, please donate to keep the Collective alive. Now more than ever we need your support.